By Amr Saber Algarhi, Sheffield Hallam University and Konstantinos Lagos, Sheffield Hallam University | –

After 11 months of war, Israel is facing its biggest economic challenge in years. Data shows that Israel’s economy is experiencing the sharpest slowdown among the wealthiest countries of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD).

Its GDP contracted by 4.1% in the weeks after the October 7 Hamas-led attacks. And the downturn continued into 2024, falling by an additional 1.1% and 1.4% in the first two quarters.

This situation will not have been helped by a nationwide strike on September 1 that, albeit very briefly, brought the country’s economy to a standstill amid widespread public anger at the government’s handling of the war.

Amr Saber Algarhi & Konstantinos Lagos / OECD, CC BY-ND

Israel’s economic challenges, of course, pale in comparison to the complete destruction of the economy in Gaza. But the prolonged war is still hurting Israeli finances, business investments and consumer confidence.

Israel’s economy was growing fast before the start of the war, thanks largely to its technology sector. The country’s annual GDP per capita rose by 6.8% in 2021 and 4.8% in 2022, much more than in most western countries.

But things have since changed dramatically. In its July 2024 forecast, the Bank of Israel revised its growth predictions to 1.5% for 2024, down from the 2.8% it had predicted earlier in the year.

With the fighting in Gaza showing no sign of letting up, and the conflict with Hezbollah on the Lebanese border intensifying, the Bank of Israel has estimated that the war’s cost will reach US$67 billion by 2025. Even with a US$14.5 billion military aid package from the US, Israel’s finances may not be enough to cover these expenses.

This means that Israel will face tough choices about how to allocate its resources. It might, for instance, need to cut spending in some areas of the economy or take on more debt. More borrowing will make loan repayments larger and more costly to service in the future.

Israel’s deteriorating fiscal situation has prompted big credit rating agencies to downgrade the country’s status. Fitch lowered Israel’s credit score from A+ to A in August on the grounds that an increase in its military spending had contributed to a widening of the fiscal deficit to 7.8% of GDP in 2024, up from 4.1% the year before.

It could also potentially jeopardise Israel’s ability to maintain its current military strategy. This strategy, which involves sustained operations in Gaza aimed at destroying Hamas, requires boots on the ground, advanced weaponry and constant logistical support – all of which come at a great financial cost.

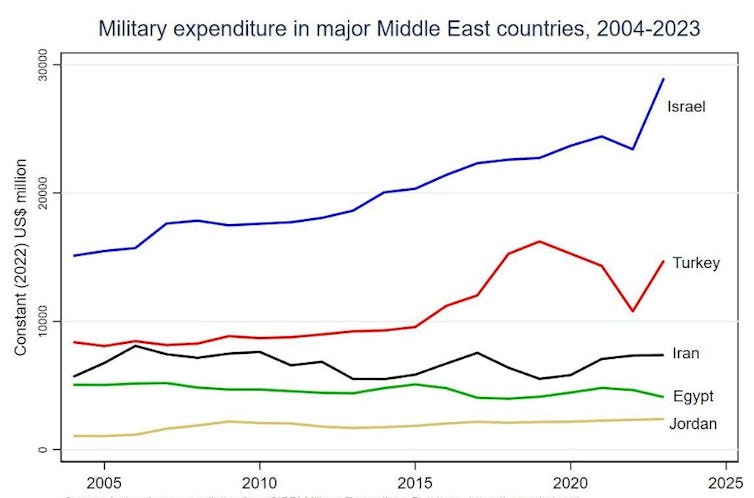

Amr Saber Alarhi & Konstantinos Lagos / SIPRI Military Expenditure Database, CC BY-NC-ND

Aside from macroeconomic indicators, the war has had a profound impact on specific sectors of Israel’s economy. The construction sector, for example, slowed down by nearly a third in the first two months of the war. And agriculture has taken a hit, too, with production down by a quarter in some areas.

Roughly 360,000 reservists were called up at the start of the war – though many have since returned home. More than 120,000 Israeli have been forced from their homes in border areas. And 140,000 Palestinian workers from the West Bank have not been allowed to enter Israel since the October 7 attacks.

The Israeli government has sought to fill the gap by bringing in workers from India and Sri Lanka. However, many key jobs are bound to remain unfilled.

It is estimated that up to 60,000 Israeli companies may have to close in 2024 due to staff shortages, supply chain disruptions and waning business confidence, while many companies are postponing new projects.

Tourism, although not a key part of Israel’s economy, has also been severely affected. Tourist numbers have dropped dramatically since the start of the war, with one in ten hotels across the country now facing the prospect of shutting down.

How this war affects the wider region

The war may have battered Israel’s economy. But the effect on the Palestinian economy has been far worse and will take years to repair.

Many Palestinians living in the West Bank have lost their jobs in Israel. And Israel’s decision to hold back most of the tax revenue it collects on behalf of Palestinians has left the Palestinian Authority strapped for cash.

Trade in Gaza has also ground to a halt, which means many Palestinians now rely on aid. While, at the same time, vital communication channels have been cut off and crucial infrastructure has been destroyed.

The effects of the war have stretched beyond just Israel and Palestine. In April, the International Monetary Fund said it expected growth in the Middle East to be “lacklustre” in 2024, at just 2.6%. It cited the uncertainty triggered by the war in Gaza and the threat of a full-blown regional conflict as the reason.

A flare-up in violence in Gaza has inflicted economic damage on an even wider scale than this before. Israel’s bombardment of Gaza in 2008, for example, pushed up the price of oil by nearly 8% and caused concern for markets all over the world.

Israel’s war in Gaza, which is fast approaching its first anniversary, is taking a heavy economic toll. Only a permanent ceasefire can repair the damage and pave the way for recovery in Israel, Palestine and the wider region.

Amr Saber Algarhi, Senior Lecturer in Economics, Sheffield Hallam University and Konstantinos Lagos, Senior Lecturer in Business and Economics, Sheffield Hallam University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved