By Grant Wilson, University of Birmingham; Daniel L. Donaldson, University of Birmingham; and Iain Staffell, Imperial College London | –

Great Britain’s electricity system (Northern Ireland is part of the integrated Irish electricity grid) made a leap forward in August 2024. The amount of power generated by fossil fuels fell to 3.6 terrawatt-hours (TWh), its lowest level in over a century. This meant that each kilowatt-hour of electricity consumed during August emitted on average just 84 grams of CO₂.

The record-low contribution of fossil fuels to British electricity in August will have affected household emissions. Heating your home with an average heat pump in August would have been eight times cleaner than using a gas boiler for instance, while charging a typical electric vehicle could have been about ten times cleaner than a petrol car.

Before August 2024, monthly generation from fossil fuels had never dipped below 4 TWh, even during the lockdowns of 2020 when demand for electricity and transport fuels plummeted. What’s more exciting is that this was the first time fossil fuels (98.5% gas and 1.5% coal) fell to third place in the British electricity mix over an entire month.

Gas power plants can be quickly and reliably ramped up when there is a surge in electrical demand or a lull in output from weather-dependent renewables like wind and solar. This makes phasing out gas particularly difficult. That’s why the results from August 2024 are so encouraging: gas appears to be losing its dominance.

While the contribution of gas to Britain’s electricity will rise again in autumn and winter, its meagre showing in a low-demand month like August suggests its heyday is waning.

What the data shows

August typically sees very low demand for electricity. There is next to no need for space heating, Britain still has low levels of air-conditioning and there is lower industrial and household demand while more people are away on holiday and fewer people are at work due to the month’s two bank holidays.

Lower demand means that less electricity needs to be generated or imported, and so a greater share of it can come from the installed capacity of low-carbon sources like wind, nuclear, solar and hydro.

However, lower electrical demand in Britain alone does not guarantee there will be lower generation from fossil fuels. For example, the power sector in August 2022 emitted 4.4 million tonnes of CO₂, whereas in 2024, this dropped to 1.7 million tonnes.

This was in part due to Britain being a net exporter of electricity (1 TWh) to the European continent in August 2022. Whereas this year, Britain was a net importer of 1.9 TWh. To put this in perspective, this 2.9 TWh change in net monthly trade is about 80% of the electricity generated from fossil fuels in August 2024.

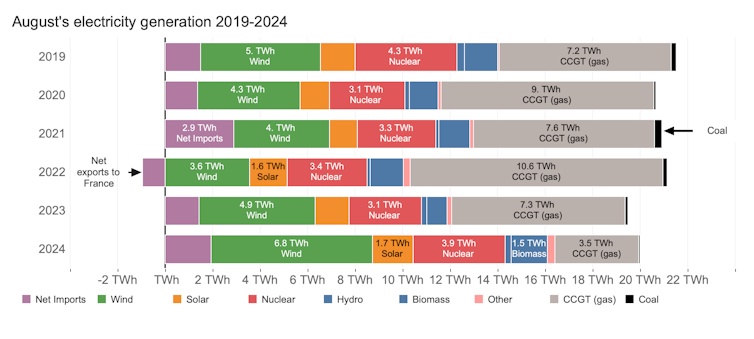

Elexon/National Grid ESO/Grant Wilson

Compared with 2023, electricity generation from combined cycle gas turbines in August 2024 more than halved thanks to renewables and imports.

The standout increase in renewable energy for August was wind, which generated 6.8 TWh, or 33% of August’s electrical demand, compared with 25% in August 2023. Apparently there was one upside to the wet and windy weather that swept Britain this summer. This trend will continue, with significant wind capacity additions planned by 2030.

Britain’s energy system is changing

As renewable energy sources become more prevalent, weather patterns will play an increasingly important role in power generation. This will affect both the supply of electricity and its demand. The inherent risks are something that energy system planners must address to provide stability and security of supply by supporting a range of low-carbon fuels.

So far during 2024, CO₂ emissions from electricity are nearly 6 million tonnes lower than they were at the same point in 2023. Britain is on track to end the year with power sector emissions of between 30 and 35 million tonnes, which would be 40-50% below emissions just five years ago (57 million tonnes in 2019).

Emissions are expected to decrease even as overall electricity demand is likely to rebound from low levels in 2023. Slightly lower electricity prices, and the growing shares of electric vehicles and heat pumps, are contributing to rising demand. These are helping the benefits of clean electricity spread into other sectors, by shifting energy demand from high-carbon liquid fuels (transport) and natural gas (heating) over to electricity.

It may well be that 2023 marks a low point for annual electricity demand for Britain. Future growth in low-carbon heat and transport, plus data centres, AI and robotics, will push demand upwards. However, it is also inevitable that the record lows for emissions and fossil fuel generation in 2024 are merely a step towards even lower levels, as natural gas generation loses market share to renewable generation over the coming years.

This year’s milestones are encouraging signals that Britain’s energy transition is gathering much needed pace, paving the way for a future with less reliance on volatile imported fossil fuels and less impact on the environment. Indeed, by the end of September 2024, the UK’s last coal-fired power station will close, leaving gas as the only fossil fuel left to phase out.

Grant Wilson, Associate Professor, Energy Systems and Data Group, Birmingham Energy Institute, University of Birmingham; Daniel L. Donaldson, Assistant Professor of Electrical Engineering, University of Birmingham, and Iain Staffell, Senior Lecturer in Sustainable Energy, Imperial College London

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved