By Leonie Fleischmann, City St George’s, University of London | –

(The Conversation) – Western political leaders were quick to argue that the killing of Hamas leader, Yahya Sinwar, on October 17 presented a window of opportunity. Perhaps the decapitation of the militant group’s senior command would be a chance for renewed ceasefire talks and the release of the Israeli hostages.

The US president, Joe Biden, urged the Israeli government the following day to “make this moment an opportunity” to end the war in Gaza. But Israel had already launched a major operation in northern Gaza. On October 12, the IDF posted a message in Arabic on social media sites warning civilians living in an area designated as D5 on Israel’s grid map of Gaza to evacuate. It said the area would soon be a “dangerous combat zone” and ordered people to move to safe areas in the south of Gaza.

This process has continued as the IDF has renewed its offensive in the north of the enclave, with an estimated 400,000 people affected, about 20% of the population of Gaza. The UN reported on October 21 that only a “trickle” of food aid has been allowed into north Gaza over the previous week. The Israeli military has denied this. But it has also been reported that the emergency polio vaccination campaign in north Gaza has had to be suspended, due to Israeli bombardment and a lack of access to UN personnel.

The forcible transfer of a population during war is illegal under international law, as is denying access to humanitarian aid for civilians. But there are fears that there is a plan to move Palestinians out of north Gaza in a plan which could pave the way for settlers to move in.

The liberal Haaretz newspaper, a consistent critic of the Netanyahu government, published an editorial on October 22 saying that there was mounting evidence that Israel is now pursuing a policy of siege and starvation to force the complete evacuation of the civilian population of northern Gaza. In doing this, the newspaper said, Israel is implementing the now notorious “generals’ plan”. It asserted:

Make no mistake, [the generals’ plan] is a war crime, and it runs contrary to UN Security Council decision 2334, which states that land may not be taken through force, referring to acts of war.

Military plan or land grab?

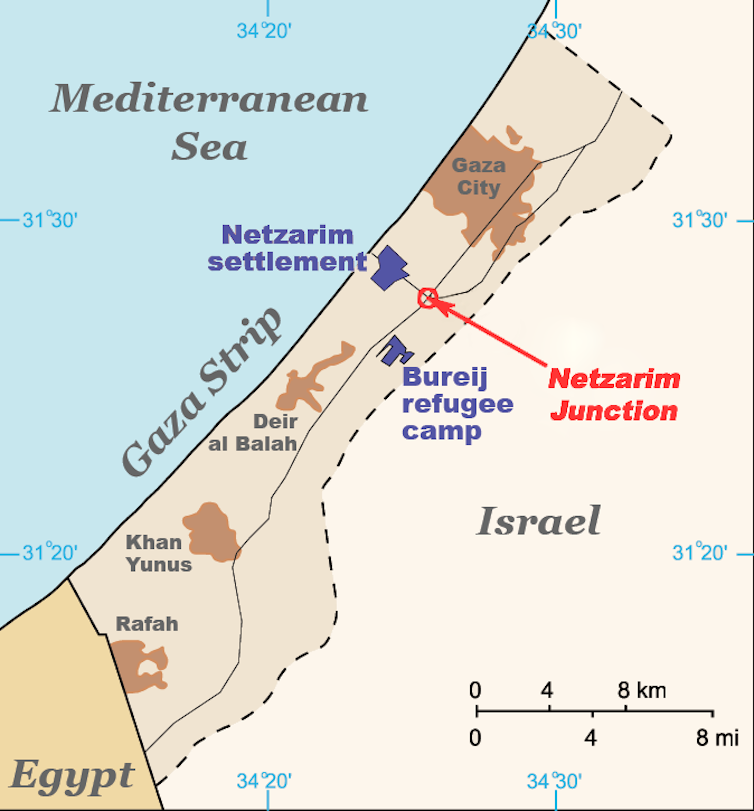

The “generals’ plan” is attributed to retired Maj. Gen. Giora Eiland, a former head of national security in Israel. As a strategy to defeat Hamas (something which has proved elusive in 12 months of bitter fighting in Gaza) it proposes the wholesale transfer of north Gaza’s population south beyond the Netzarim corridor. A siege would be imposed on those who remain.

ChrisO/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

In late September Eiland argued in an interview with Haaretz that “it’s permissible and even recommended to starve an enemy to death, provided you’ve allowed the civilians corridors of exits beforehand. And that is exactly what I am proposing”.

Israeli prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, recently told US secretary of state, Antony Blinken, that Israel is not planning to lay siege to northern Gaza. But the evidence of the military’s actions on the ground suggests otherwise. Since October 6 the IDF has been conducting what it calls a “clearing operation” in Jabalia, north of Gaza City, channelling civilians south while launching airstrikes against the Jabalia refugee camp, where it says units of Hamas are embedded.

Changing the reality

There is widespread concern that the end game in north Gaza will include the return of settlers. A conference on October 22 attended by members of the ruling Likud Party, including several ministers in the Netanyahu government, heard the national security minister, Itamar Ben Gvir, assert that “encouraging emigration” of Palestinian residents of Gaza would be the “most ethical” solution to the conflict. The finance minister, Bezalel Smotrich, told journalists on his way to the conference that the Gaza Strip was “part of the Land of Israel” and that “without settlements, there is no security”.

Settlers were moved out of the the Gaza Strip in 2005, under the then prime minister Ariel Sharon’s Disengagement Plan. The plan dismantled 21 settlements in the Strip, relocating an estimated 8,000 settlers. Many vowed at the time that they would return one day.

CIA/Wikimedia Commons

There was a Jewish presence on the Gaza Strip from biblical times until 1929, when they were driven out during the Arab revolts, in which 133 Gazan Jews were killed. After the six-day war in 1967, Israel occupied the Sinai Peninsula, the Gaza Strip, the West Bank, East Jerusalem, and the Golan Heights. In the aftermath of the war, the main focus of settlement was national security, rather than religious ideology. Here the driving force was Israel’s deputy prime minister, Yigal Allon, who believed that national security could be guaranteed by building settlements.

As a consequence, in the 1970s, the Labour government established the initial modern settlements in the Gaza Strip. The settlements divided the enclave such that the Palestinian inhabitants in each area were isolated from each other, thus enabling Israeli control.

UK-based historian Ahron Bregman, a former Israeli army officer (who has written for The Conversation on the conflict between Israelis and Palestinians), warned in a post on X about how national security could once again be used as a pretext for settlements to be established in north Gaza.

“Resort,” Digital, Dream / Dreamland v3

The current operation in northern Gaza feels like a particularly ominous moment, not only in the Hamas-Israel war, but in the history of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Rather than use the opportunity of a weakened Hamas to reach a ceasefire and hostage deal and allow the people of Gaza to attempt to rebuild their shattered lives, Israel appears to be illegally, immorally and irreversibly changing the realities on the ground.

Leonie Fleischmann, Senior Lecturer in International Politics, City St George’s, University of London

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved