By Diego Alburez-Gutierrez, Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research and Enrique Acosta, Autonomous University of Barcelona | –

The hardship of war does not end when the shooting stops, as every wartime death leaves behind family members whose struggle will go on for decades, if not generations. Millions of these bereaved survivors have lost their kin, including parents, children, siblings, cousins, spouses and friends, with scores being added daily by wars like those currently ravaging Gaza, Lebanon, Ukraine and Sudan.

As well as plunging lives into mourning and sorrow, wars destabilise the basic foundations of wellbeing, health, and family care. They can also fuel desires for retribution and, coupled with intimate familiarity with violence and feelings of injustice, propel cycles of war far into the future. If we are to break these deadly patterns, we need to pay close attention to bereavement among the survivors of war.

Measuring war bereavement

In our recent study, we quantified the extent to which family bereavement outnumbers war casualties, as each wartime death entails the loss of a relative for various members of the surviving population. This is exacerbated in the context of protracted wars in which people can accumulate bereavements – someone might lose a parent to war when they are young, and then a child to the same war in old age.

In Palestine, one of the regions most affected by war in the last decade, there were an estimated 10,500 conflict fatalities between 29 September 2000 and 6 October 2023, and more than 41,000 fatalities since October 7, 2023. On average, each of these deaths has resulted in 1.7 grieving parents and 1.9 grieving children. This means that around 1 in every 43 surviving Palestinians has lost a child to the conflict, and 1 in every 59 Palestinians has lost a parent to war during their life.

These are, of course, population-level averages: some individuals have experienced a great deal more family deaths than others. The real numbers may also be much higher – a Lancet study accounting for indirect deaths estimates over 186,000 lives have been lost in Gaza since 7 October 2023.

Psychological and social damage

War bereavement leaves long-lasting scars in populations because bereaved survivors carry the experience of loss throughout their lives. Wars end, but the trauma endures.

Consider the case of the ongoing war in Gaza. According to our calculations, bereavement levels in the territory will remain extremely high in the decades to come, regardless of the war’s future development. Even if all hostilities were to cease immediately, we estimate it would take 50 years of uninterrupted peace to reduce the proportion of bereaved individuals in the Palestinian population to a quarter of current levels.

This population of bereaved survivors of war deserves special attention. Studies have shown that they are at a higher risk of prolonged grief disorder, depression, suicidal ideation, substance use disorders, and physical diseases.

The sudden death of kin is not only an emotional shock, it can also result in the loss of resources and support for those left behind. For instance, the death of a parent deprives young children of important financial and emotional resources at a key stage of their emotional and physical development. This can be highly detrimental for the child, or even fatal when coupled with the destruction of infrastructure like schools and health clinics.

Similarly, wellbeing in old age can be irreversibly damaged by the loss of children who act as caregivers. In fact, older adults are becoming increasingly at risk in wars around the world.

The political impact of family bereavement

The collective experience of losing kin affects shared perceptions of a conflict. While bereavement is a fact of life, war deaths are massive, untimely, unexpected and violent, creating the ideal conditions for collective trauma to take root and endure over time.

This is compounded by the fact that war casualties tend to be clustered within family groups and, as a result, some families experience the loss of multiple members to war. The targeted bombing of residential buildings in Gaza, for example, has brought about bereavement hotspots in which individuals experience much higher levels of bereavement compared to other members of the population.

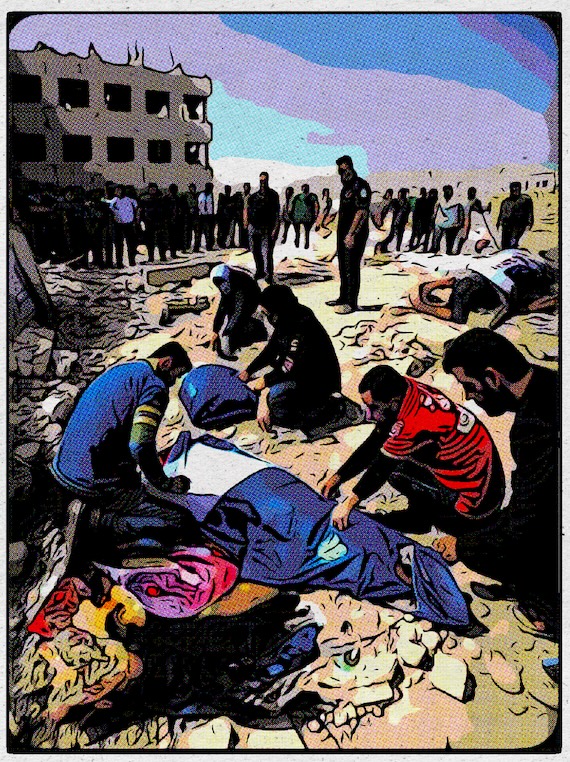

“Mourning,” Digital, Dream / Dreamland v3, Clip2Comic, 2024.

The higher the levels of bereavement in a population, the more likely it is that individuals will have a deeper personal and emotional connection to the armed conflict. If a war is protracted, these experiences of loss will accumulate, eventually leading to a situation where members of different generations share similar experiences of violent kin loss. This makes finding a political solution to armed conflict very difficult in the long run.

Moving towards reconciliation

Large scale, violent kin loss has the potential to reshape the very fabric of society. It pushes young people towards radical ideologies, dictates political decisions, influences religious traditions, and drives further escalation of violence.

However, it may also foster a desire for reconciliation and reparation, pushing individuals toward seeking peace and justice. Reconciliation processes are complex, often involving diplomatic engagement, economic support agreements, the establishment of truth and reconciliation committees, and careful mediation. Engaging with those who lost family members and addressing their demands for accountability and justice are critical components of this process.

It is imperative that we protect lives, and not just on humanitarian grounds – reducing war deaths will curtail the growth of bereaved populations, and break the cycles of violence fuelled by pain, resentment, and trauma. Ultimately, this is essential for ensuring stability and security on a global scale.

Diego Alburez-Gutierrez, Group Leader, Kinship Inequalities Research Group, Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research and Enrique Acosta, Demógrafo, investigador en el Centre d’Estudis Demogràfics (CED), Autonomous University of Barcelona

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved