By Dennis Altman, La Trobe University | –

In May 2023, renowned Black American writer Ta-Nehisi Coates spent ten days in the West Bank and Israel, where he spent half his time with Breaking the Silence, a group of former Israeli soldiers who now oppose the occupation.

Going to Palestine was “a huge shock to me”, he told the New York Times. Coming back, he felt, as he told US journalist Peter Beinart, “a responsibility to yell” about what he’d seen – which he describes as apartheid and compares to the segregated Jim Crow South in the United States.

As he was writing his new book, The Message, the October 7 Hamas attacks happened, followed by the ongoing war in Gaza. He doesn’t cover these events in the book, though he has talked about them in interviews, including one in which he described the decision not to allow a Palestinian state legislator to speak at the Democratic National Convention that nominated Kamala Harris as “deeply inhumane”.

Review:

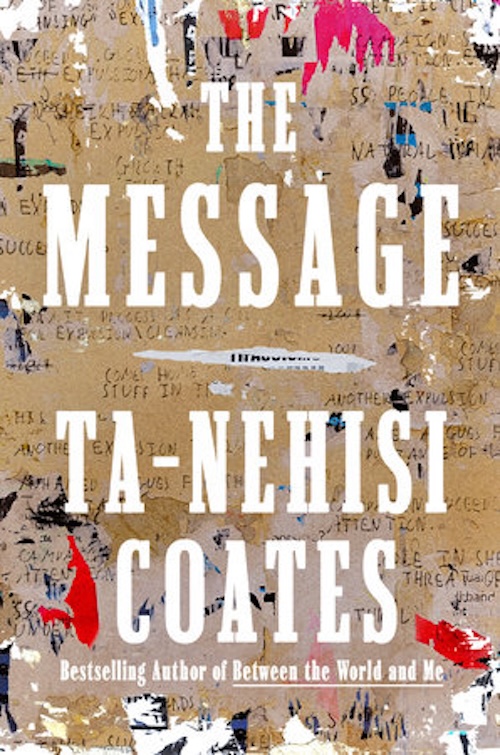

The Message – Ta-Nehisi Coates. Penguin Random House. Click here to Buy.

Coates is among the most celebrated and accomplished writers in the US. He is also, importantly, a Black writer in a world still dominated by white Americans. He first grabbed attention with a 2014 essay on America and slavery in The Atlantic, titled “The Case for Reparation”. Subsequently, he has written five books, including a novel, The Water Dancer, set on a Virginia slave plantation. He was even hired to write a Superman movie.

Coates has deliberately cast himself as part of the legacy of Black American writing, most notably through lyrical language that echoes the writer and civil rights activist James Baldwin. After reading his memoir about the experience of being Black in America, Between The World and Me, fellow writer Toni Morrison said she regarded him as Baldwin’s heir.

Slavery, censorship and culture wars

The Message is a series of three essays directed at Coates’ writing students at Howard University. In it, he chronicles three very different journeys. The final essay, about his trip to Israel–Palestine, takes up almost half the book.

His first trip is to Senegal, in search of the origins of Afro-American slavery. In the second, he visits a small town in South Carolina where there have been attempts to ban Between The World and Me from being taught in schools. Not surprisingly, all three sections are haunted by his awareness of racism and colonialism. His name, Ta-Nehisi, is a deliberate reference to the ancient Egyptian term for the kingdom of Nubia, sometimes translated as “land of the Blacks”.

Coates recognises that Western defence of slavery depended on defining the African as subhuman, just as Western colonialism justified itself with an ideology of racism. In Senegal, he visits the island of Goree, for four centuries the largest slave trading port on the African coast, now a world heritage site.

But like other African-American writers who have gone to Africa in search of their roots, he recognises that he is an outsider: “We have a right to our imagined traditions, to our imagined places, and those traditions and places are most powerful when we confess that they are imagined.”

These thoughts echo again when Coates struggles to come to terms with Israel, where both Palestinians and Israelis hold deeply felt emotional connections to the land, which makes compromise difficult.

In Chapin, South Carolina, teacher Mary Wood faced calls for her firing for teaching Between the World and Me, and pushed back against an attempt to ban her teaching it. The Message is frustrating in its lack of detail about the case, but Woods’ battle with the local school board has been widely reported as part of ongoing conflict within the US over censorship of books dealing with racial and sexual injustice. Coates is too focused on the fate of his own book to stand back and analyse the bigger conflict it represents.

America’s culture wars, which are echoed in Australia, are essentially battles over how to define a national identity – or, as Coates writes, to “privilege the apprehension of national dogmas over the questioning of them”. Our attack on “black armband” history (as named by Geoffrey Blainey in 1993) is paralleled by right-wing American denials of the centrality of slavery to the creation of the US, and debates over “critical race theory”.

Coates: Israel is not a democracy

Coates’ account of his trip to Palestine has been the most controversial aspect of his book. Significantly, he begins this section with an account of his visit to the World Holocaust Remembrance Center.

His sense of the horrors recorded there makes his account of Israeli occupation and dispossession of Palestinians more poignant. Reflecting on the memorial, Coates writes: “Every time I visit a space of memory dedicated to this particular catastrophe I always come away thinking that it was worse than I thought, worse than I could ever imagine.”

Aware of the racism that surrounds him as a Black American, Coates can imagine himself as both Palestinian and Israeli. This generosity of imagination does not prevent critical analysis. His accounts of life in the occupied West Bank underline the reality that Israel has imposed a regime that is effectively based on the subordination and dispossession of Palestinians – and a deliberate attempt, he writes, to deny any possibility of a genuine two-state solution.

The Israeli lobby is outraged by claims Israel has created an apartheid regime: many see the term as motivated by anti-Semitism. This is the implicit message of much of the pro-Israeli lobby, as summed up in the demands that Australian universities adopt a particular definition of anti-Semitism.

The strength of Coates’ analysis is that he minimises neither the reality of anti-Semitism, nor that of Israel’s domination of Palestinians. Defenders of Israel struggle to accept that once-persecuted people can become the persecutors. Yet, as Coates writes, “There was no ultimate victim, that victims and victimizers were ever flowing”.

In Coates’ view, Israel is not a democracy. To claim otherwise, he believes, is to deny the reality of Israel’s effective control of seven million Palestinians living on the West Bank and Gaza, who are now subject to dispossession and destruction in ways that resemble the worst carnage of World War II.

It is extraordinary that our politicians who can extol the virtues of multiculturalism remain blind to the realities of Israeli occupation, and indeed to the growing assertion of Jewish supremacy over those Israeli residents, around 25% of whom are not Jewish.

“Those who claimed Israel as the only democracy in the Middle East were just as likely to claim that America was the oldest democracy in the world,” he writes. “And both claims relied on excluding whole swaths of the population.”

Coates comes closest to explaining this paradox in his account of a plaque in Jerusalem that bears the name of a former US ambassador and proclaims “the unbreakable bond” between the two nations. This bond, it reads, is based on the shared ideals of the Bible, language that reverberates among many evangelical Christians today.

For millions of Americans, criticism of Israel becomes criticism of the US itself. The strength of the Israeli lobby in the US is enormous. The Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC), which spent over 100 million dollars this year, helped at least 318 American politicians win their seats in the recent US elections.

Not surprisingly, Palestinian voices go largely unheard in the US. Coates points to a study that demonstrates over a 50-year period ending in 2019, only 2% of opinion pieces discussing Palestine had Palestinian authors. (The study covered four major mainstream publications, including the New York Times and Washington Post.)

Honesty and egocentrism

Many reviews of The Message have been critical. Paul Sehgal in The New Yorker described it as “a public offering seemingly designed for private ends, an artefact of deep shame and surprising vanity which reads as if it had been conjured to settle its author’s soul”. I think the book is stronger than Sehgal suggests.

The Message is written as a conversation with Coates’ writing students, and his growing realisation that “becoming a good writer would not be enough”. He acknowledges his own limits: “I had gone to Palestine, like I’d gone to Senegal, in pursuit of my own questions and thus had not fully seen the people on their own terms.”

In fact, though, he did pay attention. The section on Palestine includes conversations with both Palestinians and Israelis, as well as references to the voluminous literature on the conflict. (Unfortunately, he does not include footnotes or a bibliography.) Since the publication of this book, Coates has become an active advocate for Palestinian rights. He recognises he has come late to this debate.

Yes, as his own words suggest, there is egocentrism in The Message. But I read it as an honest attempt to think through how a writer can best influence the world when confronted by slaughter and inhumanity. The Message is an unashamedly personal book. At times, it reads as if the author were in analysis, working through the privileges and burdens of being a successful writer and intellectual.

At several points, he refers to himself as both a writer and a steward, with an obligation to speak out about injustice to others. He writes of his books as his children, which “leave home, travel, have their own relationships, and leave their own impressions”. (He hints that of his five “children”, his favourite is his novel, The Water Dancer.)

I only wish the ardent defenders of Israel who occupy our parliament could be persuaded to read Coates’ book. At least it might persuade them that criticism of Israel’s refusal to recognise the claims of Palestinians is not equivalent to anti-Semitism.

Dennis Altman, Vice Chancellor’s Fellow and Professorial Fellow, Institute for Human Security and Social Change, La Trobe University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved