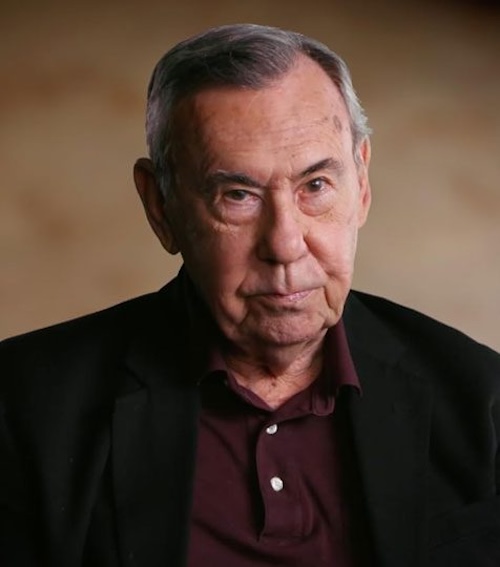

Gary Sick was the national security advisor to President Jimmy Carter. He was present at the White House during some turbulent times- the Iranian revolution, Camp David Accord and more. He had served previously under President Ford and, for a short period, under Reagan.

Later, he taught at Columbia University and for nearly 30 years ran the website Gulf 2000 which has been a thoughtful forum for discussions regarding Middle East politics for its members- analysts and commentators alike.

He is emeritus member of the board of directors of Human Rights Watch and serves as founding chair of the Advisory Committee of Human Rights Watch/Middle East.

He has authored three books among them, October Surprise: America’s Hostages in Iran and the Election of Ronald Reagan.

He is now retired.

Gary Sick. Courtesy Columbia University.

Fariba Amini: There are Iranians as well as Americans who believe in conspiracy theories. They are convinced that the Iranian revolution was a byproduct of the meeting in Guadaloupe or that it was Jimmy Carter’s human rights policy that brought about the revolution in Iran. You said in an interview that while Jimmy Carter was president, the Shah and his aides were not worried about a revolution and that they claimed they had everything under control. You were at the White House while telegrams were coming from Tehran about the deteriorating circumstances. What do you say to these people?

Gary Sick: First of all, the Guadaloupe meeting [4-7 January 1979] was the very end of the revolution, not the beginning. It was after most of the revolution had already taken place, and demonstrations were still going on, Khomeini’s presence in Paris and then in Tehran, etc… The Guadaloupe meeting was an attempt by Western leaders, Carter and a handful of others, to literally decide what happened in the revolution and where it would lead. I’ve never heard that theory that the Guadaloupe meeting was the cause of the revolution, it was the effect of revolution. The quotation you were quoting was not the quotation by me, it was by Richard Helms, who was the head of the CIA and then was the ambassador to Tehran. He went to Iran in the middle of 1978 to seek for himself what was happening and what was going on, and because of his background he had access to everybody he wanted to talk to, including the SAVAK, the military and the Shah himself.

I talked to him sometime after he had come back. He said these were not nervous men, they were not thinking about whether they should flee or what would happen with the revolution. This was in the middle of 1978 and the revolution was underway, but the people around the Shah did not really believe that was going to happen. As far as they were concerned, they stayed very much where they worked, this was their view, and it was wrong. But this was the same view that was true in the United States as well, because the CIA had briefings and white papers that were produced in July and August, which said that Iran was not in a revolutionary, or even a pre-revolutionary, agitation. That was wrong too, very wrong.

The people who were closest to the situation starting with the Shah but going down to his lieutenants and the American intelligence service, all believed that the Shah was in control and that the people who were in the streets were in effect going to be defeated. Why were they so wrong? Well, they were wrong because there was an assumption in their view that the Shah oversaw what was going on and in fact would be able to end it, by taking firm action, cracking down on the demonstrators, putting people in jail, all variety of things he could do, including changes in the government itself. What took them by surprise was that the Shah was not prepared to take a firm action, and in fact actions came hesitantly and they were inconsistent. He would be up one day and relaxed the next day. So, people who were watching what was going on expected him to take a very firm action to end the demonstrations and that didn’t happen.

There was a mess probably not because of how the Shah acted but because of how the military acted. They cracked down and shot people, but there was inconsistency, because he pulled back and did not continue with the crackdown. He imposed martial law in November, but it was incomplete, because in fact the martial law that he imposed he put the chief of staff of the arm forces in charge of the military government, and he was a pussycat, he was not a tough guy. The tough guys, the army generals who could crack down in a variety of ways, they were doing any good, because the Shah was not taking their advice. He was not doing what they suggested, and the Shah had this incredible vision of himself as his almost umbilical relationship with the Iranian public. He said on many occasions that a king does not shoot his own people. Well, he was wrong. That’s not true. Kings shoot their own people all the time and in various circumstances, but the Shah was not prepared to crack down and start shooting people all the time. As a result, all those people who, in summer 1978, believed that the Shah had taken total control were wrong. They were wrong, because they were wrong about the Shah, not because they were wrong about what was going on in the streets.

Fariba Amini: Was the Shah’s decision to leave due to his illness? Or did he not want to leave a legacy of violence vis-à-vis the people? He wanted to leave, knowing that he would never return, in hopes that his legacy would be that of a benevolent monarch.

Gary Sick: He was ill, and I think he didn’t have any expectations. In fact, if you go back and see the timeline, when he was first diagnosed, his doctors’ assessments, and judging from the past, the survival rate was about five years. If you think about it, it was exactly five years from the time he was diagnosed until he died. I don’t know if he fully understood that, or he believed it but he was fading in a significant way. Maybe he thought he knew all well, but he kept it as one of the great state secrets. Absolutely, no one was supposed to know. He had a potentially fatal disease that affected him in an essential way he couldn’t have expected. Perhaps he realized that he had a very serious disease and that it would be fatal. He was aware of every stage that if this fact became public, it would mean that states all around the world would change their views. They would begin to think about what would happen to their relationship with the Shah and who to deal with when the Shah was gone. He did not want that to happen because it was going to weaken his ability to negotiate. So he kept that as a very tight state secret.

I can tell you that the United States government, with all its different activities, did not know with any certainty what was going on with the Shah, and the first time that it knew for sure was when the Shah was in Cuernavaca, and he looked like he was dying. They brought doctors from New York to look at him. He wouldn’t tell them what his problem was, and they thought it was a tropical disease, like malaria or something of that sort. But he wouldn’t tell them, and it was one of his doctors from France came to see him, then he met with Americans who were taking care of the Shah and told them everything about the fact that he had diagnosed with lymphoma and that he was seriously ill, that he had not wanted them to do any kind of operation on him. Keeping that secret while he was on the throne made sense.

After he left Iran keeping that secret was less and less important or useful or necessary, but he kept that anyway. I think he had just come to believe that it was not something he wanted anybody to know, anywhere in the world. And they did not until his doctors finally said what was going on, and then he needed to go to a hospital for emergency treatment, after which he came to New York and Jimmy Carter made that decision to bring him to New York. He could have gone to several other places. Probably he should have. Carter was very reluctant to do that. He had all his advisors gathered at a meeting in one room in the Whitehouse. He went around the room, and they all said they thought they should bring the Shah to the United States for treatment.

Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlevi. Public Domain. Via Get Archive.

Fariba Amini: Why was President Carter reluctant?

Gary Sick: He realized that if the Shah went to the United States the Iranians would react very badly to that. You remember 1953 when the coup took place. The Shah fled to Rome, stayed there for a while and then came back, and reestablish himself on the throne, after the coup taking place. So, Iranians remembered that the Shah had left Iran and used that a basis to come back and reclaim his position on the throne. Carter was absolutely correct. He knew that Iran, both elite and popular, would believe that the Shah going to the United States after a long time in Egypt, Morocco, and the Bahamas, then ending up in Mexico, and that Carter inviting him to the United States, was the first step to regaining the throne. He was right. That was exactly what the students who took the hostages all believed. When Carter was meeting with his advisors, they said, for political reasons, that the Shah was a friend of ours and keeping him out would reject that part of our background. Carter was in the middle of an election campaign and his advisors said from a political point of view let bring the Shah to the United States for treatment and Carter ended up that meeting by saying: “Ok. I hear what you say. Let the Shah come in, but what are you going to tell me when they take our people hostage in Tehran? He predicted that.

Fariba Amini: It seems that Iranians always like to blame “others” when it comes to anything that’s gone wrong in our history. How do you see this?

Gary Sick: Basically, a lot of people were hurt badly by the Shah’s departure and the revolution. They lost money, property, their lands, their culture and history. You have a lot of very important people living in Los Angeles. Are they going to be happy about this? Of course not. When I speak to some of these groups, I say: “Did you stay there and fight for the Shah?” No. They all ran.

You can blame Jimmy Carter if you like, but the people who are really to blame are the people who were around the Shah. They are looking for an excuse. For somebody who wants to believe that Jimmy Carter invited the Ayatollahs to take over, if they really believe that you’ll never persuade them, because it’s a very convenient argument, which means that they are not to blame, but somebody else is. I don’t blame them necessarily, except to say that it’s not true. There’s nothing else to be said. Jimmy Carter did not spend all his nights and days thinking about how to get rid of the Shah; he had a lot of other things to do at that time.

Fariba Amini: Jimmy Carter was involved in the Camp David accord at that time, and so Iran was not on his priority list, right?

Gary Sick: Camp David is absolutely an example, but he was also involved in Panama Canal Treaty, negotiations with the soviets, and a whole range of issues that were earth-shaking and very important. He didn’t know what to do. The Shah did not ask for help at all, and did not say, would you come and do this for me? He never said that. He never asked for a solution. He had plenty of solutions, however. The military had been working out every day. In fact, there were several formal presentations made to the Shah to put an end to the revolution and street riots led by revolutionaries, clerics and others. The military said, we know who these people are; let us arrest them and hold them so that they are not able to direct the revolution and get them out of the way, and the remaining people there would break up. We’ll make sure to break up demonstrations so that they never occur, and don’t have to shoot everybody to do that. But you have to be present. You must have military forces. Let us in fact break up demonstrations that are taking place.

The Shah was unwilling to do that and turned them down. SAVAK had an approach quite like this, but he turned that down. He was unwilling to take hard action. He had a very equipped army. He had money and he was well equipped, but he didn’t use them. The one exception was Zhaleh square, where the troops there opened fire. That was not on the Shah’s order, but they took it upon themselves to begin shooting, and it was a horrendous outburst in Iran. Zhaleh square event was one of the turning points in Iranian revolution. So, they did shoot people during this and reaction in Iran and elsewhere was very strong and very negative. For whatever reason, either because of the Shah’s attachment to the idea of kingship or the fact that he thought it was against his principles, he was reluctant to take that kind of action.

Andrew Cooper, in his good book The Fall of Heaven, for the first time got permission from the queen and basically interviewed all the people who were in the court at the time, gathering their views about what the Shah was saying, including people who had dinner with the Shah in the palace and what they were thinking at the time. One that came out of that is that he understood better than the people around him how serious the situation was. He was, in fact, smarter and better informed than most people believed. However, he misunderstood that you don’t need to tell everybody. But people like Rafsanjani and others, who were running the revolution on the ground, if they had been arrested and taken away from the whole thing, could have had things sorted out. He was given the opportunity and the suggestion, but he didn’t do it.

I think there are huge unanswered questions about what was going on, because the Shah had all the instruments of coercion he could have used and didn’t have to tell anybody to do this, but he refused to do it. Basically, he sat back and let the revolution take its course without taking very strong actions to stop it. I don’t have answer for that, but I do think that it is the real unanswered question about the Iranian revolution.

US Embassy Hostage Crisis in Tehran, November 4, 1979. Public Domain. Courtesy Picryl.

Fariba Amini: We are now in the aftermath of an election in this country. Trump has won and Harris lost but not by a great margin. What do you think went wrong? Why did the d democrats lose the elections?

Gary Sick: I don’t pretend to be an expert on US politics that is not my principal subject, but I follow them just like everybody else. On this subject, the Democrats are in the midst of carrying out a full scale post-mortem of the election, which I think in the end will turn a few key issues. I see two things that I think are important, one is inflation after the COVID pandemic already because of tremendous amount of spending to stop the pandemic. So, prices went up, and people saw that every time they went to the grocery store or whatever they were doing. They were trying to buy a house; they felt that they saw it, although Biden did everything pretty much according to the book. All the councils by his economic advisors and all his actions were very carefully designed to stop the inflation, which they did. The inflation quit going up, but the prices didn’t go back down.

If you want to criticize the Biden administration, you would say, I can’t abide these price increases. There was a tremendous amount of anger and disappointment that Biden should have made prices go back down. Once it goes up, it almost never comes back down. In fact, there won’t necessarily be deflation. So, that was one thing, and I think there are various explanations for how the Federal Reserve and other forces have combined to save the U.S. economy. You can still make these arguments, but people saw prices go up when they went to the grocery store. That was the fact that the Biden people didn’t succeed. Second thing was that people were looking for some kind of inspirational change and inspirational programs. Biden and Kamala Harris had a very difficult time trying to make their points.

The number of votes Trump got in this election were not that different from his performance in 2016. There is a narrow difference between the two, but it led to Trump being re-elected. That has to be seen as a failure as far as Democrats are concerned, because they didn’t really hold on to their base. They still won around 50% of the votes, but it wasn’t enough to win the election. Those two things—first, inflation, which people saw every day and was much on their minds; and second, instead of rejecting the Democrats and voting for Trump, what many of them did was simply not vote at all—really made a huge difference. I am sure there are lots of other explanations, but these are the two things that strike me as the obvious facts, as far as I’m concerned—the two principal things that led to the Democrats losing. We did discover that, essentially, the whole idea of Trump being a threat to democracy turned out to be an argument that fewer people cared about or were worried about, as compared to, for example, prices in the grocery store. One is theoretical, and the other is practical in daily life.

To be continued . . .

© 2026 All Rights Reserved

© 2026 All Rights Reserved