Decades of agreements and water-sharing deals have often exacerbated tensions rather than resolving them

This post by Mohamed Yousry, was first published in Arabic by Raseef 22* on February 15, 2025. This edited version was translated into English and published on Global Voices as part of a content-sharing agreement.

( Global Voices ) – The West Asia and North Africa region is facing a water scarcity crisis. About 60 percent of the region’s population lives in areas of severe water stress. According to recent reports, the International Water Management Institute has warned that climate change in the region will cause more water stress in the coming years.

In an attempt to solve the problem of water scarcity, many Arab countries have, in recent decades, moved towards concluding freshwater sharing agreements with their neighbors. What are these agreements? What are the most important provisions contained in them? And how are these agreements linked to political and economic conditions?

Water agreements between Iraq and Turkey

Many disputes have occurred between Ankara and Baghdad over the division of the waters of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. As is known, the two rivers originate in Turkey and flow for a long distance in both countries before flowing into Syrian territory.

In 1946, Iraq signed a friendship and good neighborliness treaty with Turkey, to which six protocols were attached; the first protocol included a number of rules regulating the use of the waters of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers and their tributaries.

Later, the two countries agreed on a number of similar protocols in the 1970s, 1980, and 2021, respectively, but the water problem remained and was not resolved.

In April 2024, Iraqi prime minister Mohammed Shia al-Sudani announced, during a joint press conference with Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, the signing of an agreement on water resources management between the two countries that will extend for 10 years.

The agreement also included an invitation to Turkish companies to cooperate in the infrastructure of irrigation projects, implement projects to exchange expertise, and use modern irrigation systems and technologies.

NASA ID: iss069e053879 (Aug. 4, 2023) — Northrop Grumman’s Cygnus cargo craft is pictured from the International Space Station as it approaches while orbiting 260 miles above the Euphrates River in Iraq. Date Created:2023-08-04. Public Domain.

Despite the official welcome of the agreement, most of its provisions were rejected by some Iraqi border and international water experts, who saw it as unclear and “very vague,” and that it “was formulated in a way that allows the Turkish side to evade it.”What’s more, the agreement did not specify the percentage or quantity of water that would be released to Iraq.

The Nile’s Entebbe Agreement

The water shares obtained by the Nile Basin countries were organized under several agreements concluded at different times in the twentieth century. The most prominent of these agreements are the 1902, 1929, and 1959 agreements. Under these agreements, Egypt was granted 55.5 billion cubic meters of Nile water, while 18.5 billion cubic meters were allocated to Sudan.

In May 2010, controversy erupted over these agreements between the upstream and downstream countries, after five of the river’s upstream countries — Ethiopia, Uganda, Kenya, Tanzania, and Rwanda — decided to sign the Nile Basin Legal Framework Agreement in the Ugandan city of Entebbe, known in the media as the Entebbe Agreement. The agreement called for equal distribution among the Nile Basin countries, without taking into account the population, demographics, and development conditions of each country. The agreement confirmed that it would enter into force 60 days after it was ratified by six of the member states.

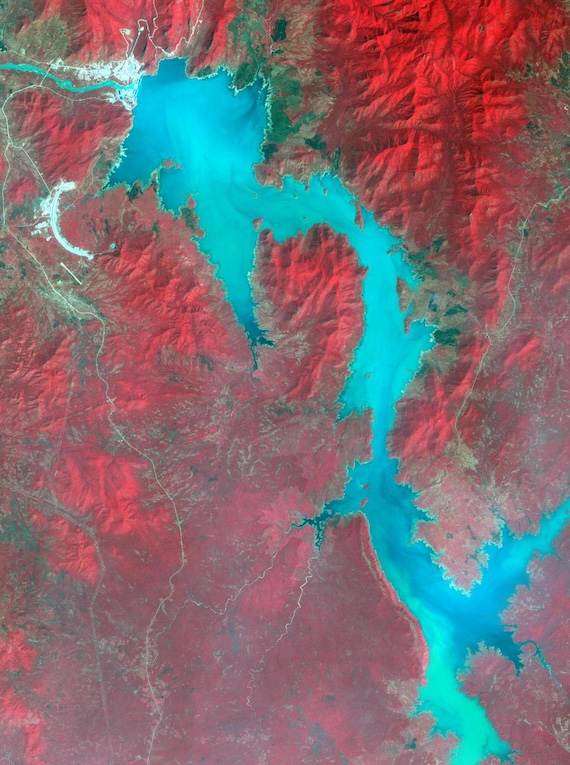

Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam NASA ID: PIA24150. Filling of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) along the Blue Nile River is well under way near the Ethiopia-Sudan border. For a decade, Egypt and Ethiopia have been at a diplomatic stalemate over the Nile’s management. Egypt proposes that Ethiopia should be able to generate hydropower from the GERD while minimizing the harm on downstream communities in Egypt and Sudan. Ethiopia’s objective is to assert control over the Blue Nile, the largest tributary of the Nile River. The image was acquired November 6, 2020, covers an area of 32 by 42.9 kilometers, and is located near 11.1 degrees north, 35.2 degrees east. Date Created:2020-11-10. Public Domain.

Former Egyptian minister of irrigation Mohamed Nasr Allam said in 2010 that Egypt will take all necessary measures to confirm to all international organizations that this agreement is “against international law, not binding on Egypt, and represents an infringement on its water rights.” He also indicated that Egypt will resort to international law to preserve its historical rights in the Nile River.

Recently, the debate over the Entebbe Agreement has returned to the forefront once again, after the Republic of South Sudan announced its ratification of the terms of the agreement.

This cannot be separated from the growing Egyptian–Sudanese concerns in recent years that followed Ethiopia’s construction of the Renaissance Dam on the Nile River. All of these measures come together to create a state of military tension between Egypt and Ethiopia, which has become clear recently.

UAE, Jordan and Israel: Water for electricity agreement

In 1994, a peace treaty was signed between Amman and Tel Aviv, making Jordan the second Arab country, after Egypt, to establish official relations with the State of Israel.

In November 2021, at Expo 2020 Dubai, Israeli energy minister Karin Elharrar and Jordanian water and irrigation minister Mohammad Al-Najjar signed a declaration of intent to cooperate in the production of electricity from solar energy and water desalination between Jordan and Israel.

The declaration stipulated that Jordan, which suffers from a shortage of fresh water while having a great potential for generating electricity from solar energy, would generate electricity from solar energy for Israel, while Tel Aviv, which relies on desalination for most of its water supply, would work to desalinate 200 million cubic meters of water annually for Jordan.

One year later, the two parties advanced in the negotiations, after the three countries, namely the UAE, Jordan and Israel, signed a new agreement on the water and energy project, on the sidelines of the climate conference held in the Egyptian city of Sharm el-Sheikh, in November 2022.

According to the agreement, “the UAE will build a desalination plant in Israel to supply Jordan with water, and at the same time, the UAE will build a huge solar farm in the Jordanian desert, which will provide a percentage of Israel’s electricity consumption.”

In November 2023, Jordan decided to freeze the electricity supply to Tel Aviv, in response to the war launched by Israel on the Gaza Strip. Meanwhile, Jordan asked to extend the agreement for Israel to supply water to Jordan for five years, a request that was met with a reluctant approval for a six months extension due to US pressure.

Water from Iran to Kuwait

Kuwait is another country that relies on desalination of seawater to obtain fresh water. At the beginning of the new millennium, Iran offered to supply Kuwait with the largest amount of its water needs by implementing some huge projects in the Gulf.

In December 2003, the two countries signed an agreement to transfer fresh water from Iran to Kuwait in Tehran, where it was agreed that Iran would transfer 900 thousand cubic meters of potable water daily to Kuwait.

The project consisted of a wide network of pipelines extending from northwestern Iran in the Ahvaz region, specifically from the Karun River at the Karkheh Dam, after which the pipeline would continue to Iranian cities, such as Muhammarah and Abadan, until it crossed the waters of the Arabian Gulf by extending a marine pipeline that avoided passing through Iraqi territory, eventually reaching Kuwait.

The initial agreement stipulated that the project would take 30 years, and its expected budget reached more than USD 1.5 billion. However, as expected, and in conjunction with the issuance of hostile statements exchanged between Iran and the Gulf states, the project sparked widespread controversy in Kuwaiti political circles, and positions and reactions varied between supporters and opponents.

In July 2006, Kuwait officially announced that the negotiations to implement the project had been permanently suspended, due to the political circumstances in the region, especially with regard to the situation in Iraq and the Iranian nuclear file.

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved