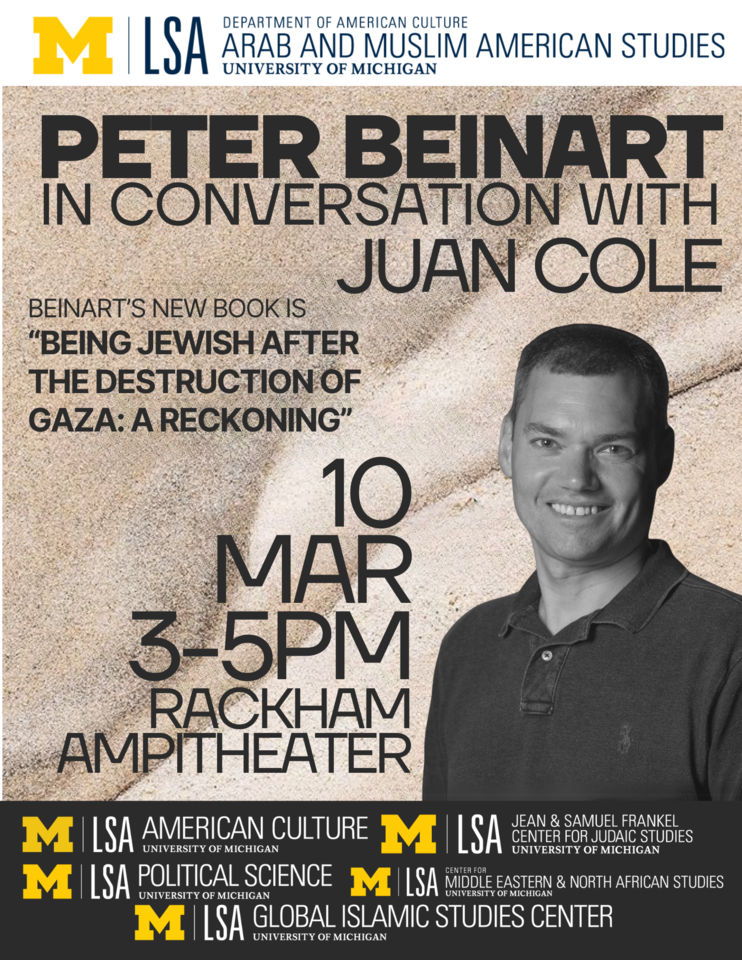

Peter Beinart in conversation with Juan Cole on Beinart’s book, “Being Jewish after the Destruction of Gaza: A Reckoning”; Program in Arab and Muslim American Studies, Department of American Culture, University of Michigan, March 10, 2025.

Excerpt from auto-generated transcript (caveat emptor):

Juan Cole: … I haven’t lost my interest in Middle Eastern spirituality, and one thing I think may escape some readers is the way your book begins -— it refers to some Hasidic stories and stories of the Jewish sages about dialogue with people you don’t agree with, even those you think are heretical. I’d like to provoke you a little here because we’re going to be talking about conflict with a couple of quotes—one from the Quran and one from the Jerusalem Talmud.

The Quran, 5:32, says—this is speaking in the voice of God—”We ordained for the Children of Israel that whoever kills a single soul, except for executing a murderer or a highway robber in the land, it is as though that person had killed the whole world; and whoever saves a soul, it is as though that person saved the whole world.”

This is the Quran talking about what we would call innocent civilians, non-combatants. Obviously, you kill people in war, but it’s addressing murder or the killing of innocent civilians in war, which is forbidden in Islamic law. But the Quran has a footnote—God is citing Jewish lore. This comes from the Mishnah, Sanhedrin 4:5, from the Jerusalem Talmud: “Whoever destroys a single soul is regarded as though he destroyed a complete world, and whoever saves a single soul is regarded as though he saved a complete world.”

The sage who wrote this, and those who believe this is biblical wisdom being distilled rather than something they made up, say that God ordained it so that one man should not say, “My father was greater than thine.” Underlying all of this is the notion that we are all descended from Adam. If someone had killed Adam, none of us would exist—a whole world would have died.

So, that’s the Jewish and Muslim thinking about killing innocent civilians. It’s not very much like the real world, is it?

Peter Beinart: That’s the question?

It’s funny you should bring that text up. As some of you may know, the Jerusalem Talmud is actually considered less normative than the Babylonian Talmud, which was redacted later. Interestingly, the Talmud that was not written in the land of Israel is actually the one considered more authoritative under Jewish law . . .

And it’s particularly strange that you’re citing Tractate Sanhedrin, because I’m actually in the midst of studying it. I do something called “Daf Yomi,” where, if you study a page of Talmud every day, you finish the Talmud in seven and a half years. I’m about five years in, and we’re currently on Tractate Sanhedrin. I can say with some authority—because I just studied it last night—that there are many aspects of Sanhedrin that are far less ethically uplifting than that. Some of it sounds a lot more like the real world.

This just makes the point that religious traditions are vast, speaking in many voices and representing different aspects of human character—some beautiful, emphasizing the infinite dignity of all people, and others sectarian, violent, and extremely troubling.

That’s why I’m reluctant to ever say that people like me “represent Jewish values,” just as I’d be reluctant to say that my politics represent “American values.” Martin Luther King represented American values; Andrew Jackson represented a different set of American values.

So, in a religious tradition -— just as in a national tradition —- one must make a choice about which particular strands to identify with. There is extremely disturbing material in Jewish tradition, just as there is extremely uplifting material.

To me, the question comes back to the point you made at the beginning: the Torah does not start with Jews. The story of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob begins partway into Genesis, but the first humans created according to the Torah are not Jews—they are universal human beings. That is, to me, an undeniable and profound truth about the value of all human life.

What’s happened in much Jewish discourse -— though this is not unique to Jews — is that a kind of ethno-nationalism, a form of tribalism, has swallowed much of the public discourse. That ethno-nationalism does not come from nowhere; one can find citations and sources to support it. But it erases the other voice—the universalistic voice.

This is how we end up in a situation where, in many Jewish institutions, the test of being a “good Jew” is allegiance to the state of Israel. Similarly, for many of Donald Trump’s evangelical supporters, the only thing that seems to matter is whether someone has an American passport—if they don’t, they are seen as worthless. Ethno-nationalism subsumes the complexity of religious tradition and turns the state into God. That, I worry, has happened in much of mainstream Jewish discourse . . .

Peter Beinart, On Being Jewish after the Destruction of Gaza: A Reckoning. Click here to Buy.

Juan Cole: We are discussing Gaza at a time when, I believe, the U.S. government is attempting to make mentioning Gaza a criminal offense. One reason for this is that the crisis in Gaza, and what I think of as surely a genocide, was kicked off by an atrocity. The Hamas party-militia, which has a militant wing—the Qassam Brigades — in alliance with Palestinian Islamic Jihad and some smaller groups, crossed into Israel proper, some using hang gliders. They attacked military bases, killed some 400 Israeli military personnel, and even took over a base.

Then, perhaps not as part of their original plan, they discovered the Nova music festival nearby and attacked it. They took hostages and shot down people. Survivors describe hiding behind garbage bins at Nova, cowering as gunmen hunted them down.

Kibbutzim were invaded — ironically, these were often peace activists who wanted coexistence with Palestinians. A dear friend of mine, Joel Beinin, a prominent historian of the modern Middle East and professor emeritus at Stanford, had a niece, her husband, and their two children kidnapped from a kibbutz. The niece and children were thankfully released in the first pause; the husband was killed. Joel has spent his life advocating for Palestinians. This is a very difficult thing for him —- for all of us.

There are elements on the right, in more than one culture, attempting to frame any criticism of the total war on Gaza and its civilians as support for Hamas. They use this tactic to make opposition to the war taboo.

Peter, in your book, you discuss your heartfelt reactions to October 7th and your response as the war unfolded. Could you tell us more about that?

Peter Beinart: I appreciate the way you started. It seems to me that, going back to the Jerusalem Talmud quote, the fundamental basis for understanding Israel-Palestine -— and more broadly -— is the sanctity of life. People do not surrender that sanctity just because they are part of a state that commits oppression or one built on mass ethnic cleansing. Indeed, this state—the U.S.—was, as well.

That doesn’t mean the lives of people here in this room, living on stolen land, are not precious. It doesn’t mean the distinction between a combatant and a civilian doesn’t matter. That distinction is central to international law and to my moral framework. That’s why, like you, I believe October 7th was an atrocity, a war crime, a series of war crimes.

At the same time, I worry about the dehumanization of Israeli Jews, as if the only thing to know about them is that they are settler-colonists. But even more profoundly, there is a powerful, long-standing dehumanization of Palestinians. This dehumanization enables the destruction of nearly all of Gaza—its hospitals, schools, agriculture, bakeries—and yet most American politicians barely react. They say things like, “They had it coming.”

This kind of rhetoric is only possible because of a deep-rooted dehumanization of Palestinians in American and American Jewish discourse.

One thing I wrestle with is: what does it take to unlock people’s ability to see Palestinians as fully human? Because if you do, you cannot help but be revolted by what is happening.

The forces seeking to dehumanize Palestinians are ascendant in both Israel and the U.S. It’s tied to a broader backlash -— because truly seeing Palestinians challenges American founding myths. Israel’s founding myths and America’s founding myths are strikingly similar. This is why we see such a fierce crackdown on pro-Palestinian activism—it threatens those in power who are brutally hostile to any questioning of America’s founding myths.

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved