Environmental collapse, mismanagement, and ethno-political fault lines are converging in a slow-motion disaster caused by a water crisis

This article by Reza Talebi is written in partnership with UntoldMag.org. The original version was published on April 18, 2025. An edited version is published by Global Voices under a partnership agreement.

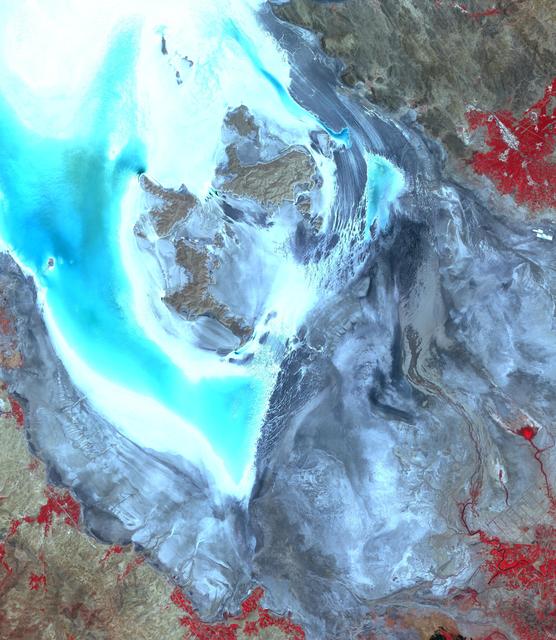

( Global Voices ) – My grandfather was a farmer near Lake Urmia in northwestern Iran. Once the largest lake in Iran, it is now a salt-ridden desert. When the water vanished, his wheat fields dried up. Salt crept over the land, swallowing everything. He died — not suddenly, but slowly. We watched a man who had fathered generations crumble under the weight of thirst. He fled to Hamadan, chasing water, but lost everything — his land, his life, and the water he sought.

While the world fixates on Iran’s nuclear ambitions or internet controls, a quieter and deadlier threat has been unfolding for decades: water scarcity. This crisis is not simply about drought but the result of decades of mismanagement, overextraction, and disregard. Iran is now teetering on the edge of social and ecological collapse.

From the drying wetlands of Gavkhouni to mass migration toward the north, water has become more than an environmental issue — it’s a fault line of ethnic, political, and economic tension transforming Iran’s geography, demographics, and stability.

Iran’s water crisis: A looming catastrophe

Mohammad Bazargan, secretary of the Water and Environment Task Force in Iran’s Expediency Council, recently warned that we are dangerously close to a full-blown water and soil disaster. He said we may soon reach a point where “there won’t be enough room for people to sleep, let alone enough food to eat.”

Internal climate migration is already underway. Villages in arid regions have emptied out. Families forced to abandon homes aren’t seen as refugees, but they are — climate refugees. This slow, creeping exodus has been unfolding for years, largely ignored by decision-makers more focused on social media censorship than survival.

The problem is not just poor management, but a flawed philosophy: domination over nature rather than stewardship. Iran’s water laws, like the Law of Equitable Water Distribution, remain mostly on paper. Successive governments have approached water as something to be controlled and owned, resulting in depleted aquifers, dry rivers, and failing ecosystems.

Agronomist Abbas Keshavarz estimates that Iran has overdrawn its groundwater reserves by 150 to 350 billion cubic meters. Mohammad Hossein Bazargan places irreversible groundwater loss at 50 billion cubic meters over 150 years — water that will never be replenished. Regardless of the figure, both agree: the country is running dry.

Mismanagement and policy failures

Older generations viewed water scarcity as seasonal. If a river ran low, it was blamed on rainfall. But today, even with increased inflows — like the Zayandeh Rud River flowing more now than in the Safavid era — no water reaches the wetlands. The issue isn’t inflow, it’s excessive consumption.

Former Environment Department head Issa Kalantari warned in 2014 that Iran had 15 years of water left for agriculture. That leaves just four years. Iran’s rainfall has remained relatively stable, but underground reserves — fossil waters that take millennia to refill — have been drained at breakneck speed. Ancient “qanat” systems were abandoned for deep wells. Oil wealth ushered in a mindset of extraction and short-term gains.

Lake Urmia, Iran. Public Domain. NASA.

Out of Iran’s original 500 billion cubic meters of fossil water, 200 billion are gone. The remaining 300 billion are saline, unusable for agriculture. Yet agricultural practices remain wasteful: around 70–90 percent of Iran’s usable water goes to farming, with irrigation efficiency at only 30 percent, compared to 50 percent in Turkey or Iraq. Up to 50 billion cubic meters of water is wasted each year.

Urban areas aren’t spared. Cities lose 25–30 percent of their water because of leaks, mismanagement, and outdated infrastructure. By contrast, cities in the global north lose under 10 percent. In many cities, potable water is still used to irrigate green spaces instead of treated wastewater. Meanwhile, industries like Mobarakeh Steel consume 210 million cubic meters of water annually — more than entire provinces.

Iran’s dam-building spree hasn’t helped. In 2012, there were 316 dams; by 2018, that number surged to 647. Many were built without environmental assessments and for political or military purposes. The Latyan Dam near Tehran, once holding 95 million cubic meters, now holds just 9 million. Groundwater levels in Tehran have dropped by 12 meters in two decades, causing land subsidence and destabilizing urban areas.

Military-linked companies, especially those tied to the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), have seized lands near Lake Urmia, cultivating high-water crops like watermelon. Producing one kilogram of watermelon consumes 250 liters of water — yet it remains cheap. Some say Iran offers the “cheapest water in the world,” but at what cost?

Ethno-hydrological and climatic fault lines in Iran

Provinces like Khuzestan and Lorestan are now at the heart of water-related ethnic tensions. In Lorestan, Lur communities accuse the Persian-majority city of Isfahan of “stealing” water through projects like the Koohrang and Beheshtabad canals. These transfers have sparked protests, online backlash, and accusations of “Arab cleansing.”

Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s government tried to appease protestors by allowing unregulated well drilling, worsening the crisis. In Khuzestan, Arab communities accuse the state of favoring Lurs by diverting the Karun River. The Koohrang-3 tunnel submerged entire villages, displacing people and inflaming tensions.

In the northwest, Lake Urmia — shared between Kurdish and Turkish-speaking populations — has dried to a salt crust. The Zab River transfer project, meant to revive the lake, has fueled disputes between Kurdish and Turkish communities. Ethno-demographic shifts are already evident as Azeris migrate to Tehran and Kurds move into Urmia.

Other megaprojects, like transferring water from the Caspian Sea or Oman Sea, are criticized as ecologically destructive and serving industrial elites rather than public need. These projects highlight the government’s reliance on unsustainable, grandiose solutions instead of real reform.

Meanwhile, the government securitizes dissent. Environmental protests are met with repression. Officials rarely speak out while in office. When they do, it’s often too late.

Iran’s water crisis has also spilled across borders — into disputes with Afghanistan, Iraq, Turkey, and Azerbaijan. But the core of the crisis remains internal: a state model unable to listen, adapt, or act.

More than 280 cities face extreme water stress. Rainfall has dropped by over 50 percent in some provinces. Iran ranks fourth globally for water scarcity risk. The country is inching toward “Day Zero,” when taps may run dry completely.

Water is the blood of the earth. It connects people across divides, yet in Iran, it is tearing communities apart. As the rivers vanish, so too do trust, stability, and cohesion. Ethnic tensions, economic despair, and climate migration are converging. The silence surrounding this crisis is deafening.

If ignored, water, not war, may become Iran’s greatest existential threat.

—

Reza Talebi is an academic researcher and lecturer at the University of Leipzig, Department of Oriental Studies and Religious Studies.

The Bridge features personal essays, commentary, and creative non-fiction that illuminate differences in perception between local and international coverage of news events, from the unique perspective of members of the Global Voices community. Views expressed do not necessarily represent the opinion of the community as a whole. All Posts

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved