Ann Arbor (Informed Comment) – Last fall, NASA scientist Colin Raymond and colleagues published an article showing that contrary to expectations, deadly heat and humidity combinations occur along the Persian Gulf at night rather than only during the afternoon. In this part of the Middle East, temperatures are rising at double the average global rate. The climate breakdown is not smooth but affects each region of the earth differently.

A combination of very high temperatures and high humidity can make a place uninhabitable for human beings. Human-caused climate breakdown, through burning coal, oil and fossil gas that release heat-trapping CO2 into the atmosphere, will increasingly put some places off limits for human habitation. Scientists have discovered that it is very difficult to live and work in a place where the temperature is 113º F. and relative humidity is 50%. This combination produces a “wet bulb” temperature (TW) of 95º F.

Note that, confusingly, a 95º F. wet bulb temperature is not the same as the dry bulb temperature of 95º F., which is what you hear on the weather forecast. Wet bulb has its own scale, which combines heat and humidity.

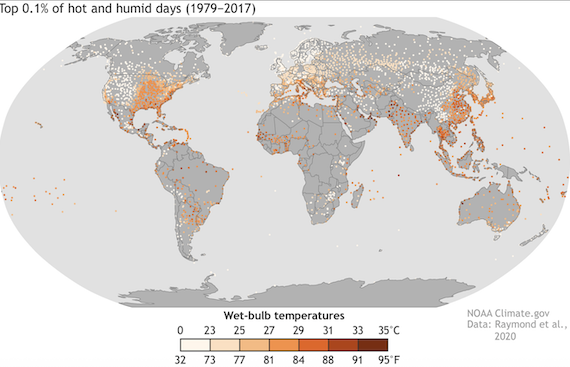

These dangerous heat events are mostly happening in places like South Asia (India, Pakistan, Bangladesh), the coastal Persian Gulf, and the southwest coast of North America. These areas have both very hot oceans nearby and extremely hot land surfaces, which together create the perfect conditions for intense heat and humidity.

Raymond et al. note that there’s solid proof that increasing heat is already causing serious and growing health problems in the region — including more deaths, reduced ability to work, and disruptions to religious and cultural traditions. (The Muslim pilgrimage or Hajj is already affected by the climate breakdown.) Together, Raymond and colleagues warn, these problems could lead to a chain reaction of social issues that are harder and harder to predict. They warn that when compared to the rest of the Middle East and North Africa, the Arabian Peninsula is expected to have the biggest rise in heat-related deaths by the end of this century.

You might think that people could escape some of this heat at night. Unfortunately, this paper finds that it isn’t always true. It says, “the Tw [wet bulb temperature] maximum along the Arabian Sea coast of western India occurs at night.”

NASA: “This map shows locations that experienced extreme heat and humidity levels briefly (hottest 0.1% of daily maximum wet bulb temperatures) from 1979-2017. Darker colors show more severe combinations of heat and humidity. Some areas have already experienced conditions at or near humans’ survivability limit of 35°C (95°F). Map by NOAA Climate.gov, based on data from Radley Horton.” Via NASA .

Temperature readings have documented short spikes in the wet bulb temperature to 35°C (95°F) or more in some cities in Pakistan or the Gulf, which is the level and which people start dropping dead from heat stroke, e.g.:

- “Jacobabad, Pakistan: Recorded occurrences on July 25, 1987; June 5 and 7, 2005; June 27 and 30, 2010; and July 13, 2012.

Ras Al-Khaimah, United Arab Emirates: Experienced such conditions on August 2 and 12, 1995; August 11, 2009; and July 8, 2010.

Jeddah, Saudi Arabia: Noted on August 15, 1999, and June 24, 2010.

Dera Ismail Khan, Pakistan: Reported on August 17, 2017.”

Already 5 years ago, Raymond and his colleagues had published a paper in Science Advances that raised alarms about the rise of uninhabitable hot zones. NASA summarized it here.

Raymond et al. explained that a couple of weather stations had already reported daily wet-bulb temperatures over 35°C (95°F) on multiple days. That’s close to or beyond what the human body can handle for long periods. Thankfully, these extreme conditions usually last only 1 to 2 hours so far.

The scientists said that near coastlines, winds blowing in from the sea during midday and afternoon can suddenly raise humidity levels, especially in dry coastal regions. Remember that deadly wet bulb temperatures are a combination of high heat and high humidity. They point out that along the Persian Gulf, all weather stations with reliable long-term data (from 1979 to 2017) have shown extreme wet-bulb temperatures, reaching above 31°C [87.8º F.] in the top 0.1% of cases (it has happened around 14 times in 39 years).

Satellite and weather model data also confirm that the highest wet-bulb temps are in the Persian Gulf area and nearby land, as well as parts of the Indus River Valley that runs through southern Pakistan.

Hot water is part of the problem, since it produces both heat and humidity. The authors of the 2020 paper said that they noticed in the data that for the first time the average sea surface temperature in the Persian Gulf went over 35°C (95°F) for a whole month in 2017. We’ve already heated up the earth about 1.2º C. [2.16º F.] over the pre-industrial average. They concluded that we don’t even have to breach 1.5º C. (2.7º F.) for the wet bulb temperature to turn deadly over Persian Gulf waters on a regular basis. That means sailors in dhows could be killed by heat stroke as they ply those waters.

Raymond et al. wrote that they also found similar support from another set of ocean data. It showed that sea temperatures in the Persian Gulf have gone over 35°C every year since 1979, and in July to September 2017, about one-third of all readings were above that level. That same summer (2017), about 6% of all wet-bulb temperature readings over the Persian Gulf were at or above 35°C (95º F.0 — an unusually high amount.

The difficulty the study pointed to arises because human beings evolved to deal with excess heat by sweating. In temperate climates, moisture on the skin evaporates, which cools it. As this physics site at Georgia State University notes, “If part of a liquid evaporates, it cools the liquid remaining behind because it must extract the necessary heat of vaporization from that liquid in order to make the phase change to the gaseous state.”

Our normal body temperature is 98.6º F., but if we’re working in the sun in a hot climate with high humidity, our sweat no longer evaporates. We get no cooling effect.

If, as a result, our body temperature rises to 104º F., we suffer from hyperthermia or heat stroke. At that point our brain suffers from dysfunction and we become disoriented, dizzy, nauseated or even delirious or angry. At 106º F. we have a medical emergency on our hands and the possibility of death. At 107º F. we suffer irreversible damage to our brains, as its enzymes fail. The heart, lungs, liver and kidneys can also be damaged. Heat stroke kills us.

If 113º F. plus 50% humidity makes it difficult to live and work in a place, at 122º F. and 80% humidity we would die in only a few hours.

As climate breakdown proceeds because we stupidly keep burning fossil fuels, some places in the Gulf and Pakistan may become uninhabitable. Jacobabad in Sindh, Pakistan is a candidate for such a Wet Bulb Dead Zone. The East India Company officer, Brigadier-General John Jacob CB, (1812–1858), governed that part of Sindh in the 19th century, and the EIC named it for him. The East India Company began mining coal in India in 1774, starting an era of increasingly high carbon emissions; the British also exported coal from Newcastle to the subcontinent. But climate change is having the last laugh on British colonialism, since this very place is emerging as synonymous with

If Jeddah, the major Saudi port city on the Red Sea, becomes uninhabitable, that would be another of History’s little revenge plays, since the Kingdom’s petroleum emissions have been epic, and Saudi officials in the past 40 years have played a major, sinister role in climate denialism and trying to stop the rise of green energy.

But the problem won’t only hit a few Middle Eastern and South Asian cities. Over time, Wet Bulb Dead Zones could grow up in many points of the globe, displacing hundreds of millions of people.

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved