George B. Lambrakis was a State Department Foreign Service officer from 1957 to 1985, after two years with USIS in Vietnam and Laos. He served in Iran during the Islamic Revolution 1978-1979. He is interviewed by Fariba Amini.

Fariba Amini: The first Trump administration abandoned the JCPOA. Why do you think now in his second term, Trump is eager to make a deal? What has changed?

George B. Lambrakis: Trump’s actions can be anybody’s guess. My best guess is that he realized without admitting to anybody that he had made a mistake the first time as it just allowed Iran to develop its nuclear activity and now that Iran is weakened by Israel’s military activity, he has a better chance of browbeating Iran while Israel growls in the background.

Do you believe that Israel has had the intention of bombing Iran, or has it been more of a threat?

I do believe that Israel will try to take out as much of Iran’s nuclear activity if it is backed by the U.S. and, under Netanyahu, is aching to try while it has the most cooperative American president ever. Israel wants to be the only nuclear power in its neighborhood and would also worry if Saudi Arabia or anyone else around it was to develop the bomb.

When did you go to Iran and why?

I went to Iran in the fall of 1976 because my frequent boss, the Assistant Secretary of State for the Near East and South Asia. Assistant Secretary, Ambassador, “Roy” Atherton called to tell me he wanted me in Tehran. I had been considering several more prestigious jobs like political counselor to the admiral in charge of U.S. forces in the Pacific based in Hawaii – being offered by State Personnel to buy me some rest after nearly a year as Deputy Chief of Mission or Charge d’affaires in Beirut during the start of Lebanon’s civil war. I served in between four ambassadors – one of them assassinated just after his arrival – leading to a mass evacuation of American citizens, which our embassy managed without the landing of Marines that Secretary Kissinger and President Ford were considering. It also appealed to me because I had served in Israel and the Arab/Israel desk in Washington, Lebanon, and various other related short assignments dealing with the area but never in the important post of Iran.

My service in Iran can be divided into the first six months of normalcy when I served as acting Deputy Chief of Mission between the departure of former CIA director Ambassador Helms, a Republican, after the election of President Carter and the arrival of Ambassador Sullivan, among the most senior career ambassadors but one new to the Middle East. Then a long period of about two years that saw the developing revolution, and a final period when the Shah and Washington calculated and negotiated what to do about it.

I was surprised to read in [U.S. Ambassador to Iran William H.] Sullivan’s final report on me that I was the first to decide that the Shah was finished, something repeated in a later public meeting by his deputy chief of mission Charlie Naas.

As I see it the signs were obvious at least after the first year, much as this upset all American government assumptions that the Shah would stem the tide of opposition one way or another – as he finally refused to do using force saying he was “a king not a dictator.” After all I was the political counselor and the large CIA staff concentrated almost entirely on the Soviet menace, working with the Shah’s SAVAK [Persian acronym for the Bureau for Intelligence and Security of the State], not covering domestic politics.

You were in Iran during the Revolution. You are one of the few people who predicted that the religious forces would take over when the Shah leaves. How did you come to this conclusion?

Specifically, I shall summarize. Who was the opposition? Not the old Tudeh party that was destroyed, not some of the Mossadegh followers with whom we struck up some contact, but only … the religious people (a complicated issue that we worked on, including other ayatollahs like Shariatmadari – who were finessed by Khomeini). The Shah’s two big decisions that backfired (as I write in my book) was 1. To get Saddam Hussein to kick out Khomeini from Iraq, which improved Khomeini’s influence greatly as he could communicate freely from Paris, and 2, his effort to soil Khomeini’s reputation by insinuating sinful activity in the local paper in Qum, the center of religious activity and training that caused anti-government riots, people killed by the police and then riots repeated in other parts of the country, etc.

Did you or anyone in your entourage know about the Shah’s illness?

We did not know of the Shah’s cancer and neither did the French (and British) embassy even though his doctors were coming from France. Everybody learned in the fall of 1978.

When did you return to the U.S.? I read in the oral history interview that you were at the White House. You mention that there were clear differences between Cyrus Vance and Zbigniew Brzezinski in how to deal with Iran. Can you elaborate? Why didn’t the U.S. not take a more active role?

The main issues then became 1) should the U.S. intervene as it had in 1953 if the Shah did not resort to force as some of his generals were urging or 2) could the only local force, the religious people, be trusted to gain and hold power despite the menace of the Soviet Union and local communists.

I argued that the U.S. should not load itself with a repeat of the 1953 intervention, the memory of which most Iranians condemned, and that the religious people could gain and hold power preventing a Soviet takeover.

Secretary Vance took this position, while National Security Advisor Z. Brzezinski sided with the Shah’s ambassador in Washington who urged that the U.S. cavalry ride to the rescue. A key meeting on this issue took place in the White House situation room where all top U.S. government figures from the Vice President down except Carter and Vance (who was not happy with Brzezinski at the time) attended.

What did Ambassador Sullivan, the last U.S. ambassador to Iran did at that time?

Sullivan sent me to represent him at that meeting and U.S. Airforce General Huyser (with whom I had become quite friendly after his visits to Tehran, and previous contact in Beirut), took me to Washington from Germany and attended the meeting that I describe in some detail in my book. Between that meeting and the additional briefing, I gave to the CIA director the next day, I think Washington decided to accept some confidential letters from Khomeini in Paris that pledged friendship to the U.S. if the U.S. prevented the Shah’s generals from stopping his efforts to return to Iran. The receipt of these letters was never revealed to the embassy, but we figured out the reason General Huyser returned to Tehran and saw the Shah’s generals.

Huyser told me: “George you take care of the civilians, and I will take care of the military.”

What happened after the first Embassy take-over? How did you leave? I am sure you were worried about your safety.

I thought odds were 50-50 when we surrendered during the first embassy takeover though I radiated optimism to those who asked me. Besides, I had many more narrow escapes during the civil war in Beirut just before Iran.

I was always baffled in Tehran never to hear open praise for the Shah at the many parties and various contacts I had with officials until a final such meeting between two very high officials and the U.S. and British ambassadors. in which I was a note taker, in the closing days of the Shah’s reign.

Did you ever meet Ayatollah Khomeini? Did you think that he would become the leader of the Islamic Republic? Did you meet any other leaders of the revolution?

I never met Khomeini. I did see a good deal of [Deputy Prime Minister Ebrahim] Yazdi, including when he led the team that rescued us after the first embassy takeover on Valentine’s Day in February 1979. Before I left Tehran, and after the arrival of some older Iran hands like John Limbert, I was sent to meet Khomeini’s right-hand man, [the cleric Mohammad] Beheshti, but the meeting was inconclusive and Beheshti was murdered by the leftist opposition soon after.

What were some of the best memories you have from your time in Iran?

My best memories of Iran – as of most other countries I served in – was the people that I and my family met including some like the Jaffar boys, family of my chief Iranian assistant in Tehran whom we met again after they fled to California. There were other friends and friendly officials that I don’t need to name. My family also enjoyed developing our skiing skills in the mountains of Tehran.

George Lambrakis was born in Chicago of Greek parents. After his father, a physician, was killed in an auto accident, his mother took him back to Greece at age 2. Six years later, just before Hitler launched the war on Poland, the family returned to the U.S.

George graduated from Princeton University and later attended the School of Advanced International Studies at Johns Hopkins (SAIS).

Interested in politics and foreign affairs, he entered the foreign service and joined the U.S. State Department. He was stationed and served in several countries, among them Vietnam, Israel, Libya and Lebanon.

Ambassador Lambrakis also received an M.A. from the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts courtesy of the State Dept. and a PhD. From George Washington just before retiring from State.

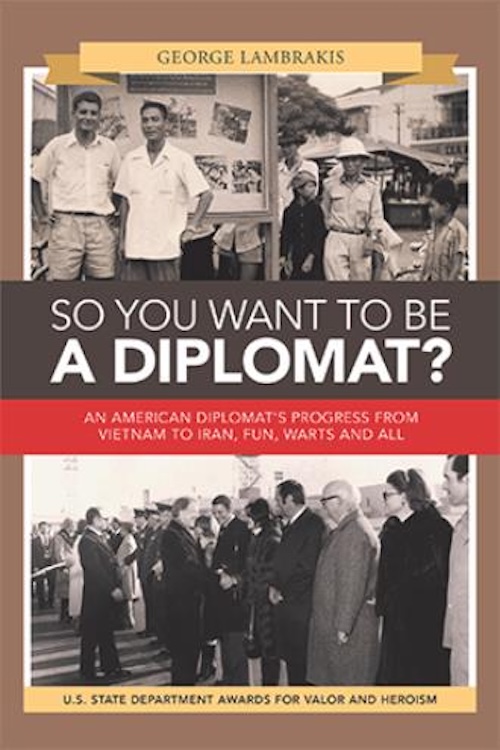

He is the author of “So you want to be a diplomat? An American Diplomat’s Progress from Vietnam to Iran, Fun, Warts and All” which was published in 2019.

As N.Y. Times’ Nicholas Gage wrote: “If any American diplomat practiced his craft under the ancient Chinese curse – ‘May you live in interesting times,’ it was George Lambrakis. Wherever he was assigned, you could bet that all hell would soon break loose.”

George Lambrakis, who received an award for Valor in Heroism from the State Department, will be 94 in June. He is as sharp as ever.

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved