Juan Cole

British social philosopher John Locke was extremely influential on the Founding Generation, and on the US Constitution and Bill of Rights. John Locke had already advocated civil rights for non-Christians, including Muslims, in his Letter on Toleration:

- “Thus if solemn assemblies, observations of festivals, public worship be permitted to any one sort of professors [believers], all these things ought to be permitted to the Presbyterians, Independents, Anabaptists, Arminians, Quakers, and others, with the same liberty. Nay, if we may openly speak the truth, and as becomes one man to another, neither Pagan nor Mahometan, nor Jew, ought to be excluded from the civil rights of the commonwealth because of his religion. The Gospel commands no such thing.”

The last paragraph of Article VI of the Constitution of the United States reads: ‘…no religious Test shall ever be required as a Qualification to any Office or public Trust under the United States.’”

Moreover, the First Amendment of the US Constitution says,

- “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the government for a redress of grievances.”

This amendment forbids Congress from formally supporting one religion or sect over another. The “establishment” of religion in the 18th century meant that the state backed it, collected money from citizens for it, and used police to enforce its beliefs and rituals (Virginia jailed Quakers for refusing baptism).

But the amendment not only forbids the government from supporting a particular religion, it also guarantees that Americans can freely practice any religion they wish. The government cannot “prohibit” the “free exercise” of any religion in the US, including Islam.

The Founding Fathers explicitly mentioned Islam when they spoke of religious freedom:

‘George Washington asked in a March 24, 1784, letter to his aide Tench Tilghman that some craftsmen be hired for him: “If they are good workmen, they may be of Assia, [sic] Africa, or Europe. They may be Mahometans, [Muslims] Jews, or Christian of any Sect – or they may be Atheists …”

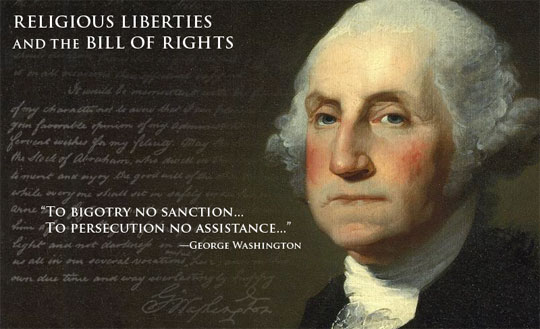

In his letter to the Jewish congregation of Newport, RI, Washington pledged that the “Children of Abraham” would not be made afraid in the United States (implicitly contrasting the new nation’s liberties and personal security with the pogroms of the Old World). It should be noted that Arab Muslims consider themselves, as well, descendants of Abraham through Ishmael:

- ” The reflection on the days of difficulty and danger which are past is rendered the more sweet from a consciousness that they are succeeded by days of uncommon prosperity and security.

If we have wisdom to make the best use of the advantages with which we are now favored, we cannot fail, under the just administration of a good government, to become a great and happy people.

The citizens of the United States of America have a right to applaud themselves for having given to mankind examples of an enlarged and liberal policy—-a policy worthy of imitation. All possess alike liberty of conscience and immunities of citizenship.

It is now no more that toleration is spoken of as if it were the indulgence of one class of people that another enjoyed the exercise of their inherent natural rights, for, happily, the Government of the United States, which gives to bigotry no sanction, to persecution no assistance, requires only that they who live under its protection should demean themselves as good citizens in giving it on all occasions their effectual support.

It would be inconsistent with the frankness of my character not to avow that I am pleased with your favorable opinion of my administration and fervent wishes for my felicity.

May the children of the stock of Abraham who dwell in this land continue to merit and enjoy the good will of the other inhabitants—- while every one shall sit in safety under his own vine and fig tree and there shall be none to make him afraid.”

Washington underlined that in the new social experiment that is the United States, toleration is not merely the indulgence of one group of people by a dominant elite. It is a right, which requires only that the individual be an upright citizen of the new country, which “gives to bigotry no sanction, to persecution no assistance.”

Ben Franklin, the founding father of many important institutions in Philadelphia, a key diplomat and a framer of the US Constitution, wrote in his Autobiography concerning a non-denominational place of public preaching he helped found “so that even if the Mufti of Constantinople were to send a missionary to preach Mohammedanism to us, he would find a pulpit at his service.” Here is the whole quote:

- ‘And it being found inconvenient to assemble in the open air, subject to its inclemencies, the building of a house to meet in was no sooner propos’d, and persons appointed to receive contributions, but sufficient sums were soon receiv’d to procure the ground and erect the building, which was one hundred feet long and seventy broad, about the size of Westminster Hall; and the work was carried on with such spirit as to be finished in a much shorter time than could have been expected. Both house and ground were vested in trustees, expressly for the use of any preacher of any religious persuasion who might desire to say something to the people at Philadelphia; the design in building not being to accommodate any particular sect, but the inhabitants in general; so that even if the Mufti of Constantinople were to send a missionary to preach Mohammedanism to us, he would find a pulpit at his service. ‘

Not only did Ben Franklin not want to ban Muslims from coming to the United States, he wanted to invited them!

Thomas Jefferson wrote in his 1777 Draft of a Bill for Religious Freedom:

- “that our civil rights have no dependance on our religious opinions, any more than our opinions in physics or geometry; that therefore the proscribing any citizen as unworthy the public confidence by laying upon him an incapacity of being called to offices of trust and emolument, unless he profess or renounce this or that religious opinion, is depriving him injuriously of those privileges and advantages to which, in common with his fellow citizens, he has a natural right . . . :

The idea of religious liberty enshrined in the First Amendment was based on an act passed in 1786 by the Virginia state legislature that had been authored by Thomas Jefferson, and which said in part:

“Be it enacted by the General Assembly, that no man shall be compelled to frequent or support any religious worship, place, or ministry whatsoever, nor shall be enforced, restrained, molested, or burthened in his body or goods, nor shall otherwise suffer on account of his religious opinions or belief; but that all men shall be free to profess, and by argument to maintain, their opinion in matters of religion, and that the same shall in no wise diminish, enlarge, or affect their civil capacities.”

One of the arguments raised against this act in the Virginia legislature was precisely that it would allow the free practice of Islam in the Commonwealth. Jefferson’s opponents tried to limit religious freedom to Christianity. Jefferson battled back and won.

James E. Hutson explains:

- “Campaigning for religious freedom in Virginia, Jefferson followed Locke, his idol, in demanding recognition of the religious rights of the “Mahamdan,” the Jew and the “pagan.” Supporting Jefferson was his old ally, Richard Henry Lee, who had made a motion in Congress on June 7, 1776, that the American colonies declare independence. “True freedom,” Lee asserted, “embraces the Mahomitan and the Gentoo (Hindu) as well as the Christian religion.”

In his autobiography, Jefferson recounted with satisfaction that in the struggle to pass his landmark Bill for Establishing Religious Freedom (1786), the Virginia legislature “rejected by a great majority” an effort to limit the bill’s scope “in proof that they meant to comprehend, within the mantle of its protection, the Jew and the Gentile, the Christian and Mahometan.””

Jefferson was ambassador in Paris in 1787 when the Constitution was being drafted, but he corresponded with Madison and strongly urged him to draft a bill of rights that would address religious liberty. Madison was influenced by the 1786 Virginia statute.

That is, the legislative history of the First Amendment demonstrates conclusively that it is rooted in Enlightenment conceptions of religion that saw Christianity, Judaism, Islam and Hinduism as all constituting “religions,” belief in which is a matter of conscience over which civil magistrates should have no control. So I would say that the Constitution implicitly recognizes Islam as a religion, even for an originalist who reads it through eighteenth-century eyes.

Here is Jefferson again: “The most sacred of the duties of a government [is] to do equal and impartial justice to all its citizens.”

– Thomas Jefferson, note in Destutt de Tracy, “Political Economy,” 1816.

Or: “The legitimate powers of government extend to such acts only as are injurious to others. But it does me no injury for my neighbor to say there are twenty gods, or no god. It neither picks my pocket nor breaks my leg.”

– Thomas Jefferson, Notes on the State of Virginia, 1781-82

The US Senate, full of founding fathers, and the Adams government, approved the Treaty with Tripoli (now Libya) of 1797, which included this language:

“As the Government of the United States of America is not in any sense founded on the Christian religion; as it has in itself no character of enmity against the laws, religion, or tranquillity, of Musselmen; and as the said States never have entered into any war or act of hostility against any Mehomitan nation, it is declared by the parties that no pretext arising from religious opinions shall ever produce an interruption of the harmony existing between the two countries.”

The treaty is important for showing the mindset of the fashioners of the American system.

Of course, through the twentieth century the Supreme Court has further refined what it considers to be a religion.

The Newseum Institute explains:

“In the 1960s, the Court expanded its view of religion. In its 1961 decision Torcaso v. Watkins, the Court stated that the establishment clause prevents government from aiding “those religions based on a belief in the existence of God as against those religions founded on different beliefs.” In a footnote, the Court clarified that this principle extended to “religions in this country which do not teach what would generally be considered a belief in the existence of God … Buddhism, Taoism, Ethical Culture, Secular Humanism and others.”

Most recently, the late Antonin Scalia authored an 8 to 1 decision that Abercrombie & Fitch could not discriminate against a Muslim woman wearing a headscarf even if she did not explicitly ask for a religious accommodation. Scalia and his colleagues had no doubt whatsoever that Islam is a religion.

That is, there simply isn’t any question a) that the American legal tradition sees Islam as a religion and that b) its free practice on American soil, without fear of discrimination, is guaranteed by our most precious constitutional instruments, as demonstrated by their legislative history.

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved