Decent apparel at the time of public worship is enjoined in the Qur’an Surah vii 29: “O children of Adam! Wear your goodly apparel when ye repair to any mosque.” Excess in apparel and extravagance in dress are reproved, Surah vii 25: “We (God) have sent down raiment to hide your nakedness, and splendid garments; but the raiment of piety is the best.”

According to the Hidayah (vol iv p 92), a dress of silk is not lawful for men, but women are permitted to wear it. Men are prohibited from wearing gold ornaments, and also ornaments of silver, otherwise than a silver signet ring. The custom of keeping handkerchiefs in the hand, except for necessary use, is also forbidden.

The following are some of the sayings of the Prophet with regard to dress, as recorded in the Traditions. Mishkat, xx c I : “God will not look at him of the Day of Resurrection who shall wear long garments from pride.” “Whoever wears a silken garment in this world shall not wear it in the next.” “God will not have compassion upon him who wears long trousers (i.e. below the ankle) from pride.” “It is lawful for the women of my people to wear silks and gold ornaments, but it is unlawful for the men.” “Wear white clothes, because they are the cleanest, and the most agreeable; and bury your dead in white clothes.”

According to the Traditions, the dress of Muhammad was exceedingly simple. It is said he sued to wear only two garments, the izar, or “under garment” which hung down three or four inches below his knees, and a mantle thrown over his shoulders. These two robes, with the turban, and white cotton drawers completed the Prophet’s wardrobe. His dress was generally of white, but he also wore green, red, and yellow, and sometimes a black woolen dress. It is said by some traditionists that in the taking of Makkah he wore a black turban. The end of his turban used to hang between his shoulders. And he used to wrap it many times round the head. It is said, “the edge of it appeared below like the soiled clothes of an oil dealer.”

He was especially fond of white-striped yamani cloth. He once prayed ina silken dress, but he cast it aside afterwards, saving, “it doth not become the faithful to wear silk.” He once prayed in a spotted mantle, but the spots diverted his attention, and the garment was never again worn.

His sleeves, unlike those of the Eastern choga or khaftan, ended at the wrist, and he never wore long robes reaching to the ankles.

A first, he wore a gold ring with the stone inwards on his right hand, but it distracted his attention when preaching, and he changed it for a silver one. His shoes, which were often old and cobbled, were of the Hazramaut pattern with two thongs. And he was in the habit of praying with his shoes on. [SHOES.]

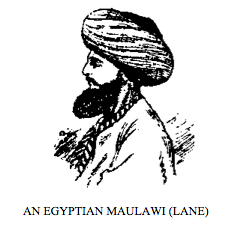

The example of Muhammad has doubtless influenced the customs of his followers in the matter of dress, the fashion of which has remained almost the same in eastern Muslim countries centuries past; for although there are varieties of dress in Eastern as well as in European countries, still there are one or two characteristics of dress which are common to all oriental nations which have embraced Islam, namely, the turban folded round the head, the white cotton drawers, or full trousers, tied round the waist by a running string; the qamis, or “shirt”, the khaftan, or “coat” and the lungi, or “scarf.” The qamis is the same as the ketoneth of the Hebrews, and the of the Greeks, a kind of long shirt with short sleeves the ends of which extend over the trousers or drawers reaching below the knees. The khaftan answers to the Hebrew meil (1 Sam xviii 4), a tunic worn as an outer garment. The Jewish beged, or simlah, must have been similar to the quadrangular piece of cloth still worn as a scarf in Central Asia, and called a lungi, and similar to the ‘aba of the Egyptians. It is worn in various ways, either wrapped round the body, or worn over the shoulders, and sometimes folded as a covering for the head.

The dress of Muslims in Egypt is very minutely described by Mr. Lane in his Modern Egyptians, vol I p 36.

The dress of the men of the middle and higher classes of Egypt consists of the following articles. First a pair of full drawers of linen or cotton tied round the body by a running string or band, the ends of which are embroidered with colored silks, though concealed by the other dress. The drawers descend a little below the knees or to the ankles; but many of the Arabs will not wear long drawers, because prohibited by the Prophet. Next is worn the qamis or “shirt”, with very full sleeves, reaching to the wrist; it is made of linen of a loose open texture, or of cotton stuff, or of muslin, or silk, or of a mixture of silk and cotton in strips, but all white. Over this, in winter, or in cool weather, most persons wear a sudeyree, which is a short vest of cloth, or of a striped colored silk, or cotton, without sleeves. Over the shirt and the sudeyree, or the former alone, is worn a long vest of striped silk or cotton (called kaftan) descending to the ankles, with long sleeves extending a few inches beyond the finger’s ends, but divided from a point a little above the wrist, or about the middle of the fore-arm, so that the band is generally exposed, though it may be concealed by the sleeve when necessary, for it is customary to cover the hands in the presence of a person of high rank. Round this vest is wound the girdle, which is a colored shawl, or a long piece of white-figured muslin.

The ordinary outer robe is a long cloth coat of any color, called by the Turks jubbah, but by the Egyptians gibbeh, the sleeves of which reach not quite to the wrist. Some persons also wear a beneesh, which is a robe of cloth with long sleeves, like those of the kaftan, but more ample. It is properly a robe of ceremony, and should be worn over the other cloth coat, but many persons wear it instead of the gibbeh

Another robe called farageeyeh, nearly resembles the beneesh; it has very long sleeves, but these are not slit, and it is chiefly worn by men of the learned professions. In cold or cool weather, a kind of black woolen cloak, called the abayeh, is commonly worn. Sometimes this is drawn over the head.

In winter, also many persons warp a muslin or other shawl (such as they use for a turban) about the head and shoulders. The head-dress consists first of a small close-fitting cotton cap, which is often changed; nest a tarboosh, which is a red cloth cap, also fitting close to the head with a tassel of dark-blue silk at the crown; lastly, a long piece of white muslin, generally figured, or a kashmere shawl, which is wound round the tarboosh. Thus is formed the turban. The

kashmere shawl is seldom worn except in cool weather. Some persons wear two or three tarbooshes one over another. A shereef (or descendent of the Prophet) wears a green turban, or is privileged to do so, but no other person; and it is not common for any but a shereef to wear a bright green dress. Stockings are not in use, but some few persons in cold weather wear woolen or cotton socks. The above are of thick red morocco, pointed, and turning up at the toes. Some persons also wear inner shoes of soft yellow morocco, and with soles of the same; the outer shoes are taken off on stepping upon a carpet or mat, but not the inner; for this reason the former are often worn turned down at the heel.

The costume of the men of the lower orders is very simple. Theses, if not of the very poorest class, wear a pair of drawers, and a long and full shirt or gown of blue linen or cotton, or of brown woolen stuff, open from the neck nearly to the waist, and having wide sleeves. Over this some wear a white or red woolen girdle; for which servants often substitute a broad red belt of woolen stuff or of leather, generally containing a receptacle for money. Their turban is generally composed of a white, red, or yellow

woolen shawl, or of a piece of coarse cotton or muslin wound round a tarboosh, under which is a white or brown felt cap; but many are so poor, as to have no other cap than the latter, no turban, nor even drawers nor shoes, but only the blue or brown shirt, or merely a few rags, while many, on the other hand, wear a sudeyree under the blue shirt, and some particularly servants in the houses of great men, wear a white shirt, a sudeyree, and a kaftan, or gibbeh, or both, and the blue shirt over all. The full sleeves of this shirt are sometime drawn up by means of a cord, which passes round each shoulder and crosses behind, where it is tied in a knot. This custom is adopted by servants (particularly grooms), who have cords of crimson or dark blue silk for this purpose.

In cold weather, many persons of the lower classes wear an abayeh, like that before described, but coarser and sometimes (instead of being black) having broad stripes, brown and white, or blue and white, but the latter rarely. Another kind of cloak, more full than the abayeh, of black or deep blue woollen stuff, is also very commonly worn, it is called diffeeyeh. The shoes are of red or yellow morocco, or of sheep-skin. Those of the door-keeper and the water carrier of a private house, generally yellow.

The Muslims are distinguished by the colors of their turbans from the Copts and the Jews. Who (as well as other subjects of the Turkish Sultan who are not Muslims) wear black, blue, gray, or light-brown turbans and generally dull-colored dresses.

The distinction of sects, families, dynasties, &c., among the Muslim Arabs by the color of the turbans and other articles of dress, is of very early origin. There are not many different forms of turbans now worn in Egypt; that worn by most of the servants is peculiarly formal, consisting of several spiral twists one above another like the threads of a screw. The kind common among the middle and higher classes of the tradesmen and other citizens of the metropolis and large towns is also very formal, but less so than that just before alluded to.

The Turkish turban worn in Egypt is of a more elegant fashion. The Syrian is distinguished by its width. The Ulama and men of religion and letters in general used to wear, as some do still, one particularly wide and formal called a mukleh. The turban is much respected. In the houses of the more wealthy classes, there is usually a chair on which it is placed at night. This is often sent with the furniture of a bride as it is common for a lady to have one upon which to place her head-dress. It is never used for any other purpose.

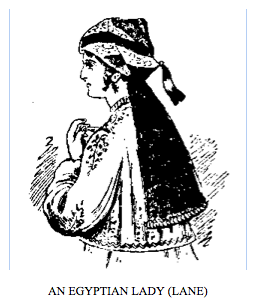

The dress of women of the middle and higher orders is handsome and elegant. Their shirt is very full, like that of the men, but shorter, not reaching to the knees; it is also generally. Of the same kind of material as the men’s shirt, or of colored crape, sometimes black. A pair of very wide trousers (called shintiyan) of a colored striped stuff, of silk and cotton, or of printed or plain white muslin, is ties round the hips under the shirt, with a dikkeh; its lower extremities are drawn up and tied just below the knee with running strings, but it is sufficiently long to hand down to the feet, or almost to the ground, when attached in this manner. Over the shirt and the shintiyan is worn a long vest (called yelek), of the same material as the latter; it nearly resembles the kaftan of the men, but is more tight to the body and arms; the sleeves also are longer, and it is made to button down the front from the bosom to a little below the girdle, instead of lapping over; it is open likewise on each side from the height of the hip downwards.

In general, the yelek is cut in such a manner as to leave half of the bosom uncovered, except by the shirt, but many ladies have it made more ample at that part, and according to the most approved fashion it should be of sufficient length to reach to the ground, or should exceed that length by two or three inches or more. A short vest (called anteree) reaching only a little below the waist, and exactly resembling a yelek of which the lower part has been cut off, is sometimes worn instead of the latter. A square shawl, or an embroidered kerchief, doubled diagonally, is put loosely round the waist as a girdle, the two corners that are folded together hanging down behind; or sometimes the lady’s girdle is folded after the ordinary Turkish fashion, like that of the men, but more loosely.

Over the yelek is worn a gibbeh of cloth or velvet or silk, usually embroidered with gold or with colored silk; it differs in form from the gibbeh of the men, chiefly in being not so wide, particularly in the fore part, and is of the same length as the yelek. Instead of this, a jacket (called saltah), generally of cloth or velvet, and embroidered in the same manner as the gibbeh, is often worn.

The head-dress consists of a takeeyeh and tarboosh, with a square kerchief (called faroodeeyeh) of printed or painted muslin or one of crape, wound tightly round, composing what is called a rabtah. Two or more such kerchiefs were commonly used a short time since, and still are sometime to form the ladies’

turban, but always wound in a high flat shape, very different from that of the turban of the men. A kind of crown, called kurs, and other ornaments, are attached to the ladies’ head-dress. A long piece of white muslin, embroidered at each end with colored silks and gold, or of colored crepe ornamented with gold thread, &c, and spangles rests upon the head, and hangs down behind, nearly or quite to the ground; this is called tarhah, it is the head-veil; the face-veil I shall presently describe. The hair, except over the forehead and temples is divided into numerous braids or plaits, generally from eleven to twenty five in number, but always of an uneven number; these hang down the back. To each braid of hair are usually added three black silk cords with little ornaments of gold &c attached to them. Over the forehead the hair is cut rather short, but two full locks hang down on each side of the face; these are often curled in ringlets and sometimes plaited.

Few of the ladies of Egypt wear stockings or socks, but many of them wear mess (or inner shoes) of yellow or red morocco, sometimes embroidered with gold. Over these, whenever they step off the matted or carpeted part of the floor, they put on haboog (or slippers) of yellow morocco, with high pointed toes, or use high wooden clogs or patterns, generally from four to nine inches in height and usually ornamented with mother of pearl or silver.

The riding or walking attire is called tezyeereh. Whenever a lady leaves the house, she wears, in addition to what has been above

described, first, a large loose gown (called tob or sebleh), the sleeves of which are nearly equal in width to the whole length of the gown; it is of silk, generally of a pink or rose or violet color. Next is put on the burka, or face veil, which is a long strip of white muslin, concealing the whole of the face except the eyes, and reaching nearly to the feet. It is suspended at the top by a narrow hand, which passes up the forehead, and which is sewed, as are, also the two upper corners of the veil, to a band that is tied round the head. The lady then covers herself with a habarah, which for a married lady, is composed of two breaths of glossy, black silk, each all-wide, and three yards long; these are sewed together, at or near the selvages (according to the height of the person) the seam running horizontally, with respect to the manner in which it is worn; a piece of narrow black ribbon is sewed inside the upper part about six inches from the edge, to tie round

the head. But some of them imitate the Turkish ladies of Egypt in holding the front part so as to conceal all but that portion of the veil that is above the hands. The unmarried ladies wear a habarab of white silk or a shawl. Some females of the middle classes, who cannot afford to purchase a habarah, wear instead of it an eezar (izar), which is a piece of white calico, of the same form and size as the former, and is worn in the same manner. On the feet are worn short boots or socks (called khuff), of yellow morocco, and over these women of the lower orders who are not of the poorest class, consists of a pair of trousers or drawers (similar in form to the shintiyan of the ladies, but generally of plain white cotton or linen), a blue linen or cotton shirt (not quite so full as that of the men), reaching to the feet, a burka of a kind of coarse black crepe, and a dark blue tarhah of muslin or linen. Some wear, over the olng shirt, or instead of the latter, a linen tob, of the same form as that of the ladies; and withing the long shirt, some wear a short white shirt; and some, a sudeyree also, or an anteree. The sleeves of the tob are often turned up over the head; either to prevent their being incommodious, or to supply the place of a tarhah. In addition to these articles of dress, many women who are not of the very poor classes wear, as a covering, a kind of plaid, similar in form to the habarah composed of two pieces of cotton woven in small chequers of blue and white, or cross stripes, with a mixture of red at each end. It is called milaych in general it is

worn in the same manner as the habarah, but sometimes like the tarbah. The upper part of the black burka is often ornamented with false pearls, small gold coins, and other little flat ornaments of the same metal (called bark); sometimes with a coral bead, and a gold coin beneath; also with some coins of base silver and more commonly with a pair of chain tassels of brass or silver (called ayoon) attached to the corners. A square black silk kerchief (called asbeh), with a border of red and yellow, is bound round the head, doubled diagonally, and tied with a single knot behind; or, instead of this, the tarboosh and faroodeeyeh are worn, though by very few women of the lower classes.

The best kind of shoes worn by the females of the lower orders are of red morocco, turned up, but generally round, at the toes. The burka and shoes are most common in Cairo, and are also worn by many of the women throughout lower Egypt; but in Upper Egypt, the burka is very seldom seen, and shoes are scarcely less uncommon. To supply the place of the former, when necessary, a portion of the tarhah is drawn before the face, so as to conceal nearly all the countenance except one eye.

Many of the women of the lower orders, even in the metropolis, never conceal their faces.

Throughout the greater part of Egypt, the most common dress of the women merely consists of the blue shirt or tob and tarhah. In the southern parts of Upper Egypt chiefly above Akhmeem, most of the women envelop themselves in a large piece of dark brown woolen stuff (called a hulaleeyeh), wrapping it round the body and attaching the upper parts together over each shoulder, and a piece of the same they use as a tarhah. This dull dress, though picturesque, is almost as distinguishing as the blue tinge which women in these parts of Egypt impart to their lips. Most of the women of the lower orders wear a variety of trumpery ornaments, such as ear-rings, necklaces, bracelets, &c., and sometimes a nose-ring.

The women of Egypt deem it more incumbent upon them to cover the upper and back part of the head than the face, and more requisite to conceal the face than most other parts of the person. I have often seen women but half covered with miserable rags, and several times female in the prime of womanhood, and others in more advanced age, with nothing on the body but a narrow strip of rag bound round the hips.

Mr. Burckhart, in his Notes on the Bedoiuns and Wahays (p. 47), thus describes the dress of the Badawis of the desert:-

In summer the men wear a coarse cotton shirt, over which the wealthy put a kambar, or “long gown,” as it is worn in Turkish towns, of silk or cotton stuff. Most of them, however, do not wear the kambar, but simply wear over their shirt a woolen mantle. There are different sorts of mantles, one very thin, light, and white woolen, manufactured at Baghdad, and called mesoumy. A coarser and heavier kind, striped white and brown (worn over the mesoumy), is called abba. The Baghdad abbas are most esteemed, those called boush. (In the northern parts of Syria, every kind of woolen mantle, whether white, black, or striped white and brown, or white and blue, are called meshlakh.) I have not seen any black abbas among the Aenezes, but frequently among the sheikhs of Ahl el Shemal, sometimes interwoven with gold, and worth as much as ten pounds sterling. The Aenezes do not wear drawers; they walk and ride usually barefooted, even the richest of them, although they generally esteem yellow boots and red shoes. All the Bedouins wear on the head, instead of the red Turkish cap, a turban, or square kerchief, of cotton or cotton and silk mixed; the turban is called keffie; this they fold about the head so that one corner falls backward, and tow other corners hang over the fore part of the shoulders; with these two corners they cover their faces to protect them from the sun’s rays, or hot wind, or rain, or to conceal their features if they wish to be unknown. The keffie is yellow or yellow mixed with green. Over the keffie the Aenezes tie, instead of a turban, a cord round the head; this cord is of camel’s hair, and called akal. Some tie a handkerchief about the head, and it is then called shutfa. A few rich sheikhs wear shawls on their heads of Damascus or Baghdad manufacture, striped red and white; they sometimes also use red caps or takle (called in Syria tarboush), and under those they wear a smaller cap or camel’s hair called maaraka (in Syria arkye, where it is generally made of fine cotton stuff).

The Azenezes are distinguished at first sight from all Syrian Bedouins by the long tresses of their hair. They never shave their black hair, but cherish it from infancy, till they can twist it in tresses, that hang over the cheeks down to the breast; these trousers are called keroun. Some few Aenezes wear girdles of leather, others tie a cord or a piece of rag over the shirt. Men and women wear from infancy a leather girdle around the naked waist, it consists of four or five thongs twisted together into a cord as thick as one’s finger. I heard that the women tie their thongs separated from each other, round the waist. Both men and women adorn the girdles with pieces of ribands or amulets. The Aenezes called it hhakou; the Ahl el Shemal call it bereim. In summer the boys, until the are of seven or eight years, go stark naked; but I never saw any young girl in that state, although it was mentioned that in the interior of the desert the girls, at that early age, were not more encumbered by clothing than their little brothers. In winter, the Bedouins wear over the shirt a piece of pelisse, made of several sheep-skins stitched together; many wear these skins even in summer, because experience has taught them that the more warmly a person is clothed, the less he suffers from the sun. The Arabs endure the inclemency of the rainy season in a wonderful manner. While everything around them suffers from the cold, they sleep barefooted in an open tent, where the fire is not kept up beyond midnight. Yet in the middle of summer an Arab sleeps wrapped in his mantle upon the burning sand, and exposed to the rays of an intensely hot sun. The ladies dress is a wide cotton gown of dark color, blue, brown, or black; on their heads they wear a kerchief called shauber or mekroune, the young females having it of a red color, the old of black. All the Ranalla ladies wear black silk kerchiefs, two yards square, called shale kas; these are made at Damascus. Silver rings are much worn by the Aeneze ladies, both in the ears and noses; the ear-rings they call terkie (pl. teraky), the small nose-rings shedre, the larger some of which are three inches and a half in diameter), khezain. All the women puncture their cheeks, breasts, and arms, and the Ammour women their ankles. Several men also adorn their arms in the same manner. The Bedouin ladies half cover their faces with a dark-colored veil, called nekye, which is so tied as to conceal the chin and mouth. The Egyptian women’s veil (berkoa is used by the Kebly Arabs. Round their waists the Aeneze ladies wear glass bracelets of various colors; the rich also have silver bracelets and some wear silver chains about the neck. Both in summer and winter the men and women go barefooted.

Captain Burton, in his account of Zanzibar, (vol I p 382), says:-

The Arab’s head-dress is a kummeh or kofiyyah (red fez), a Surat calotte (afiyyah), or a white skull-cap, worn under a turban (kilemba) of Oman silk and cotton religiously mixed. Usually it is of fine blue and white cotton check, embroidered and fringed with broad red border, with the ends hanging in unequal lengths over one shoulder. The couture is highly picturesque. The ruling family and grandees, however, have modified its vulgar folds, wearing it peaked in the front, and somewhat resembling a tiara. The essential body clothing, and the succedaneum for trousers is an izor (nguo yaku Chini), or loin-cloth, tucked in at the waist, six to seven feet long by three broad. The colors are brickdust and white, or blue and white, with a silk bordered striped red, black, and yellow. The very poor wear a dirty bit of cotton girdled by a hakab or kundavi, a rope of plaited thongs; the rich prefer a fine embroidered stuff from Oman, supported at the waist by a silver chain. None but the western Arabs admit the innovation of the drawers (suru-wali). The jama or upper garment is a collarless coat, of the best broad-cloth, leek green or some tender colour being preferred. It is secured over the left breast by a silken loop, and the straight wide sleeves are gaily lined. The kizbao, a kind of waistcoat, covering only the bust; some wear it with sleeves, others without. The dishdashes (in Kisawa-hili Khanzu), a narrow sleeved shirt buttoned at the throat, and extending to midshin, is made of calico baftah). American drill and other stuffs called doriyah, tatabuzum, and jamdani. Sailors are known by khuzerangi a course cotton, stained dingy red-yellow, with henna or pomegranate rind, and rank with wars (bastard saffron) and shark’s oil.

Respectable men guard the stomach with a hizam, generally a Cashmere or Bombay shawl; others wear sashes of the dust-colored raw silk, manufactured in Oman. The outer garment for chilly weather is the long tight-sleeved Persian jubbeh, jokhah, or caftan, of European broad-cloth. Most men shave their heads, and the Shafeis trim or entirely remove the moustaches.

The palms are reddened with henna, which is either brought from El Hejaz, or gathered in the plantations. The only ring is a plain cornelian seal and the sole other ornament is a talisman (hirz in Kisawahili Hirizi). The eyes are blackened with kohl, or anitmony of El Sham – here not Syria, but the region about Meccah – and the mouth crimsoned by betel, looks as if a tooth had just been knocked out.

Dr. Eugene Schuyler, in his work on Turkestan (vol I, p 22) says:-

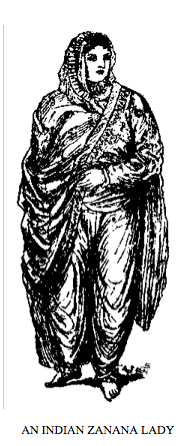

The dress of the central Asiatic is very simple. He wears loose baggy trousers, usually made of coarse white cotton stuff fastened tightly around the waist, with a cord and tassel; this is a necessary article of dress, and is never or rarely taken off, at all events not in the presence of another. Frequently, when men are at work, this is the only garment, and in that case it is gradually turned up under the cord, or rolled up to the legs, so that the person is almost naked. Over this is worn a long shirt, either white or of some light-colored print, reaching almost to the feet, and with a very narrow aperture for the neck, which renders in somewhat difficult to put the head through. The sleeves are long and loose. Beyond this there is nothing more but what is called the chapan, varying in number according to the weather, or the whim of the person. The chapan is a loose gown, cut very sloping in the neck, with strings to tie it together in the front; and inordinately large sleeves, made with an immense gore, and about twice as long as is necessary; exceedingly inconvenient, but useful to conceal the hands, as Asiatic politeness dictates. In summer, these are usually made of Russian prints, or of the native alatcha, a striped or cotton material, or of silk, either striped or with most gorgeous eastern patterns, in bright colors, especially red, yellow, and green. I have sometimes seen men with as many as four or five of these gowns, even in summer they say that it keeps out the heat. In winter, one gown will frequently be made of cloth, and lined with fine lamb skin or fur. The usual girdle is a large handkerchief, or a

Small shawl; at times, a long scarf wound several times tightly around the waist. The Jews in places under native rule are allowed no girdle, but a bit of rope or cord, as a mark of ignominy. From the girdle hand the accessory knives and several small bags and pouches, often prettily embroidered for combs, money &c. On the head there is a skull-cap; these in Tashkent are always embroidered with silk; in Bukhara they are usually worked with silk, or worsted in cross-stitched in gay patterns. The turban, called tchilpetch, or “Forty turns,” is very long; and if the wearer has any pretence to elegance, it should be of fine thin material, which is chiefly imported from England. It requires considerable experience to wind one properly round the head, so that the folds will be well made and the appearance fashionable. One extremity is left to fall over the left shoulder, but is usually, except at prayer time, tucked in over the top. Should this end be on the right shoulder, it is said to be in the Afghan style. The majority of turbans are white, particularly so in Tashkent, though white is especially the colour of the mullahs and religious people, whose learning is judged by the size of their turbans. In general, merchants prefer blue, stripped, or chequered material.

At home the men usually go barefooted, but on going out wear either a sort of slippers with pointed tow and very small high heels, or long soft boots the sole and upper being made of the same material. In the street, one must in addition put on either a slipper of golosh, or wear riding-boots made of bright green horse hide, with turned-up pointed toes and very small high heels.

The dress of the women, in the shape and fashion, differs but little from that of the men, as they wear similar trousers and shirts, though, in addition, they have long gowns, usually of bright-colored silk, which extend from the next to the ground. They wear an innumerable quantity of the necklaces, and little amulets, pendents in their hair, and ear-rings, and occasionally even a nose-ring. This is by no means so ugly as is supposed; a pretty girl with a turquoise ring in one nostril is not at all unsightly. On the contrary, there is something piquant in it. Usually, when outside of the houses, all respectable women wear a heavy black veil, reaching to their waists, made of woven horse hair, and over that is thrown a dark blue, or green, khalut, the sleeves of which tied together at the ends, dangle behind. The theory of this dull dress is, that the women desire to escape observation, and certainly for that purpose they have devise the most ugly and unseemly costume that could be imagined. They are, however, very inquisitive, and occasionally in bye-streets, one is able to get a good glance at them before they pull down their veils.

The dress of the citizens of Persia has been often described both by ancient and modern travelers. That of the men has changed very materially within the last century. The turban, as a head dress, is now worn by none but the Arabian inhabitants of that country. The Persians wear a long cap covered with lamb’s wool, the appearance of which is sometimes improved by being encircled with a cashmere shawl. The inhabitants of the principal towns are fond of dressing richly. Their upper garments are either made of chintz, silk, or cloth and are often trimmed with gold or silver lace; they also wear brocade, and in winter their clothes are lined with furs, of which they import a great variety. It is not customary for any person, except the king to wear jewels; but nothing can exceed the profusion which he displays of these ornaments; and his subjects seem peculiarly proud of this part of royal magnificence. They assert that when the monarch is dressed in his most splendid robes, and is seared in the sun, that the eye cannot gaze on the dazzling brilliancy of his attire.

Based on Hughes, Dictionary of Islam

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved