It is related that one of the Companions, named ‘Usman Ibn Maz’un, wished to lead a life of celibacy, but Muhammad forbad him.

The following are come of the sayings of Muhammad on the subject of marriage (see Mishkatu ‘l-Masibih, book xiii) :— “The best wedding is that upon which the least trouble and expense is bestowed.”

“The worst of feasts are marriage feasts, to which the rich are invited and the poor left out, and he who abandons the acceptation of en invitation, then verily disobeys God and His Prophet.”

“Matrimonial alliances (between two families or tribes) increase friendship more than anything else.”

Woman who will love their husbands and be very prolific, for I wish you will be more numerous than my other people.”

“When anyone demands your daughter in marriage, and you are pleased with his disposition and his faith, then give her to him; for if you do not so, then there will be strife and contention in the world.”

“A woman may be married either for her money, her reputation, her beauty, or her religion; then look out for a religious woman, for if you do marry other than a religious women, may your hands be rubbed with dirt”

“All young men who have arrived at the ago of puberty should marry, for marriage prevents sins. He who cannot marry should fast.”

“When a Muslim marries he perfects half his religion, and he should practice abstinence for the remaining half.”

“Beware! make not large settlements upon women; because, if great settlements were a cause of greatness in the world and of righteousness before God, surely it would be most proper for the Prophet of God to make them.”

“When any of you wishes to demand a woman in marriage, if he can arrange it, let him see her first.”

“A woman ripe in years shall have her consent asked in marriage, and if she remain silent her silence is her consent, and if she refuse she shall not be married by force.”

“A widow shall not be married until she be consulted, nor shall a virgin be married until her consent be asked.” The Companions said,” in what manner is the permission of virgin?” He replied, “Her consent is by her silence.”

“If a woman marries without the consent of her guardian, her marriage is null and void, is null and void, is null and void; then, if her marriage hath been consummated, the woman shall take her dower; if her guardians dispute about her marriage, then the king is her guardian.”

The subject of Muslim marriages will now be treated in the present article under the headings — I. The Validity of Marriage; II. The Legal Disabilities to Marriage; III. The Religious Ceremony; IV. The Marriage Festivities.

I. — The Validity of Marriage.

Muslims are permitted to marry four free women, and to have as many slaves for concubines as they may have acquired. See Qur’an, Surah iv. 8: “Of women who some good in your eyes, marry two, or three, or four; and if ye still fear that ye shall not act equitably, then one only; or the slave whom ye have acquired.” [WIVES.]

Usufructory or temporary marriages were sanctioned by the Prophet, but this law is said by use Sunnis to have been abrogated. although it is allowed by the Shi’ahs, and is practised in Persia in the present day. [MUT’AH.] Those temporary marriages are undoubtedly the greatest blot in Muhammad’s moral legislation, and admit of no satisfactory apology.

Marriage, according to Muslim law, is simply a civil contract, and its validity does not depend upon any religious ceremony. Though the civil contract is not positively prescribed to be reduced to writing, its validity depends upon the consent of the parties, which is called (izab and qabul, “declaration” and ” acceptance”; the presence of two male witnesses (or one male and two female witnesses); and a dower of not lees than ten dirhams, to be settled upon the woman. The omission of the settlement does not, however, invalidate the contract, for under any circumstances, the woman becomes entitled to her dower of ten dirhams or more. (a dower suitable to the position of the woman is called Mahru ‘l-misl.)

Liberty is allowed a woman who has reached the age of puberty, to marry or refuse to marry a particular man, independent of her guardian, who has no power to dispose of her in marriage without her consent or against her will; while the objection is reserved for the girl, married by her guardian during her infancy, to ratify or dissolve the contract immediately on reaching her majority. When a woman, adult and sane, elect to be married through an agent (wakil), she empowers him, in the presence of competent witnesses, to convey her consent to the bridegroom. The agent, if a stranger, need not see her, and it is sufficient that the witnesses, who see her, satisfy him that she, expressly or impliedly, consents to the proposition of which he is the bearer. The law respects the modesty of the sex, and allows the expression of consent on the part of the lady by indirect ways, even without words. With a virgin, silence is taken as consent, and so is a smile or laugh.

Mr. Syed Ameer Ali says:-

“The validity of a marriage under the Muslim law depends on two conditions: first, on the capacity of the parties to marry each other; secondly, on the celebration of the marriage according to the forms prescribed in the place where the marriage is celebrated, or when are recognised as legal by the customary law of the Mussalmans. It is a recognised principle that the capacity of each of the parties to a marriage is to be judged of by their respective lex domicilii. ‘If they are each, whether belonging to the same country or to different, countries, capable according to their lex domicilii of marriage with the other, they have the capacity required by the rule under consideration. In short, as in other contracts, so in that of marriage, personal capacity must depend on the law of domicile.’

“The capacity of a Mussalmen domiciled in England will be regulated by the English law, but the capacity of one who is domiciled in the Belad-ul-Islam (i.e. a Muslim country), by the provisions of the Mussalman law. It is, therefore, important to consider what the requisite conditions are to vest in an individual the capacity to enter into a valid contract of marriage. As a general rule, it may ho remarked, that under the Islamic law, the capacity to contract a valid marriage rests on the same basis as the capacity to enter into any other contract. ‘Among the conditions which are requisite for the validity of a contract of marriage (says the Fatawa-i-Alamgiri, p. 377), are understanding, puberty, and freedom, in the contracting parties, with this difference, that whilst the first requisite is essentially necessary for the validity of the marriage, as a marriage cannot be contracted by a majnun (non compos mentis), or a boy without understanding, the other two conditions are required only to give operation to the contract, as the marriage contracted by a (minor) boy (possessed) of understanding is dependent for its operation on the consent of his guardian.’ Puberty and discretion constitute, accordingly, the essential conditions of the capacity to enter into a valid contract of marriage. A person who is an infant in the eye of the law is disqualified from entering into any legal transactions (tassaruj’at–shariyeh–tasarrufat-i-shar’iah), and is consequently incompetent to contract a marriage. Like the English common law, however, the Muslim law makes a distinction between a contract made by a minor possessed of discretion or understanding and one made by a child who does not possess understanding. A marriage contracted by a minor who has not arrived at the age of discretion, or who does not possess understanding, or who cannot comprehend the consequences of the act, is a mere nullity.

“The Muslim law fixes no particular age when discretion should be presumed. Under the English law, however, the age of seven marks the difference between want of understanding in children and capacity to comprehend the legal effects of particular acts. The Indian Penal Code also has fined the age of seven as the period when the liability for offences should commence. It may be assumed, perhaps not without some reason, that the same principle ought to govern oases tinder the Muslim law, that is, when a contract of marriage is entered into by a child under the age of seven, it will be regarded as a nullity. It is otherwise, however, is, the case of a marriage contracted by a person of understanding. ‘It is valid, say, the Fatawa, ‘though dependent for its operation on the consent of the guardian.

“A contract entered into by a person who is insane is null and void, unless it is made during a void interval. A slave cannot enter into a contract of marriage without the consent of his master. The Mussalman lawyers, therefore, add freedom (hurriyet) as one of the conditions to the capacity for marriage.

“Majority is presumed, among the Hanafis and the Shiahs, on the completion of the fifteenth year, in the case of both males and females, unless there is any evidence to show that puberty was attained earlier.

“Besides puberty and discretion, the capacity to marry requires that there should be no legal disability or bar to the union of the parties; that in fact they should not be within the prohibited degree, or so related to or connected with each other as to make their union unlawful.” (See Syed Ameer Ali’s Personal Law off the Muslims, p. 216.)

With regard to the consent of the woman, Mr. Syed Ameer Ali remarks :—

“No contract can be said to be complete unless the contracting parties understand its nature and mutually consent to it. A contract of marriage also implies mutual consent, and when the parties see one another, and of their own accord agree to bind themselves, both having the capacity to do so, there is no doubt as to the validity of the marriage. Owing, however, to the privacy in which Eastern women. generally live, amid the difficulties under which they labour in the exercise of their own choice in matrimonial matters the Mohammadan law, with somewhat wearying particularity, lay down the principle by which they may not only protect themselves from the cupidity of their natura guardians, but may also have a certa scope in the selection of their husbands.

“For example, when a marriage is contracted on behalf of an adult person of either sex, it is an essential condition to the validity that such person should consent thereto, or in other words, marriage contracted without his or her authority or consent is null, by whomsoever it may have been entered into.

“Among the Hanafi and the Shiah., the capacity of a woman, who is adult and sane, to contract herself in marriage is absolute. The Shiah law is most explicit on this point. It expressly declares that, in the marriage of a discreet female (rashidah) who is adult, no guardian is required. The Hidaya holds the same opinion. A woman (it says) who is adult and of sound mind, may be married by virtue of her own consent, although the contract may not have been made or acceded to by her guardians, and this whether she be a virgin or saibbah. Among the Shafais and the Malikis, although the consent of the adult virgin is an essential to the validity of contract of marriage entered into on her behalf, as among the Hanafis and the Shiahs, she cannot contract herself in marriage without the intervention of a wali. (Hamilton’s Hidayah, vol. i. p. 95.)

“Among the Shafais, a woman canot personally consent to the marriage. The presence of the wali, or guardian, is essentially necessary to give validity to the contract. The wali’s intervention as required by the Shafais and the Maslikis to supplement the presumed incapacity of the woman to understand the nature of the contract, to settle the terms and other matters of a similar import, and to guard the girl from being victimised by an unscrupulous adventurer, or from marrying a person morally or socially unfitted for her. It is owing to the importance and multifariousness of the duties with which a wali is charged, that the Sunni law is particular in ascertaining the order in which the right of guardianship is possessed by the different individuals who may be entitled to it. The schools are not in accord with reference to the order. The Hanafis entrust the office first to the agnates in the order of succession; then to the mother, the sister, the relatives on the mother’s side, and lastly to the Kazi. The Shafais adopt the following order: The fattier, the father’s father, the son (by a previous marriage), the full brother, the consanguineous brother, the nephew, the uncle, the cousin, the tutor, and lastly the Kazi; thus entirely excluding the female relations from the wilayet. The Malikis agree with the Shafais in confiding the office of guardian only to men, but they adopt an order slightly different. They assign the first rank to the sons of the woman (by a former marriage), the second to the father: and then successively to the full brother, nephew, paternal grandfather. paternal uncle, cousin, manumittor, and lastly to the Kazi. Among the Malikis and the Shafais, where the presence of the guardian at a marriage is always necessary, the question has given birth to two different systems. The five; of these considers the guardian to derive his powers entirely from the law. It consequently insists not only on his presence at the marriage, but on his actual participation in giving the consent. According to this view, not only is a marriage contracted through a more distant guardian invalid, whilst one more nearly connected is present, but the latter cannot validate a marriage contracted at the time without his consent, by according his consent subsequently. This harsh doctrine, however, does not appear to be forced in any community following the Maliki or Shafai tenets. The second system is diametrically opposed to the first, and seems to have been enunciated by Shaikh: Ziad as the doctrine taught by Malik. According to this system the right of the guardian, though no doubt a creation of the law, is exercised only in virtue of the power or special authorization granted by the woman: for the woman once emancipated from the patria potestas is mistress of her own actions. She is not only entitled to consult her own interests in matrimony, but can appoint whomsoever she chooses to represent her and. protect her is legitimate interests. If she think the nears guardian inimically inclined towards her, she may appoint one more remote to act for he during her marriage. Under this view a the law, the guardian acts as an attorney on behalf of the woman. deriving all his powers from her and acting solely for her benefit., This doctrine has been adopted by Al-Karkhi, Ibn al-Kasim, and Ibn-i-Salamun and has been formally enunciated by the Algerian Kazis in several consecutive judgments. When the wali preferentially entitled to act is absent, and his whereabouts unknown, when he is a prisoner or has been reduced to slavery, or is absent more than ten days’ journey from the place where the woman is residing, or is insane or an infant, then the wilayet passes to the person next in order to him. The Hanafis hold that the woman is always entitled to give her consent without the intervention of a guardian. When a guardian is employed and found acting on her behalf, he is presumed to derive his power solely from her, so that he cannot act in any circumstances in contravention of his authority or instructions. When the woman has authorised her guardian to marry her to particular individual, or has consented to a marriage proposed to her by a specific person, the guardian has no power to marry her to another. Under the Shiah law, a woman who is ‘adult and discreet,’ is herself competent to enter into a contract of marriage. She requires no representative or intermediary, through whom to give her consent. ‘If her guardians,’ says the Sharaya, ‘refuse to marry her to an equal when desired by her to do so, there is no doubt that she is entitled to contract herself, even against their wish.’ The Shiahs agree with the Hanafis in giving to females the power of representing others in matrimonial contracts. In a contract of marriage, full regard is to be paid to the words of a female who is adult and sane, that is, possessed of sound understanding; she is, accordingly, not only qualified to contract herself, but also to act as the agent of another in giving expression either to the declaration or to the consent. The Mafátih and the Jama-ush-Shattat, also declare ‘that it is not requisite that the parties through whom a contract is entered into should both be males, since with us (the Shiahs) a contract made through (the agency or intermediation of) a female is valid.’ To recapitulate. Under the Maliki and Shafai law, the marriage of an adult girl is not valid unless her consent is obtained to it, but such concept must be given through a legally authorised wali who would act as her representative. Under the Hanafi and Shiah law, the woman can consent to her own marriage, either with or without a guardian or agent.” (Personal Law of the Muslims, p. 238.)

II.—The Legal Disabilities to Marriage.

There are nine prohibitions to marriage, namely:-

1. Consanguinity, which includes mother, grandmother, sister, niece, aunt, &c.

2. Affinity, which includes mother-in-law, step-grandmother, daughter-in-law, step-granddaughter, &c.

3. Fosterage. A man cannot marry his foster mother, nor foster sister, unless the foster brother and sister were nursed by the same mother at intervals widely separated. But a man may marry the mother of his foster sister, or the foster mother of his sister.

4. A man may not marry his wife’s sister during his wife’s lifetime, unless she be divorced.

5. A man married to a free woman cannot marry a slave.

6. It is not lawful for a man to marry the wife of mu’taddah of another, whether the ‘iddah be on account of repudiation or death. That is, he cannot marry until the expiration of the woman’s ‘iddah, or period of probation.

7. A Muslim cannot marry a polytheist, or Majusiyah. But he may marry a Jewess, or a Christian, or a Sabean.

8. A woman is prohibited by reason of property. For example, it is not lawful for a man to marry his own slave, or a woman her bondsman.

9. A woman is prohibited by repudiation or divorce. If a man pronounces three divorces upon a wife who is free, or two upon a slave, she is not lawful to him until she shall have been regularly espoused by another man, who having duly consummated the marriage, afterwards divorces her, or dies, and her ‘iddah from him be accomplished.

Mr. Syed Ameer Ali says:-

“The prohibitions may be divided into four heads viz. relative or absolute, prohibitive, or directory. They arise in the first place from legitimate and illegitimate relationship of blood (consanguinity); secondly, from alliance or affinity (al-musaharat); thirdly, from fosterage (ar-riza’); and fourthly, from completion of number (i.e. four). The ancient Arabs permitted the union of step-mothers and mothers-in-law on one side, and step-sons and sons-in-law on the other. The Kuran expressly forbids this custom: ‘Marry not women whom your fathers have had to wife (except what is already past), for this is an uncleanliness and abomination, and an evil way.’ (Surah iv. 26.) Then come the more definite prohibitions in the next verse: ‘Ye are forbidden to marry your mothers, your daughters, your sisters, your aunts, both on the father’s and on the mother’s side; your brother’s daughters and your sister’s daughters; your mothers who have given you suck, and your foster sisters; yours wive’s mothers, your daughters-in-law, born of your wives with whom ye have cohabited. Ye are also prohibited to take to wife two sisters (except what is already past) nor to marry women who are already married. (Surah iv. 27.)

“The prohibitions founded on consanguinity (tahrimu ‘n-nasab) are the same among the Sunnis as among the Shirahs. No marriage can be contracted with the ascendants, with the descendents, with relations of the second rank, such as brothers and sisters or their descendents, with paternal and maternal uncles and aunts. Nor can a marriage be contracted with a natural offspring or his or her descendents. Among the Shiahs, marriage is forbidden for fosterage in the same order as in the case of nasab. The Sunnis, however, permit marriage in spite of fosterage in the following cases: The marriage of the father of the child with the mother of his child’s foster-mother with the brother of the child whom she have fostered, the marriage With the foster-mother of an uncle or aunt. The relationship by fosterage arises among the Shiahs when the child has been really nourished at the breast of the foster-mother. Among the Sunnis, it is required that the child should have been suckled at least fifteen times, or at least a day and night. Among the Hanafis, it is enough if it have been suckled only once. Among the Shafais it is necessary that it should have been suckled four times. There is no difference among the Sunnis and the Shiahs regarding the prohibitions arising from alliance. Under the Shiah law, a woman against whom a proceeding by laan (li’an) has taken place on the ground of her adultery, and who is thereby divorced from her husband, cannot under any circumstance re-marry him. The Shaiais and Malikis agree in this opinion with the Shiahs. The Hanafis, however, allow a re-marriage with a woman divorced by laan. The Shiahs as well as the Shafias, Malikis, and Hanbalis, hold that a marriage with a woman who is already pregnant (by another) is absolutely illegal. According to the Hidaya, however, it would appear that Abu Hanifah and his disciple Muhammad were of opinion that such a marriage was allowable. The practice among the Indian Hanafis is variable. But generally specking, such marriages are regarded with extreme disapprobation. Among the Shafais, Malikis, and Hanbalis, marriages are prohibited during the state of ihram (pilgrimage to Makkah), so that when a marriage is contracted by two persons, either of whom is a follower of the doctrines of the above-mentioned schools whilst on the pilgrimage, it is illegal. The Hanafis regard such marriages to be legal. With the Shiahs, though a marriage in a state of ihram is, in any case, illegal, the woman is not prohibited to the man always, unless he was aware of the illegality of the union. All the schools prohibit contemporaneous marriages with two women so related to each other that, supposing either of them to be a male a marriage between them would be illegal. Illicit intercourse between a man and a woman, according to the Hanafis an Shiahs prohibits the man from marrying the woman’s mother as well as her daughter. The observant student of the law of the two principle sects which divide the world of Islam, cannot fail to notice the distinctive peculiarity existing between them in respect to their attitude to outside people. The nations who adopted the Shiah doctrines never seem to have come in contact with the Christian races of the West to any marked extent; whilst their relations with the Mago-Zoroastrians of the East were both intimate and lasting. The Sunnis, on the other hand, seem always to have been more or less influenced by Western nations. In consequence of the different positions which the followers of the sects occupied towards non-Muslims, a wide divergence exists between the Shiah and Sunni schools of law regarding intermarriages between Muslims and non-Muslims. It has already been pointed out that the Kuran, for political reasons, forbade all unions between Mussalmans and idolaters. It said in explicit terms, “Marry not a woman of the Polytheists (Mushrikin) until she embraces Islam.” But it also declared that ‘such women as are muhsinas (of chaste reputation) belonging to the scriptural sects,’ or believing in a revealed or moral religion, ‘are lawful to Muslims.’

“From these and similar directions, two somewhat divergent conclusions have been drawn by the lawyers of the two schools. The Sunnis recognise as legal and valid a marriage contracted between a Muslim on one side, and a Hebrew or a Christian woman on the other. They hold, however, that a marriage between a Mussalman and a Magian or a Hindu woman is invalid. The Akhbari Shiahs and the Mutazalas agree with the Sunni doctors. The Ursuli Shiahs do not recognise as legal a permanent contract of marriage between Muslims and the followers of any other creed. They allow, however, temporary contracts extending over a term of years, or a certain specified period, with a Christian, Jew, or a Magian female. Abu Hanifah permits a Mussalman to marry a Sabean woman, but Abu Yusuf and Muhammad and the other Sunni Imams, hold such unions illegal.

“A female Muslim cannot under any circumstances marry a non-Muslim. Both schools prohibit a Muslim from marrying an idolatrous female, or one who worships the stars or any kind of fetish whatsoever.

“These prohibitions are relative in their nature and in their effect. They do not imply the absolute nullity of the marriage. For example, when a Muslim marries a Hindu woman in a place where the laws of Islam are in force, the marriage only is invalid, and does not affect the status of legitimacy of the offspring.” (See Personal Law of the Muslimss, p. 220.)

III.—The Religious Ceremony.

The Muslim law appoints no specific religious ceremony, nor are any religious rites necessary for the contraction of a valid marriage. Legally, a marriage contracted between two persons possessing the capacity to enter into the contrast, is valid and binding, if entered into by mutual consent in the presence of witnesses. And the Shi’ah law even dispenses with witnesses.

In India there is little difference between the rites that are practiced at the marriage ceremonies of the Shi’ahs and Sunnis.

In all cases the religious ceremony is left entirely to the discretion of the Qazi or person who performs the ceremony, and consequently there is no uniformity of ritual. Some Qazis merely recite the Fatihah (the first chapter of the Qur’an), and the durud, or blessing. The following is the more common order of performing the service. The Qazi, the bridegroom, and the bride’s attorney, with the witnesses, having assembled in some convenient place (but not in a mosque), arrangements are made as to the amount of dower or mahr. The bridegroom than repeats after the Qazi the following:-

1. The Istighfar. I desire forgiveness from God.”

2. The four Quls. The four chapters of the Qur’an commencing with the word “Qul”. (cix., cxii, cxiii, cxiv.). These chapters have nothing in them connected with the subject of marriage, and appear to be selected on account of their brevity.

8. The Kalimah, or Creed. “There is no Deity hut God, and Muhammad is the Prophet of God.”

4. The Sifwatu ‘l—Iman A profession of belief in God, the Angels, the Scriptures, the Prophets, the Resurrection, and the Absolute Decree of good and evil.

The Qazi then requests the bride’s attorney to take the hand of the bridegroom, and to say, “Such an one’s daughter, by the agency of her attorney and by the testimony of two witnesses, has, in your marriage with her, had such a dower settled upon her; do you consent to it?” To which the bridegroom replies, “With my whole heart and soul, to my marriage with this woman, as well as to the dower already settled upon her, I consent, I consent, I consent.”

After this the Qazi raises his hands and offers the following prayer “O great God! grant that mutual love may reign between this couple, as it existed between Adam and Eve, Abraham and Sarah, Joseph and Zalikha, Moses and Zipporah, his highness Muhammad and ‘Ayishah, and his highness ‘Ali al-Murtaza and Fatimatu ‘z-Zahra.”

The ceremony being over, the bridegroom embraces his friends and receives their congratulations.

According to the Durru ‘l-Mukhtar, p. 196, and all schools of Muslim law, the bridegroom is entitled to see his wife before the marriage, but Eastern customs very rarely allow the exercise of this right, and the husband, generally speaking, sees his wife for the first thus when leading her to the nuptial chamber.

IV.—The Marriage Festivities.

Nikah is preceded and followed by festive rejoicings which have been variously described by Oriental travel1ers, but they are not parts of either-the civil or religious ceremonies.

The following account of a shadi or wedding in Hindustan is abridged (with some correction) from Mrs. Meer Hasan Ali’s Musalmans of India.

The marriage ceremony usually occupies three days and three nights. The .day being fixed, the mother of the bride actively employs the intervening time in finishing her preparations for the young lady’s departure from the paternal roof with suitable articles, which might prove the bride was not sent forth to her new family without proper provision: A silver-gilt bedstead with the necessary furniture; a silver pawn-dan, shaped, very like an English spice box; a chillumchi or wash-hand basin; a lota or water-jug, resembling an old-fashioned coffee-pot; a silver luggun, or spittoon a suraal, or water-bottle; silver basins for water; several dozens of copper pots; plates, and spoons for cooking; dishes; plates and platters in endless variety and numerous other articles needful for house-keeping, including a looking-glass for the bride’s toilette, masnads, cushions, and carpets.

On the first day the ladie’s apartments of both houses are completely filled with visitors of all grades, from the wives and mothers of noblemen, down to the humblest acqnaintance of the family, and to do honour to the hostess, the guests appear in their best attire and most valuable ornaments. The poor bride is kept in strict confinement in a dark closet or room during the whole three days’ merriment, whilst the happy bridegroom is the most prominent person in the assembly of the males, where amusements are contrived to please and divert him, the whole party vying in personal attentions to him. The ladies are occupied in conversations and merriment and amused with native songs and music of the domain, smoking the buqqa, eating pawn, dinner, &c. Company is their delight and time passes pleasantly with them in such an assembly.

The second day is one of bustle and preparation in the bride’s home; it is spent in arranging the various articles that are to accompany the bride’s mayndi or hinna (the Lawsonia inervis), which is forwarded in the evening to the bridegroom’s house with great parade. The herb mayndi or henna is in general request amongst the natives of India, for the purpose of dyeing the hands and feet; and is considered by them an indispensable article to their comfort, keeping those members cool, and a great ornament to the person. Long established custom obliges the bride to send mayndi on the second night of the nuptials to the bridegroom; and to make the event more conspicuous, presents proportioned to the means of the party accompany the trays of prepared mayndi.

The female friends of the bride’s femur attend the procession in covered conveyances, and the male guests on horses, elephants, and in palkies; trains of servants and bands of music swell the procession (amongst persons of distinction) to a magnitude inconceivable to those who have not visited the large native cities of India.

Amongst the bride’s presents with mayndi may be noticed everything requisite for a fell-dress suit for the bridegroom, and the etcetras of his tollette; confectionary, dried fruits, preserves, the prepared pawns, and a multitude of trifles too tedious to enumerate, but which are nevertheless esteemed luxuries with the native young people, and are considered essential to the occasion. One thing I must not omit, the sugar candy, which forms the source of amusement when the bridegroom is under the dominion of the females in his mother’s zananah. The fire-works sent with the presents are concealed in flowers formed of the transparent uberuck; these flowers are set out in frames, and represent beds of flowers in their varied forms and colors, these in their number and gay appearance have a pretty effect in the procession, interspersed with the trays containing the dresses, &c. All the trays are first covered with basketwork raised in domes, and over these are thrown draperies, neatly fringed in bright colors. The mayndi procession having reached the bridegroom’s house, bustle and excitement pervade through every department of the mansion. The gentlemen are introduced to the father’s hall; the ladies to the youth’s mother, who in all possible state is prepared to recetye the bride’s friends.

The, ladies crowd into the centre hall to witness through the blinds of bamboo, the important process, of dressing the bridegroom in his bride’s presents. The centre purdah is let down, in which are opening to admit the hands and feet: and close to thin purdah a low stool is placed. When all these preliminary preparations are made and the ladies securely under cover, notice is sent to the male assembly that “the bridegroom is wanted”; and he then enters the zananah courtyard, amidst the deafening sounds of trumpets and drums from without, and a serenade from the female singers within. He seats himself on the stool planed for him close to the purdah, and obeys the several commands he receives from the hidden females, with childlike docility. The moist mayndi is then tied on with bandage by hands he cannot see and, if time admits, one hour is requisite to fix the dye bright and permanent on the hands and feet. During this delay, the hour is passed in lively dialogues with the several purdahed dames, who have all the advantages of seeing though themselves unseen; the singers occasionally lauding his praise in extempore strains, after describing the loveliness of his bride (whom they know nothing about), and foretelling the happiness which awaits him in his marriage, but which, in the lottery, may perhaps prove a blank. The sugar-candy, broken into small lumps, is presented by the ladles whilst his hands and feet are fast bound in the bandages of mayndi, but as be cannot help himself, and it is an omen of good to eat the bride’s sweets at this ceremony, they are sure he will try to catch the morsels which they present to his mouth and then draw back, teasing the youth with their bantering, until at last he may successfully snap at the candy, and seize the fingers also with the dainty, to the general amusement of the whole party and the youth’s entire satisfaction.

The mayndi supposed to have done its duty the bandages are removed, the old nurse of his infancy (always retained for life), assists him with water to wash off the leaves, dries his feet and hands, rubs him with perfume, and robes him in his bride’s present.. Thus attired, he takes leave of his tormentors, sends respectful messages to his bride’s family, and bows his way from their guardianship to the male apartment, where he is greeted by a flourish of trumpets and the congratulations of the guests, many of whom make him presents and embrace him cordially.

The dinner is introduced at twelve, amongst the bridegroom’s guests, and the night passed in good-humoured conviviality, although the strongest beverage at the feast consists of sugar and water sherbet, the dancing- women’s performances, the displays of fire-works, the dinner, pawn, and huqqah, form the chief amusements of the night, and they break up only when the dawn of morning approaches.

The bride’s female friends take sherbet and pawn after the bridegroom’s departure from the zananah, after which they hasten away to the bride’s assembly, to detail the whole business of their mission.

The third day, the eventful barat, arrives to awaken in the heart of a tender mother all the good feelings of fond affection; she is, perhaps, about to part with the great solace of her life under many domestic trials; at any rate, she transfers her beloved child to another protection. All marriages are not equally happy in their termination; it is a lottery, a fate, in the good mother’s calculation. Her darling child may be the favoured of heaven, for which she prays; she may be however, the miserable first wife of a licentious pluralist; nothing is certain, but she will strive to trust in God’s mercy, that the event prove a happy one to her dearly-loved girl.

The young bride is in close confinement during the days of celebrating her nuptials; on the third, she is tormented with the preparations for her departure. The mayndi must be applied to her hands and feet, the formidable operations of bathing, drying her hair oiling and dressing her head, dyeing her lips, gums, and teeth with antimony, fixing on her the wedding ornaments, the nose-ring presented by her husband’s family; the many rings to be placed on her fingers and toes, the rings fixed in her ears, are all so many new trials to her, which though a complication of inconvenience she cannot venture to murmur at, and therefore submits to with the passive weakness of a lamb.

Towards the close of the evening, all these preparations being fulfilled, the marriage portion is set in order to accompany the bride. The guests make their own amusements for the day: the mother is too much occupied wish her daughter’s affairs to give much of her time or attention to them; nor do they expect it, for they alt know by experience the nature of a mother’s duties at such an interesting period.

The bridegroom’s house is nearly in the same state of bustle as the bride’s, though of a very different description, as the preparing for the reception of a. bride is an event of vast importance in the opinion of a Musalman. The gentlemen assemble in the evening, and are regaled with sherbet and the huqqah, and entertained with the nauch-singing and fire-works, until the appointed hour for setting out in the procession to fetch the bride to her new home.

The procession is on a grand scale every friend or acquaintance, together with their elephants, are pressed into the service of the bridegroom on this night of Barat. The young man himself is mounted on a handsome charger the legs, tail, and mane of which are dyed with mayndi, whilst the ornamental furniture of the horse is splendid with spangles and embroidery. The dress of the bridegroom is of gold cloth, richly trimmed, with a turban to correspond to the top of which is fastened an immense bunch of silver trimming, that falls over his face to his waist, and answers the purpose of a veil (this is in strict keeping with the Hindu custom at their marriage processions). A select few of the females from the bridegroom’s house attend in his train to bring home the bride, accompanied by innumerable torches, with bands of music, soldiers, and servants, to give effect to the procession. On their arrival at the gate of the bride’s residence, the gentlemen are introduced to the father’s apartments, where fire-works, music, and singing, occupy their time and attention until the hour for departure arrives.

The marriage ceremony is performed in the presence of witnesses, although the bride is not seen by any of the males at the time, not even by her husband, until they have been lawfully united according to the common form.

The Maulawi commences by calling on the young maiden by name, to answer to his demand, ‘It is by your own consent this marriage takes place with —?” naming the person who is the bridegroom; the bride answers,” It is by my consent.” The Maulawi then explains the law of Muhammad, and reads a certain chapter from that portion of the Qur’an which binds the parties in holy wedlock. He then turns to the young man, and asks him to name the sum he proposes as his wife’s dowry. The bridegroom thus called upon, names ten, twenty, or perhaps, a hundred lacs of rupees; the Maulawi repeats to all present the amount proposed, and then prays that the young couple thus united may be blessed in this world and in eternity. All the gentlemen then retire except the bridegroom, who is delayed entering the hall until the bride’s guests have retreated into the side rooms; as soon as this is accomplished he is introduced into the presence of his mother-in-law and her daughter by the women servants. He studiously avoids looking up at he enters the hall, because, according to the custom of this people, he must first see his wife’s face in a looking—glass, which is placed before the young couple, when he is seated an the masnad by his bride. Happy for himself he then beholds a face that bespeaks the gentle being he hopes fate has destined to make him happy. If otherwise, he must submit; there is no untying the sacred contract.

Many absurd. customs follow this first introduction of the bride and bridegroom. When the procession is all formed, the goods and chattels of the bride are loaded on the heads of the carriers; the bridegroom conveys his young wife in his arms to the covered palankeen, which is in readiness within the court, and the procession moves off in grand style, with a perpetual din of noisy music, until they arrive at the bridegroom’s mansion.

The poor mother has, perhaps, had many struggles with her own heart to save her daughter’s feelings during the preparation for departure; but when she separation takes place, the scene is affecting beyond description. I never witnessed anything equal to it in other societies; indeed, so powerfully are the feelings of the mother excited, that she rarely acquires her usual composure until her daughter is allowed to revisit her, which is generally within a week after. her marriage. (See Mrs. Meer Hasan Ali’s Indian Musalmans, vol. 1. p. 46.)

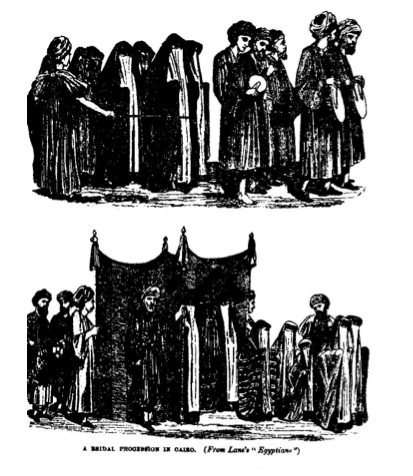

The above description of a wedding in India has been selected as representative of such ceremonies; but there is no uniform custom of celebrating Muslim nuptials, the nuptial ceremonies in Afghanistan being much more simple in their character, as will be seen by the illustration given on the preceding page.

Mr. Lane, in his Modern Egyptians, gives the following interesting account of a wedding in Egypt:-

“Marriages in Cairo are generally conducted, in the case of a virgin, in the following manner; but in that of a widow, or a divorced, woman, wilth little ceremony. Most commonly, the mother, or some other near female relation, of the youth or man who is desirous of obtaining a wife, describes to him the personal and other qualifications of the young women with whom she is acquainted, and directs his choice; or he employs ‘khat’beh’ or ‘khatibeh’ (khatibah) a, woman whose regular business it is to assist men in such cases. Sometimes two or more women of this profession are employed. A khat’beh gives her report confidentially, describing one girl as being like a gazelle, pretty and elegant and young; and another as not pretty, but rich, and so forth. If the man have a mother and other near female relations, two or three if these usually go with s khat’beh to pay visits to several harems, to which she has access in her professional character of a matchmaker; for she is employed as much by the women as the man. She sometimes, also, exercises the trade of a ‘dellaleh’ (or broker), for the sale of ornaments, clothing, &c., which procures her admission into almost every harem. The women will accompany her in search of a wife for their relation, are introduced to the different harems merely as ordinary visitors; and as such, if disappointed they soon take their leave, though the object of their visit is of course well understood by the other party, but if they find among the females of a family “and they are sure to see all who are marriageable a girl or young woman having the necessary personal qualifications, they state the motives of their visit, and ask, if the proposed match be not at once disapproved of, what property, ornaments, &c., the objects of their wishes may possess. If the “father of the intended bride be dead, she may perhaps possess one or more houses shops, &c.; and in almost every case a marriageable girl of the middle or higher ranks has a set of ornaments of gold and jewels. The women visitors having asked these and other question bring their report to the expectant youth or man. If satisfied with their report, he gives a present to the khat’beh, and sends her again to the family of his intended wife, to make known to them his wishes. She generally gives an exaggerated description of his personal attractions, wealth, &c. For instance, she will say of a very ordinary young man, of scarcely any property, and of whose disposition she knows nothing. ‘My daughter, the youth who wishes to marry you is young, graceful, elegant, beard-less, has plenty of money, dresses handsomely, is fond of delicacies, but cannot enjoy his, luxuries alone; he wants you as his companion; be will give you everything that money can procure; he is a stayer at home, and will spend his whole time with you, caressing and fondling you.’

“The parents may betroth their daughter to whom they please, and marry her to him without her consent, if she be not arrived at the age of puberty; but after she has attained that age, she may choose a husband for herself, and appoint any man to arrange and effect her marriage. In the former case how ever, the khat’beh and the relations of a girl sought in marriage usually endeavoar to obtain her consent to the proposed union. Very often a father objects to giving a daughter in marriage to a man who is not of the same profession or trade as himself; and to marrying a younger daughter before an elder! The bridegroom can scarcely over obtain even a surreptitious glance at the features of his bride, until he finds her in his absolute possession. Possession, unless she belong to the lower classes of society; in which case it is easy enough for him to see her face.

‘When a female is about to marry, she should have a ‘wakeel’ (wakil, or deputy) to settle the compact and conclude the contract, for her, with her proposed husband. If she be under the age of puberty, this is absolutely necessary; and in this case, her father, if living, or (if he be dead) her, nearest adult male relation, or a guardian appointed by will, or by the Kadee, performs the office of wakeel; but if she be of age, the appoints her own wakeel, or may even make the contract herself; though this is seldom done.

“After a youth or man has made choice of a female to demand in marriage, on the record of his female relations or that of the khat’beh, and, by proxy, made the preliminary arrangements before described with her and her relations in the harem, he repairs with two or three of his friends to her wakeel. Having obtained the wakeel’s consent to the union, if the intended bride be under age, he asks what is the amount of the required mahr (or dowry).

“The siring of a dowry is indispensable. The usual amount of the dowry, if the par-ties be in possession of a moderately good income, is about a thousand riyals (or twenty-two pounds ten shillings); or, sometimes, not more than half that sum. The wealthy calculate the dowry in purses of five hundred plasters (about five pounds sterling) each; and fix its amount at ten purses or more.

“It must be borne in mind that we are considering the case of a virgin bride; the dowry of a widow or divorced woman is much less. In settling the amount of the dowry, as in other pecuniary transactions, a little haggling frequently takes place; if a thousand riyals be demanded through the wakeel, the party of the intended bridegroom will probably make an offer of six hundred: the former party then gradually lowering the demand, and the other increasing the offer, they at length agree to fix it at eight hundred. It in generally stipulated that two-thirds of the down shall be paid immediately before the marriage contract is made; and the remaining third held in reserve, to be paid to the wife in case of divorcing her against her own consent, or in case of the husband’s death.

“This affair being settled, and confirmed by all persons present reciting the opening chapter of the Kuran (the Fat’hah), an early day (perhaps the day next following) is appointed for paying the money, and performing the ceremony of the marriage-contract, which is properly called ‘akd en-nikah’ (‘aqdu ‘n-nikah). The making this contract is commonly called ketb el-kitab’ (katbu ‘l-kitab, or the writing of the writ); but it is very seldom the ease that any document is written to confirm the marriage, unless the bridegroom is about to travel to another place, and fears that he may have occasion to prove his marriage where witnesses of the contract cannot be procured. Sometimes the marriage contract is concluded immediately after the arrangement respecting the dowry, but more generally a day or two after.

“On the day appointed for this ceremony, the bridegroom again accompanied by two or three of his friends, goes to the house of his bride, usually about noon, taking with him that portion of the dowry which he has promised to pay on this occasion. He and his companions are received by the bride’s wakeel, and two or more friends of the latter are usually present. It is necessary that there be two witnesses (and those must be Muslims) to the marriage-contract, unless in a situation where witnesses cannot be procured. All persons present recite the Fat’hah and the bridegroom then pays the money. After this, the marriage-contract is performed. It is very simple. The bridegroom and the bride’s wakeel sit upon the ground. face to face, with one knee upon the ground, and grasp each other’s right hand, raising tie thumbs, and pressing them against each other. A fekeeh (faqih) is generally employed to instruct them what they are to say. Having placed a handkerchief over their joined hands, he usually prefaces the words of the contract with a khutbeh (khutbah), consisting of a few words of exhortation and prayer, with quotations from the Kuran and Traditions, on the excellence and advantages of marriage. He then desires the bride’s wakeel to say, ‘I betroth (or marry) to thee my daughter (or the female who has appointed me her wakeel), such a one (naming the bride), the virgin (or the adult.), for a dowry of such an amount.’ (The words ‘for a dowry,’ &c., are sometimes omit’ -) The bride’s wakeel having said them the bridegroom says, ‘I accept from thee hot betrothal [or marriage] to myself, and take her under my care, and myself to afford her my protection; and ye who are present bear witness of this.’ The wakeel addressee the bridegroom in the same manner a second and a third time; and each time, the latter replies as before. Both then generally add, ‘And blessing be on the Apostles; and praise be to God, the Lord of the beings of the whole world. Amen.’ After which all present again repeat the Fat’hah. It is not always the same form of khutbeh that is recited on those occasions: any form may be used, and it may be repeated by any person it is not even necessary, and is often altogether omitted.

“The contract concluded, the bridegroom sometimes (but seldom, unless he be a person of the lower orders) kisses the hands of his friends and others there present; and they are presented with sharbat, and generally remain to dinner. Each of them receives an embroidered handkerchief, provided by the family of the bride; except the fekeeh, who receives a similar handkerchief, with a small gold coin tied up in it, from the bridegroom. Before the persons assembled on this occasion disperse, they settle when the ‘leylet ed-dakbleh’ is to be. This is the night when the bride is brought to the house of the bridegroom, and the latter, for the first time, visits her.

“The bridegroom should receive his bride on the eve of Friday, or that of Monday; but the foremer is generally esteemed the more fortunate period. Let us say, for instance, that the bride is to be conducted to him on the eve of Friday.

“During two or three or more preceding nights, the street or quarter in which the bridegroom lives is illuminated with chandeliers and lanterns, or with lanterns and small lamps, some suspended from cords drawn across from the bridegroom’s and several other houses on each side to the houses opposite; and several small silk flags, each of two colours, generally red and green, are attached to these or other cords.

“Art entertainment is also given on each of these nights, particularly on the last night before that on which the wedding is concluded, at the bridegroom’s house. On these occasions, it is customary for the persons invited, and for all intimate friends, to send presents to his home, a day or two before the feast which they purpose or expect to attend. They generally send sugar, coffee, rice, wax candles, or a lamb. The former articles are usually placed upon a tray of copper or wood, and covered with a silk or embroidered kerchief. The guests are entertained on these occasions by musicians and male or female singers, by dancing girls, or by the performance of a ‘khatmeh’ (khatmah), or ‘zikr’ (zikr).

“The customs which I am now about to describe are observed by those classes that compose the main bulk of the population of Cairo.

“On the preceding Wednesday (or on the Saturday if the wedding be to conclude on the eve of Monday), at about the hour of noon, or a little later, the bride goes in state to the bath.. The procession to the bath is called. ‘Zeffet el-Harmmam.’ It is headed by a party of musicians, with a hautboy or two, and drums of different kinds. Sometimes at the head of the bride’s party, are two men, who carry the utensils and linen used in the bath, upon two round trays, each of which is covered with an embroidered or a plain silk kerchief; also a sakka (saqqa) who gives water to any of the passengers, if asked; and two other persons, one of whom bears a ‘kamkam,’ or bottle, of plain or gilt silver, or of china, containing rose-water, or orange-flower water, which he occasionally sprinkles on the passengers; and the other, a ‘mibkharah’ (or perfuming vessel) of silver, with aloes-wood, or some other odoriferous substance, burning in it; but it is seldom that the procession is thus attended. In general, the first persona among the bride’s party are several of her married female relations and friends, walking in pairs;. and next, a number of young virgins. The former are dressed in the usual manner, covered with the black silk habarah; the latter have white silk habarahi, or shawls. Then follows the bride, walking under a canopy of silk of some gay colour, as pink, rose-colour, or yellow; or of two colours, composing wide stripes, often rose-colour and yellow. It is earned by four men, by means of a pole at each corner, and is open only in front; and at the top of each of the four poles is attached an embroidered handkerchief.

“The dress of the bride, during this procession, entirely conceals her person. She is generally covered from head to foot with a red kashmere shawl or with a white or yellow shawl, though rarely. Upon her head is placed a small pasteboard cap, or crown. The shawl is placed over this, and conceals from the view of the public the richer articles of her dress, her face, and her jewels, &c., except one or two kussaha’ (and sometimes other ornaments), generally of diamonds and emeralds, attached to that part of the shawl which covers her forehead.

“She is accompanied by two or three of her female relations within the canopy; and often, when in hot weather, a woman, walking backwards before her, is constantly employed in fanning her, with a large fan of black ostrich-feathers, the lower pare of the front of which is usually ornamented with a piece of looking-glass. Sometimes one zaffeh, with a single canopy, serves for two brides, who walk side by side. The procession moves very slowly, and generally pursues a circuitous route, for the sake of greater display. On leaving the house, it turns to the fight. It is closed by a second party of musicians similar to the first, or by two or three drummers.

“In the bridal processions of the lower orders, which are often conducted in the same manner as that above described, the women of the party frequently utter, at intervals, those shrill cries of joy called ‘zaghareet’; and females of the poorer classes, when merely spectators of a zeffeh, often do the earns. The whole bath is sometimes hired for the bride and her party exclusively.

“They pass several hours, or seldom less than two, occupied in washing, sporting, and feasting; and frequently ‘al-mehs,’ or female singers, are hired to amuse them in the bath; they then return in the same order in which they came.

“The expense of the zeffeh falls on the relations of the bride, but, the feast that follows it is supplied by the bridegroom.

“Having returned from the bath to the house of her family, the bride and her companions sup together. If ‘almehs have contributed to the festivity in the bath., they, also, return with the bride, to renew their concert. Their songs are always on the subject of love, and of the joyous event which occasions their presence. After the company have been thus entertained, a large quant of henna having been prepared, mixed into a paste, the bride takes a lump of it in her hand, and receives contributions (called ‘nukeet’) from her guests; each of them sticks a coin (usually of gold) in the hennsa which she holds upon her hand, and when the lump is closely stuck with these coins, she scrapes it off her hand upon the edge of a basin of water. Having collected in this manner from all her guests, some more henna is applied to her hands and feet, which are then bound with pieces of linen; and in this state they remain until the next morning, when they are found to be sufficiently dyed with its deep orange red tint. Her guests make use of the remainder of the dye for their own hands This night is called ‘Leylet el-Henna.’ or, ‘the Night of the Henna.’

“It is on this night, and sometimes also during the latter half of the preceding day that the bridegroom gives his chief entertainment.

Mobobbazeen’ (or low farce-players) often perform on this occasion before the house, or, if it be large enough in the court.

The other and more common performances by which the guests are amused, have been before mentioned.

“On the following day, the bride goes in procession to the house of the bridegroom. The procession before described is called ‘the zeffeh of the bath,’ to distinguish it from this, which is the more important, and which is therefore particularly called ‘Zeffeh al-‘Arooseh,’ or ‘the Zeffeh of the Bride’ In some tame, to diminish the expenses of the marriage ceremonies, the bride is conducted privately to the bath, and only honoured with a zeffeh to the bridegroom’s house. This procession is exactly similar to the former. The bride and her party, after breakfasting together, generally set out a little after midday. “They proceed in the same order, and at the same slow pace, as in the zeffeh of the bath; and. if the house of the bridegroom is near, thee follow a circuitous route, through several principal streets, for the sake of display. The ceremony usually occupies three or more hours.

“Sometimes, before bridal processions of this kind, two swordsmen, clad in nothing but their drawers, engage each other in a mock combat; or two peasants cudgel each other with nebboots or Long staves. In the procession of a bride of a wealthy family, any person who has the art of performing some extraordinary feat to amuse the spectators is almost sure of being a welcome assistant, and of receiving a handsome present. ‘When the Seyyid Omar, the Nakeel el-Ashraf (or chief of the descendants of the Prophet), who was the ream instrument of advancing Mohammad Alec to the dignity of Basha of Egypt, married a daughter about forty-five years since, there walked before the procession a young man who had made an incision in his abdomen, and drawn one a large portion of his intestines, which he carries before him on a silver tray. After the procession he restored them to their proper place, and remained in bed many days before he recovered from the effects of this foolish and disgusting act. Another man, on the same occasion, ran a swere through his arm, before the crowding spectators, and then bound over the wound, without withdrawing the sword, several handkerchiefs, which were soaked with the blood. These facts were described to me by an eye witness. A spectacle of a more singular and more disgusting nature used to be not uncommon on similar occasions, but is now very seldom witnessed. Sometimes, also, ‘hawees’ (or conjurors and sleight of hand performers) exhibit a variety of tricks on these occasions. But the most common of all the performances here mentioned are the mock fights. Similar exhibitions are also sometimes witnessed on the occasion of a circumcision. Grand zeffehs are, sometimes accompanied by a numbers of cars, each bearing a group of persons of some manufacture or trade, performing the usual work of their craft; even such as builders, whitewashers &c., including member, of all, or almost all, the arts and manufacture practised in the metropolis. In one car there are generally some men making coffee which they occasionally present to spectators in another, instrumental musicians, and in another, ‘al’mehs (or female singers).

“The bride, in zeffehs of this kind, is sometimes conveyed in a close European carriage, but more frequently, she and her female relations and friends are mounted on high-saddled asses, and, with musicians and female singers, before and behind them, close the procession.

“The bride and her party having arrived at the bridegroom’s house, sit down to a repast. Her friends shortly after take their departure, leaving with her only her mother and sister, or other near female relations, and one or two other women; usually the belláneh. The ensuing night is called ‘Leylet ed-Dakhleh,’ or ‘the Night of the Entrance.’

“The bridegroom site below. Before sunset he goes to the bath, and there changes his clothes, or he merely does the latter at home; and, after having supped with a party of his friends, waits till a little before the night prayer, or until the third or fourth hour of the night, when, according to general custom, he should repair to some celebrated mosque, and there say his prayers. If young, he is generally honoured with a zeffeh on this occasion. In this case he goes to the mosque preceded by musicians with drums and a hautboy or two, and accompanied by a number of friends, and by several men bearing ‘mashals’ (mash’al). The mashals are a kind of cresset, that is, a staff with a cylindrical frame of iron at the top, filled with flaming wood, or having two, three, four, or five of these receptacles for fire. The party usually proceeds to the mosque with a quick pace, and without much order. A second group of musicians, with the same instruments, or with drums only, closes the procession.

“The bridegroom is generally dressed in a kuftan with red stripes, and a red gibbeh, with a kashmers shawl of the same colour for his turban, and walks between two friends similarly dressed. The prayers are commonly performed merely as a matter of ceremony, and it is frequently the ease that the bridegroom does not pray at all, or prays without having previously performed the wudoo like memlooks, who say their prayers only because they fear their master. The procession returns from the mosque with more order and display, and very slowly; perhaps because it would be considered unbecoming in the bridegroom to hasten home to take possession of his bride, it is headed, as before) by musicians, and two or more bearers of mashals. These are generally followed by two men, beaming, by means of a pole resting horizontally upon their shoulders, a hanging frame, to which are attached about sixty or more small lamps, in four circles, one above another, the uppermost of which circles is made to revolve, being turned round occasionally by one of the two bearers. These numerous before mentioned, brilliantly illumine the streets through which the procession passes, and produce a remarkably picturesque effect. The bridegroom and his friends and other attendants follow, advancing in the form of an oblong ring, all facing the interior of the ring, and each bearing in his hand one or more wax candles, and sometimes a sprig of henna, or some other flower, except the bridegroom and the friend on either aide of him. These three form the latter part of the ring, which generally consists of twenty or more persons.

“At frequent intervals, the party stops for a few minutes, and during each of the pauses, a boy or a man, one of the persons who compose the ring, sings a few words of an epithalamium. The sounds of the drums, and the shrill note of the hautboy (which the bride hears half an hour or more before the procession arrives at the house), cease during these songs. The train is closed, as in the former case (when on the way to the mosque) by a second group of musicians.

“In the manner above described, the bridegroom’s zeffeh is most commonly conducted; but there is another mode that is more respectable, called ‘zeffeh sádatee,’ which signifies the ‘gentlemen’s zeffeh.’ In this, the bridegroom is accompanied by his friends in the manner described above, and attended and preceded by man bearing mashals, hut not by musicians; in the place of these are about six or eight men, who, from their being employed as singers on occasions of this kind, are called ‘wilad el-layalee,’ or ‘sons of the nights. Thus attended, he goes to the mosque; and while he returns slowly thence to his house, the singers above mentioned chant, or rather sing, ‘muweshshahs’ (lyric odes) in praise of the Prophet. Having returned to the house, these same persons chant portions of the Kuran, one after another, for the amusement of the guests; then, all together, recite the opening chapter (the Fathah); after which, one of them sings a ‘kaseedeh’ ‘ (or short poem), in praise of the Prophet lastly, all of thorn again sing musweshahahs. After having thus performed, they receive ‘nukoot’ (or contributions of money) from the bridegroom and his friends.

“Soon after his return from the mosque, the bridegroom leaves his friends in a lower apartment, enjoying their pipes and coffee and sharbat. The bride’s mother and sister, or whatever other female relations were left with her, are above, and the bride herself and the belláneh, in a separate apartment. If the bridegroom is a youth or young man, it is considered proper that he as well as the bride should exhibit some degree of bashfulness; one of his friends, therefore, carries him a part of the way up to the hareem. Sometimes, when the parties are persons of wealth, the bride is displayed before the bridegroom in different dresses, to the number of seven; but generally he finds her with the belláneh alone, and on entering the apartment he gives a present to this attendant, “The bride has a shawl thrown over her head, and the bridegroom must give her a present of money, which is called ‘the price of the uncovering of the face, before be attempts to remove this, which she does not allow him to do without same apparent reluctance, if not violent resistance, in order to show her maiden modesty. On removing the covering, he says, ‘In the name of God, the Compassionate, the Merciful,’ and then greets her with this compliment: ‘The night be blessed,’ or ‘ — is blessed,’ to which she replies, If timidity do not choke her utterance, ‘God bless thee! The bridegroom now, in most cases, sees the face if his bride for the first time, and generally finds her nearly what he has been led to expect. Often, but not always, a curious ceremony is then performed.

“The bridegroom takes off every article of the bride’s clothing except her shirt, seats her upon a mattress or bed, the head of which is turned towards the direction of Makkah, placing her so that her back is also turned in that direction, and draws forward and spreads upon the bed, the lower part of the front of her shirt; having done this, he stands at the distance of rather less than three feet before her, and performs the prayers of two rak’ahs laying his head and hands in prostration upon the part of her shirt that is extended before her lap. He remains with her but a few minutes longer. Having satisfied his curiosity respecting her personal charms, he calls to the women (who generally collect at the door, where they wait in anxious suspense) to raise their cries of joy, or zaghareet, and the shrill sounds make known to the persons below and in the neighbourhood, and often, responded to by other women, spread still further the news that he has acknowledged himself satisfied with his bride. He soon after descends to rejoin his friends, and remains with them an hour, before he returns to his wife. It very seldom happens that the husband, if disappointed in his bride, immediately disgraces and divorces her; in general, he retains her in this case a week or more.

“Marriages, among the Egyptians, are sometimes conducted without any pomp or ceremony, even in the case of virgins, by mutual consent of the bridegroom and the bride’s family, or the bride herself; and widows and divorced women are never honoured with a zeffeh on marrying again. The mere sentence, ‘I. give myself up to thee,’ uttered by a female to a man who proposes to become her husband (even without the presence of witnesses, if none can easily be procured), renders her his legal wife, if arrived at puberty; and marriages with widows and divorced women, among the Muslims of Egypt, and other Arabs, are sometimes concluded in this simple manner. The dowry of widows and divorced women is generally one quarter or third or half the amount of that of a virgin.

“In Cairo, among persons not of the lowest order, though in very humble life, the marriage in conducted in the same manner as among the middle orders. But when the expenses of inch zeffehs as I have described cannot by any means be paid, the bride in paraded in a very simple manner, covered with a shawl (generally red), and surrounded by a group of her female relations and friends, dressed in their best, or in borrowed clothes, and enlivened by no other sounds of joy than their zaghareet, which they repeat at frequent intervals.” (Lane’s Modern Egyptians.)

(For the law of marriage in Hanafi law, see Fatawa-i-‘Alamgiri p. 377; Fatawa-i-Qazi Khan, p. 380; Hamiton’s Hidayah, vol. i. p. 89; Durru ‘l-Mukhtu, p. 196. In Shi’ah law, Jami’u ‘sh-Shattat; Shara’i’ l’-Islam, p. 260. For marriage ceremonies, Lane’s Egyptians; Herklott’s Musalmans; Mrs. Meer Hasan Ali’s Musalmans; M.C. de Perceval, His. des Arabes.)

Based on Hughes, Dictionary of Islam

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved