Lit. “That which is forbidden.” Anything sacred. (1) The first month of the Muslim year [MONTHS.]. (2) The first ten days of the month, observed in commemoration of the martyrdom of al-Husain, the second son of Fatimah, the Prophet’s daughter by ‘Ali. [AL-HUSAIN.] These days of lamentation are mainly observed by the Shi’ah Muslims, but the tenth day of Muharram is observed by the Sunnis in commemoration of its having been the day on which Adam and Eve, heaven and hell, the pen, fate, life and death, were created. [ASHURA’.]

The ceremonies of the Muharram differ much in different places and countries. The following is a graphic description of the observance of the Muharram at Ispahan in the year 1811, which has been taken, with some slight alterations from Morier’s Second Journey through Persia :—

The tragical termination of al-Husain’s life, commencing with his flight from al-Madinah and terminating with his death on the plain of Karbala’, has been drawn up in the form of a drama, consisting of several parts, of which one is performed by actors on each successive day of the mourning. The last part, which is appointed for the Roz-i-Qatl, comprises the events of the day on which he mat his death, and is acted with great pomp before the King, in the largest square of the city. The subject, which is full of affecting incidents, would of itself excite great interest in the breasts of a Christian audience; but allied as it ii with all the religious and national feelings of the Persians. It awakens their strongest passions. Al-Husain would be a hero in our eyes; in theirs he is a martyr. The vicissitudes of his life, his dangers in, the desert, his fortitude, his invincible courage, and his devotedness at the hour of his death, are all circumstances upon which the Persians dwell with rapture, and which excite in them an enthusiasm not to be diminished by lapse of time. The celebration of this mourning keeps up in their minds the remembrance of those who destroyed him, and consequently their hatred for all Musalmans who do not partake of their feelings. They execrate Yazid and curse ‘Umar with such rancour, that it is necessary to have witnessed the scenes that are exhibited in their cities to judge of the degree of fanaticism which possesses them at this time. I have seen some of the most violent of them as they vociferated, O Husain! “walk about the streets almost naked, with only their loins covered, and their bodies streaming with blood by the voluntary cuts which they have given to themselves, either as acts of love, anguish, or mortification. Such must have been the cuttings of which we read in Holy Writ, which were forbidden to the Israelites by Moses (Lev. xix. 28, Deut. xiv. 1), and, these extravagances, I conjecture, must resemble the practices of the priests of Basl, who cried aloud and cut themselves after this manner with knives and lancets, till the blood gushed out upon them. 1 Kings xviii. 28; see also Jeremiah xvi. 5,6, and 7.

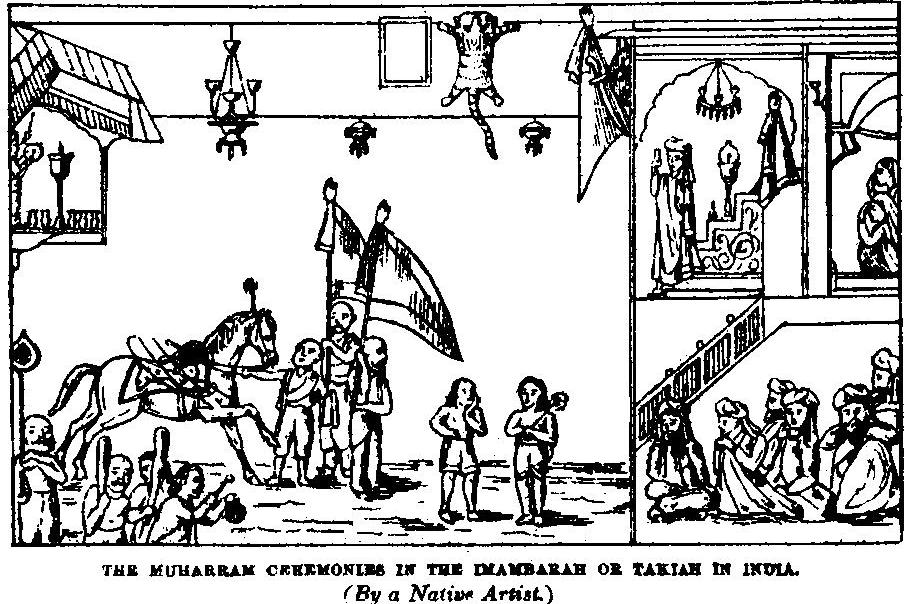

The preparations which were made throughout the city consisted in erecting large tents, that are there called takiyah., in the streets and open places, in fitting them up with, black linen and furnishing them with objects emblematical of the mourning. These tents are erected either at the joint expense of the district, or by men of consequence, as an act of devotion; and all ranks of people have a free access to them. The expense of a takiyah consists in the hire of a mulla, or priest, of actors and their clothes, and in the purchase of lights. Many there are who seize this opportunity of atoning for past sins, or of rendering thanks to heaven for some blessing, by adding charity to the good act of erecting a takiyah, and distribute gratuitous food to those who attend it.

Our neighbour Muhammad Khan had a tazkiyah in his house, to which all the people of the district flocked in great numbers. During the time of this assemblage we heard a constant noise of drum., cymbals, and trumpets. We remarked that besides the takiyah in different open places and streets of the town, a wooden pulpit, without any appendage, was erected, upon which a mulla, or priest, was mounted, preaching to the people who were collected around him. A European ambassador, who is said to have intrigued with Yazid in favour of al-Husain, was brought forward to be an actor in one of the parts of the tragedy, and the populace were in consequence inclined to look favourably upon us. Notwithstanding the excitation of the public mind, we did not cease to take our usual rides, and we generally passed unmolested through the middle of congregations, during the time of their devotions. Such little scruples have they at our seeing their religious ceremonies, that on the eighth night of the Muharram the Grand Vizier invited the whole of the embassy to attend his takiyah. On entering the room we found a large assembly of Persians clad in dark coloured clothes, which, accompanied with their black caps, their black beards, and their dismal faces, really looked as if they were afflicting their souls. They neither wore their daggers, nor any parts of their dress which they look upon as ornamental A mulla of high consideration sat next to the Grand Vizier, and kept him in serious conversation, whilst the remaining part of the society communicated with each other in whispers. After we had sat some time, the windows of the room in which we were seated were thrown open, and we then discovered a priest placed on a high chair, under the covering of a tent, surrounded by a crowd of the populace; the whole of the scene being lighted up with candles. He commenced by an exordium, in which he reminded them of the great value of each tear shed for the sake of the Imani al-Husain, which would be an atonement for a past life of wickedness; and also informed them with much solemnity, that whatsoever soul it be that shall not be afflicted in the same day, shall be cut off from among the people. He then began to read from a book, with a sort of nasal chant, that part of the tragic history of al-Husain appointed for the day, which soon produced its affect upon his audience, for he scarcely had turned over three leaves, before the Grand Vizier commenced to shake his head to and fro, to utter in a most piteous voice the usual Persian exclamation of grief. “Wahi! Wahi! Wahi!” both of which acts were followed in a more or less violent manner by the rest of the audience. The chanting of the mulla lasted nearly an hour, and some parts of his story were indeed pathetic, and well calculated to rouse the feelings of a superstitions and lively people. In one part of it, all the company stood up, and I observed that the Grand Vizier turned himself towards the wall, with his hand extended before him, and prayed. After the mulla had finished, a company of actors appeared, some dressed as women, who chanted forth their parts from slips of paper, in a sort of recitative, that was not unpleasing even to our ears. In the very tragical parts, most of them appeared to cry very unaffectedly; and as I sat near the Grand Vizier, and to his neighbour the priest. I was witness to many real tears that fell from them. In some of these mournful assemblies, it is the custom for a mulla to

go about to each person at the height of his grief, with a piece of cotton in his hand, with which he carefully collects the falling tears, and which he then squeezes into a bottle, preserving them with the greatest caution. This practically illustrates that passage in the 56th Psalm, verse 8, “Put thou my tears into thy bottle, some Persians believe that in the agony of deaths when all medicines have failed, a drop of tears so collected, put into the mouth of a dying man, has been known to revive him; and it is for such use, that, they are collected.

On the Roz-i-Qatl, or day Of martyrdom, the tenth day. the Ambassador was invited by the King to be present at the termination of the ceremonies, in, which the death of al-Husain was to be represented. We set off after breakfast, and placed ourselves in a small tent, that was pitched for our accommodation over an arched gateway, which was situated close to the room in which His Majisty was to be seated.

We looked upon the great square which is in front of the palace, at the entrance of which we perceived a circle of Cajars, or people of the King’s own tribe, who were standing barefooted, and beating their breasts in cadence to the chanting of one who stood in the centre, and with whom they now and then joined their voices in chorus. Smiting the breast is a universal act throughout the mourning; and the breast is made bare for that purpose, by unbuttoning the top of the shirt. The King, in order to show his humility, ordered the Cajars, among whom were many of his own ‘relations, to walk about without either shoes or stockings, to super-intend the order of the different ceremonies about to be performed, and they were to be seen stepping tenderly over the stones, with sticks in their hands, doing the duties of menials, now keeping back a crowds then dealing out blows with their sticks, and settling the order of the processions.

Part of the square was partitioned was partitioned off by an enclosure, which was to represent the town of Karbala’, near which al-Husain was put to death; and close to this were two small tents, which were to represent his encampment in the desert with his family. A wooden platform covered with carpets, upon which the actors were to perform, completed all the scenery used on the occasion.

A short time after we had reached our tent, the King appeared, and although we could not see him, yet we were soon apprised of his presence by all the people standing up, and by the bowing of his officers. The procession then commenced as follows ;—First came a stout man, naked from the waist upwards, balancing in his girdle a long thick pole, surmounted by an ornament made of tin, curiously wrought with devices from Qur’an, in height altogether about thirty feet. Then another, naked like the former, balanced an ornamental pole in his girdle still more ponderous, though not so high, upon which a young darwesh resting his feet upon the bearer’s girdle had placed himself, chanting verses with all his might in praise of the King. After him a person of more strength and more nakedness, a water carrier, walked forwards, bearing an immense leather sack filled with water slung over his back. This personage, we were told, was emblematical of the great thirst which al-Husain suffered in the desert.

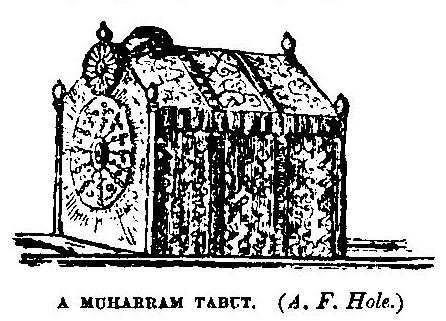

A litter in the shape of a sarcophagus, which was called Qabr-i-Husain, or the tomb of al-Husain (a Ta’ziyah) succeeded, borne on the shoulders of eight men. On its front was a large oval ornament entirely covered with precious stones, and just above it, a great diamond star. On a small projection were two tapers placed on candlesticks enriched with jewels. The top and sides were covered with Cashmere shawls, and on

the summit rested a turban, intended to present the head-dress of the Khalifah. On each side walked two men bearing poles from which a variety of beautiful shawls were suspended.. At the top of which were representations of al-Husain a hand studded with jewelry.

After this came four led horses, caparisoned in the richest manner. The fronts of their beads were ornamented with plates, entirely covered with diamonds, that emitted a thousand beautiful rays. Their bodies were dressed with shawls and gold stuffs; and on their saddles were placed some objects emblematical of the death of al-Husain. When these had passed, they arranged themselves in a row to the right of the King’s apartment. thrown over their naked bodies, marched forwards. They were all begrimed with blood; and each brandishing a sword, they sang a sort of a hymn, the tones of which were very wild. These represented the sixty-two relations, or the Martyrs, as the Persians call them, who accompanied al-Husain, and were slain in defending him. Close after them was led a white horse, covered with artificial wounds, with arrows stuck all about him, and caparisoned in black, representing the horse upon which al-Husain was mounted when he was killed. A band of about fifty men, striking two pieces of wood together in their hands, completed the procession. They arranged themselves in rows before the King, and marshalled by a maître de ballet, who stood in the middle to regulate their movements, they performed a dance clapping their hands in the best possible time. The maître de ballet all this time sang in recitative, to which the dancers joined at different intervals with loud shouts and reiterated clapping of their pieces of wood.

The two processions were succeeded by the tragedians. Al-Husain came forward, followed by his wives, sisters, and first relatives. They performed many long and

tedious acts; but as our distance from the stage was too great to hear the many affecting things which they, no doubt said to each other, we will proceed at once to where the unfortunate al-Husain lay extended on the ground, ready to receive the death-stroke from a villain dressed in armour, who acted the part of executioner. At this moment a burst of lamentation issued from the multitude, and heavy sobs and real tears came from almost every one of those who were near enough to come under our inspection. The indignation of the populace wanted some object upon which to vent itself, and it fell upon there of the actors who had performed the part of Yazid’s soldiers. No sooner was al-Husain killed, than they were driven off the ground by a volley of stones, followed by shouts of abuse. We were informed that it is so difficult to procure performers to fill these characters, that on the present occasion a party of Russian prisoners were pressed into the army of Yazid, and they made as speedy an exit after the catastrophe as it was in their power.

The scene terminated by the burning of Karbala. Several reed huts and been constructed behind the enclosure before mentioned, which of a sudden were set on fire. The tomb of al-Husain was seen covered with black cloth, and upon it sat a figure disguised in a tiger’s skin, which was intended to represent the miraculous lion, recorded to have kept watch over his remains after he had been buried. The most extraordinary part of the whole exhibition was the representation of the dead bodies of the martyrs; who having been decapitated, were all placed in a row, each body with a head close to it. To effect this, several Persians buried themselves alive, leaving the head out just above ground whilst, others put their heads under ground, leaving out the body. The heads and bodies were placed in such relative positions to each other as to make it appear that they had been severed. This is done by way of penance; but in hot weather, the violence of the execution has been known to produce death. The whole ceremony was terminated by a khutbah, or oration, in praise of al-Husain. (Morier’s Second Journey through Persia.)

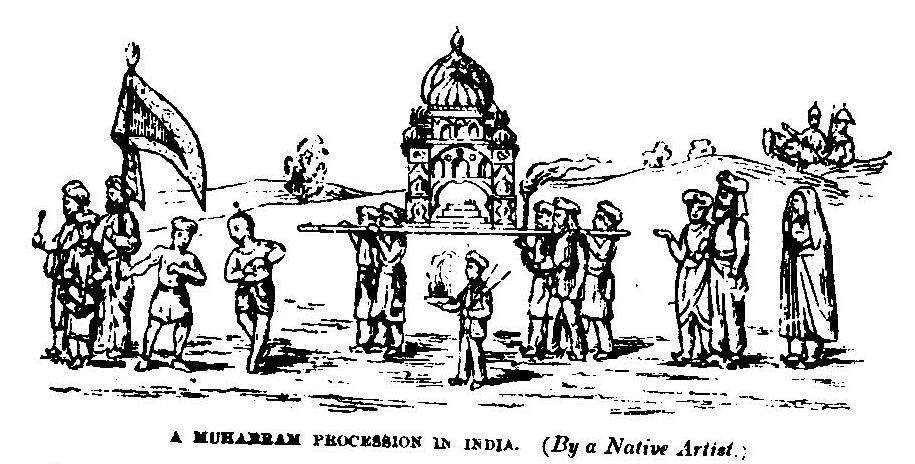

The martyrdom of Hasan and Husain is celebrated by the Shiahs all over India, during the first ten days of the month of Mohurrum Attached to every Shiah’s house is an Imambarrah, a hall or inclosure built expressly for the celebration of the anniversary of the death of Husain. The enclosure is generally arcaded along its side, and in most instances it is covered in with a domed roof. Against the side of the Imambarrah, directed toward, Mecca, is set the tabut — also called tazia (ta’ziyah), or model of the tombs at Kerbela. In the houses of the wealthier Shiahs, these tabuts are fixtures and are beautifully fashioned of silver and gold, or of ivory and ebony, embellished all over with inlaid work. The poorer Shiahs provide themselves with a tabut made for the occasion of lath and plaster, tricked out in mica and tinsel. A week before the new moon of the Mohurrum, they enclose a space called the tabut khana in which the tabut is prepared: and the very moment the new moon is seen, a spade is struck into the ground before “the enclosure of the tombs,” when a pit afterwards dug, in which a bonfire is lighted, and kept burning through all the ten days of the Mohurrum solemnities. Those who cannot afford to erect a tabut khana, or even to put up a little tabut or taziah in their dwelling-house, always have a Mohurrum fire lighted, if it consist only of a night-light floating at the bottom of an earthen pot or basin sunk in the ground. It is doubtful whether this custom refers to the trench of fire Husain set blazing behind his camp, or is a survival from the older Ashura (ten days) festival, which is said to have been instituted in commemoration of the deliverance of Hebrew Arabs from Pharaoh and his host at the Red Sea; or from the yet more ancient Bael fire. All day long the passers by stop before the

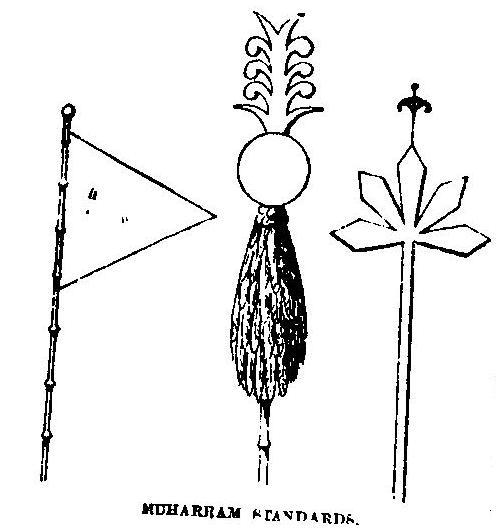

fires and make their vows over them, and all night long the crowds dance round them, and leap through the flames and scatter about the burning brands snatched from them. The tabut is lighted up like an altar, with innumerable green wax candles, and nothing can be more brilliant than the appearance of an Imambarrah of white stone, or polished white stucco, picked out in green, lighted up with glass chandeliers, sconces, and oil-lamps, arranged along the leading architectural lines of the building, with its tabut on one side, dazzling to blindness. Before the tabut are placed the “properties ” to be used by the celebrants in the “Passion Play,” the bows and arrows, the sword and spear, and the banners of Husain, &c.; and in front of it is set a movable pulpit, also made of the richest materials, and covered with rich brocade in green and gold. Such is the theatre in which twice daily during the first ten day’s of the month of Mohurram, the deaths of the first martyrs of Islam are yearly commemorated in India. Each day has its special solemnity, corresponding with the succession of events during the ten days that Husain was encamped on the fetal plain of Kerbela: but the prescribed order of the services in the daily development of the greet Shiah function of the Mohurrum would appear not to be always strictly observed in Bombay (Polly’s Miracle Play of Hasan and Husain, Preface, p. xvii.)

The drama, or “Miracle Play” which is recited in Persian during Moharram has been rendered into English by Colonel Sir Lewis Pelly, K..B. (Alln & Co.. 1879). from which we take the death scene of al-Hsain in the battle-field of Karbala, a scene which, the historian Gibbon (Decline and Fall, vol. ix. ch. 341) says, “in a distant age and climate, will awaken the sympathy of the coldest reader.”

“Husain. — I am sore distressed at the unkind treatment received at the hands of the cruel heavens. Pitiful tyranny is exercised towards me by a cruel, unbelieving army! All the sorrows and troubles of this world have overwhelmed me! I am become a butt for the arrow of affliction and trouble. I am a holy bird stript of its quills and feathers by the hand of the archer of tyranny, and am become, O friends, utterly disabled, and unable to fly to my sacred next. They are going to kill are mercilessly, for no other crime or guilt except that I happen to be a prophet’s grandson.

“Shimar (challenging him). — O Husain, why dost thou not appeal in the field? Why dost not thy majesty show thy face in battle? How long art thou going to sit still without displaying thy valour in war? Why dost thou not put on thy robe of martyrdom and come forth? If thou art indeed so magnanimous as not to fear death, if thou caveat not about the whistling sounds of the arrows when let fly from the bow, mount thou, quickly, thy swift horse named Zu’l janab, and deliver thy soul from so many troubles. Yea, come to the field of battle, be it as it may. Enter soon among thy women, and with tears bid them a last farewell; then come forth to war, and show us thy great fortitude.

“Husain (talking to himself). — Although the accursed fellow, Shimar, will put me to death in an hour’s time, yet the reproachful language of the enemy seems to be worse than destruction itself. It is better that the foe should sever my head cruelly, from the body, than make me hear these abusive words. What can I do? I have no one left to help me, no Kasim to hold my stirrup for a minute when about to mount. All are gone! Look around if thou canst find anyone to defend the descendant of Muhammad, the chosen of God—if thou canst see any ready to assist the holy family of God’s Prophet! In this land of trials there is no kind protector to have compassion on the household of the Apostle of God, and befriend them.

“Zainab. — May I be offered for the sad tones of thy voice, dear brother! Time has thrown on my head the black earth of sorrow. It has grieved me to the quick. Wait, brother, do not go till thy Kasim arrives. Have patience for a minute, my ‘Ali Akbar is coming.

“Husain (looking around). — Is there one who wishes to please God, his Maker? Is there any willing to behave faithfully towards his real friends? Is there a person ready to give up his life for our sake, to save us, to defend us in this dreadful struggle of Karbala?

“Zainab. —O Lord, Zainab’s brother has no one to assist or support him! Occasions of his sorrows are innumerable, without anyone to sympathize with him in the least? Sad and desolate, he is leaning on his spear! He has bent his neck in a calamitous manner; he has no famous ‘Ali Akbar, no renowned ‘Abbas any more!

“Husain. — Is there anyone to pity our condition, to help us in this terrible conflict of Karbala? Is there a kind soul to give us a hand of assistance for God’s sake?

“Zainah. — Brave cavalier of Karbala, it is not fitting for thee to be so hurried. Go a little more slowly; troubles will come quickly enough. Didst thou ever say thou hadst a Zainab in the tent? Is not this poor creature weeping and mourning for thee?

“The Imam Husain— Dear sister, thou rest of my disquieted, broken heart, smite on thy head and mourn, thou thousand noted nightingale. Today I shall be killed by ignoble Shimar. Today shall the rose turned out of its delightful spot by the tyranny of the thistle. Dear sister, if any dust happen to settle on the rose cheeks of my lovely daughter Sukainah, he pleased to wash away most tenderly with the rose-water thy tears? My daughter has been accustomed to sit always in the dear lap of her father whenever she wished to rest; for my sake, receive and caress her in thy bosom.

“Zainab. — O thou intimate friend of this assembly of poor afflicted strangers, the flaming effect of thy speech has left no rest to my mind. Tell me, what have we done that thou shouldest so reward us? Who is the criminal among us for whose sake we must suffer thus? Take us back, brother, to Madinah, to the sacred monument of our noble grandfather; let us go home, and live like queens in our own country.

“Husain. — O my afflicted, distressed, tormented sister, would to God there were a way of escape for me! Notwithstanding they have cruelly cut down the cypress-like stature of my dear son ‘Ali Akbar; notwithstanding Kasim my lovely nephew tinged himself with his own blood; still they are intent to kill me also. They do not allow me to go back from Irak, nor do they let me turn elsewhere. They will neither permit me to go to India nor the capital of China. I cannot set out for the territory of Abyssinia, or take refuge in Zanzibar.

“Zainab. — Oh, how am I vested in my mind dear brother, on hearing these sad things! May I die, rather than listen to such affecting words any more! What shall we, an assembly of desolate widows and orphans, do after thou art gone? Oh! how can we live?

“Husain. — O miserable creature, weep not now, nor be so very much upset; thou shalt cry plentifully hereafter, owing to the wicked ness of time. When the wicked Shimar shall sever my head from the body; when thou shalt be made a captive prisoner, and forced to ride on an unsaddled camel; when my body shall be trampled under foot by the enemy’s horses, and trodden under their hoofs; when my beloved Sukainah shall be so cruelly struck by Shimar, my wicked murderer; when they shall lead thee away captive front Karbala to Shsm and when they shall make thee and others live there in a horrible, ruined place; yes., when thou shalt see all this then thou mayest, and verily wilt, cry. But I admonish thee, sister, since this sad case has no remedy but patience, to resign the whole matter, submissively, to the Lord, the good Maker of all! Mourn not for my misfortune, but bear it patiently, without giving occasion to the enemy to rejoice triumphantly on this account, or speak reproachfully concerning us.

“Kulsum. — thou struttest about gaily, O Husain, thou beloved of my heart. Look a little behind thee; see how Kulsum is sighing after thee with tearful eyes! I am strewing pearls in thy way, precious jewels from the sea of my eyes! Let me put my head on the hoof of thy winged steed, Zu’l janab.

Husain. — Beloved sister, kindle not a fire to my heart by so doing take away thy head from under the hoof of my steed. O thousand-noted nightingale, sing not such a sad-toned toned melody. I am going away; be thou thou kind keeper of my helpless ones.

“Kulsum.- Behold what the heavens have at length brought on me! What they have done also to my brother! Him they have made to have parched lips through thirst, and me they have caused to melt into water, and gush out like tears from the eyes! Harah severity is mingled with tyrannous cruelty.

“Husain. — Trials, afflictions, the thicker they fall on man, the better, dear sister, do they prepare him, for his journey heavenward. We rejoice in tribulations, seeing they are but temporary, and yet they work out an eternal and blissful end. Though it is predestined that I should suffer martyrdom in is predestined that I should suffer martyrdom in this shameful manner, yet. the treasury of everlasting happiness shall be at my disposal as a consequent reward. Thou must think of that, and be no longer sorry. The dust raised in the field of such battles is as highly esteemed by me, O sister, as the philosopher’s stone was, in former times, by the alchemists; and the soil of Karbala is the sure remedy of my inward pains.

“Kulsum. May I be sacrificed for thee? Since this occurrence is thus inevitable; I pray thee describe to thy poor sister Kulsum her duty after thy death. Tell me, where shall I go, or in what direction set my face? What am I to do? And which of thy orphan children am I to caress most?

Husain. Show thy utmost kindness, good sister, to Sukainah, my darling girl, for the pain of being fatherless, is most severely felt by children too much fondled by their parents, especially girls. I have regard to all my children, to be sure, out I love Sukainah most.

“An old Female Slave of Husain’s mother. — Dignified master, I am sick and weary in heart at the bare idea of separation from thee. Have a kind regard to me, an old slave, much stricken with age. Master, by thy soul do 1 swear that I am altogether weary of life. I have grown old in thy service; pardon me, please, all the faults ever committed by me.

“Husain.—Yes. thou hast served us, indeed, for a very long time. Thou hast shown much affection and love toward me and my children. O handmaid of my dear mother Fatimah; thou hast verily suffered. much in out house how often didst thou grind corn with thine own hand for my mother! Thou bast also dandled Husain most caressingly in thy arms. Thou art black-faced, that is true, but thou hast, I opine, a pure white heart, and ant much esteemed by us. To-day I am about to leave thee, owing thee, at the same time, innumerable thanks for the good services thou hast performed; but I beg thy pardon for all inconsiderate actions on my part.

“The Maid. — May I be a sacrifice for thee, thou royal ruler of the capital of faith! turn not my days black, like my face, thou benevolent master. Truly I have had many troubles on thy behalf. How many nights have I spent in watchfulness at thy cradle! At one moment I would caress thee in my arms, at another I would fondle thee in my bosom. I became prematurely old by my diligent service, O Husain! Is it proper now that thou shouldst put round my poor neck the heavy chain of thy intolerable absence? Is this, dear master. the reward of the services I have done thee?

“Husain. —Though thy body, O maid, is now broken down by age and infirmity, yet thou hast served us all the days of thy life with sincerity and love; thou must knew, therefore, that thy diligence and vigilance will never be disregarded by us. Excuse me today, when I am offering my body and soul in the cause of God, and cannot help thee at all; but be sure I will fully pay the reward of thy services in the day of universal account.

“The Maid. .-Dost thou remember, good sir, how many troubles I have suffered with thee for the dear sake of ‘Ali Akbar, the light of thine eyes? Though I have not suckled him with my own breasts, to be sure, yet I laboured hard for him till he reached the age of eighteen years and came here to Karbala. But, alas! dear flourishing Ali Akbar has been this day cruelly killed—what a pity! and I strove so much for his sake, yet all, as it were, in vain. Yes, what a sad loss!

“Husain. – Speak not of my ‘Ali Akbar any more, O maiden, nor set fire to the granary of my patience and make it flame. (Turning to his sister.) Poor distressed Zainab, have the goodness to be kind always to my mother’s old maid, for she has experienced many troubles in our family; she has laboured hard in training ‘Ali Akbar my son.

“Umm Lailah (the mother of ‘Ali Akbar). — The elegant stature of my Akbar fell on the ground like, as a beautiful cypress tree it was forcibly felled! Alas for the memory of thy upright stature! Alas, O my youthful of handsome form and appearance! Alas my troubles at night-time for thee! How often did I watch thy bed, singing lullabies for thee until the morning! How sweet is the memory of those times! yea, how pleasant the very thought of these days! Alas, where art thou now, dear child? O thou who art ever remembered by me, come and see thy mother a wretched condition, come!

“Husein. — O Lord, why is this mournful voice so affecting? Methinks the owner of it, the bemoaning person, has a flame in her heart. It resembles the doleful tone of a lapwing whose wings are burned! like as when a miraculous lapwing, the companion of Solomon the wise, the king of God’s holy people received intelligence suddenly about the death of its royal guardian!

“Umm Lailah. — Again I am put in mind of try dear son of my heart, melted into blood, poar thyself forth! Dear son, whilst thou wast alive, I had some honour and respect, everybody had some regard for me; but since thou art gone, I am altogether abandoned. Woe be to me! woe be to me! I am despised and rejected. Woe unto me! woe unto me!

“Husain. — Do not set fire to the harvest of my soul any further. Husain is, before God, greatly ashamed of his shortcomings towards thee. Come out from the tent, for it is the last meeting previous to separating from one another for ever; thy distress is an additional weight to the heavy burden of my grief.

“The Mother of ‘Ali Akbar. — I humbly state it, O glory of all ages, that I did not expect from thy saintship that thou wouldest disregard thy handmaid in such a way. Thou dost show thy kind regard and favour to all except me. Dost thou not remember my sincere services done to thee? Am I not by birth a descendant of the glorious kings of Persia, brought as a captive to Arabia when the former empire fell and gave place to the new-born monarchy of the latter kingdom? The Judge, the living Creator, was pleased to grant me an offspring, whom, we called ‘Ali Akbar, this day lost to us for ever. May I be offered for thee! While ‘Ali Akbar my son was alive, I had indeed a sort of esteem and credit with the; but view that my cypress, my newly sprung up cedar, is am justly felled, I have fallen from credit too, and must therefore shed tears.

“Husain. — Be it known unto thee, O thou violet of the flower-garden of modesty, that thou art altogether mistaken. I swear by the holy enlightened dust of my mother Zahrah’s grate, that thou art more honourable and dearer now than ever. 1 well remember the affectionate recommendations of ‘Ali Akbar our son, concerning thee. How much he was mindful of thee at the moment of his speaking! How tenderly he cared for thee, and spoke concerning thee to every one of his family.

“‘Ali Akbar’s Mother. O gracious Lord! I adjure thee, by the merit of my son ‘Ali Akbar, never to lessen the shadow of Husain from over my head. May no one ever be in my miserable condition —never be a desolate, homeless woman, like me!

“Husain. — O thou unfortunate Zainab, my sister, the hour of separation is come! The day of joy is gone for ever! The night of affliction has draw near! Drooping, withering sister, yet most blest in thy temper, I fear to make known.

“Zainab. – May I be a sacrifice for thy heart, thou moon-faced, glorious sun! there is nobody here, if thou hast a private matter to disclose so thy sister.

“Husain. — Dear unfortunate sister, who art already severely vexed in heart, if I tell thee what my request is, what will be thy condition then ? Though I cannot restrain myself from speaking, still I am in doubt as to which is better, to speak, or to forbear.

“Zainab. — My breast is pierced! My heart boils within me like a cauldron, owing to this thy conversation. Thou son! of thy sister, hold not back from Zainab what thou hast in thy mind.

“Husein. —— My poor sister, I am covered with shame before thee, I cannot lift up my head. Though the request is a trifle, yet I know it is grievous to thee to grant. It is this: bring me an old, dirty, ragged garment to put on. But do not ask me, I pray thee, the reason why, until I myself think it proper to tell thee.

“Zainab. —I am now going to the tent to fetch thee what thou seekest; but I am utterly astonished, brother, as to why thou dost want this loathsome thing. (Returning in a tattered shirt.) Take it, here, is the ragged robe for which thou didst ask. I wonder what thou wilt do with it.

“Husain.—Do not remain here, dear sister. Go for awhile to thine own tent; for if thou see that which I am about to do, thou wilt he grievously disturbed. Turn to thy tent, poor miserable sister, listen to what I say, and leave me, I pray thee, alone.

“Zainab (going away). — I am gone, but I am sorry I cannot tell what this enigma means. It is puzzling indeed! Remain thou with thy mysterious cost. O Husain! May all of us be offered as a ransom for thee, dear brother. Thou art without any to assist or befriend thee! Thou art surrounded by the wicked enemy! Yes, thy kind helpers have all been killed by the unbelieving nation!

“Husain. (putting on the garment). — The term of life has no perpetual duration in itself. Who ever saw in a lower garden a rose without its thorn! I will put on his old robe close to my skin, and place over it my new apparel, though neither the old nor the of this world can be depended on. I hope Zainab has not been observing what I have been doing, for poor creature, she can scarcely bear the sight of any such like thing.

“Zainab. — Alas! I do not know what is the matter with Husain my brother. What has an old garment to do with being a king? Dost thou desire, O Husain, that the enemy should come to know this thing and reproach thy sister about it? Put off, I pray thee, this old ragged garment, otherwise I shall pull off my head-dress, and uncover my head for shame.

“Husain. — Rend not thy dress, modest sister, nor pull off thy head-covering. ‘There is a mystery involved in my action. Know that what Husain has done has a good meaning in it. His putting on an old garment is without its signification.

“Zainab. — What mystery can be in this work, thou perfect high priest of faith? I will never admit any until thou shalt have fully explained the thing according to my capacity.

“The Imam. — Today, dear sister, Shimar will behave cruely towards me. He will sever my dear head from the body. His dagger not cutting my throat, he will be obliged to sever my head from behind. After he has killed me, when he begins to strip me of my clothes, he may perchance be ashamed to take off this ragged robe and thereby leave my body naked on the ground.

“Zanaib. — O Lord, have mercy on my distracted heart! Thou alone art aware of the state of my mind. Gracious Creator, preserve the soul of Hussain! Let not heaven pull down my house over me!

“Sakainah. — Dear father, by our Lord it is a painful thing to be fatherless; a misery, a great calamity to be helpless, bleeding in the heart, and an outcast! Dismount from the saddle, and make me sit by thy side. To pass over me or neglect me at such a time is very distressing. Let me put my head on thy deer lap. O father. It is sad thou shouldst not be aware of thy dear child’s condition.

“Husain. — Bend not shy neck on one side, thou my beloved child, nor weep so sadly, like an orphan. Neither moan so melodiously, like a. disconsolate nightingale. Come, lay thy dear head on my knees once more, and shod not so copiously a flood of tears from thine eyes, thou spirit of my life.

“Sukainah. – Dear father, thou whose lot is but grief, have mercy on me, mercy! O thou my physician in every pain and trouble, have pity on me! have pity on me! Alas, my heart, for the mention of the word separation! Alas, my grievance, for what is unbearable!

“Husain. – Groan not, wail not, my dear Sukainah, my poor oppressed, distressed girl. Go to thy tent and sleep soundly in thy bed until thy father gets thee some water to drink.

“Zainab. — Alas! Alas! woe to me! my Husain is gone from me! Alas! Alas! The arrow of my heart is shot away from the hand! Woe unto me, a thousand woes! I am to remain without Husain! The woshipper of truth is gone to meet his fate with a blood-stained shroud!

“Husain. — My disconsolate Zainab, be not impatient. My homeless sister, show not thyself so fretful. Have patience, sister, the reward of the patient believers is the best of all. Render God thanks, the crown of intercession is fitted for our head only.

“Zainab. — O my afflicted mother, thou best of all women, pass a minute by those in Karbala see thy daughters prisoners of sorrow! behold them amidst strangers and foreigners. Come out awhile from thy pavilion in Paradise, O Fatimah, and weep affectionately over the state of us, thy children.

“Husain. — I have become friendless and without any helper, in a most strange manner. I have lost my troop and army in a wonderful way. Where is Akbar my son? let him come to me and hold the bridle of my horse, that I may mount. Where is Kasim my nephew? will he not help me and get ready m stirrup to make me cheerful? Why should I not shed much blood from mine eyes, seeing I cannot behold ‘Abbas my standard-bearer? A brother is for the day of misfortune and calamity! A brother is better than a hundred diadems and thrones! A brother is the essence of life in the world! Its who has a brother, though he be old, yet is young. Who is there to bring my horse for me? there is none. There is none even to weep for me in this state of misery!

“Kulsum. — Because there is no ‘Ali Akbar, dear brother, to help thee, Zainab, thy sister will hold the horse for thee; and seeing ‘Abbas, thy brother, is no longer to be found, I myself will bear the standard before winged steed instead of him.

“Zainab. —— Let Zainab mourn bitterly for her brother’s desolation. Who ever saw a woman, a gentlewoman, doing the duty of a groom or servant? Who can know, O Lord, besides Thee, the sad state of Husain in Karbala, where his people so deserted him that a woman like myself is obliged to act as a servant for him.

” Kulsim. — I am a standard-bearer for Husain, the martyr of Karbala, O Lord God, I am the sister of ‘Abbas; yea, the miserable sister of both. O friends, it being the tenth day of Muharram, I am therefore assisting Husain. I am bearing the ensign for him instead of ‘Abbas my brother, his standard-bearer.

“Zainab. — Uncover your breasts a minute. O ye tear-shedding people, for it is time to beat the drum, seeing the king is going ride. O Solomon the Prophet, where is thy glory? what has become of thy pompous retinue? Where are thy brothers, nephews and companions?

“Husain. – There are none left to help me. My sister Zainab holds the bridle of the horse and walks before me. Who ever saw a lady acting thus?

“Zainab. — Thou art going all alone the souls of all be a ransom for thee! May thy departure make souls quit bodies! A resurrection will be produced in thy tent by the cry of orphans and widows.

“Husain —Sister or, though it grieves me to go, yet I do it ; peradventure I may see the face of Ashgar and the countenance of Akbar, those cypresses, those roses of Paradise.

“Zainab — Would to God Zainab had died I this very minute before thy face, in thy sight, that she might not behold such elegant bodies, such beautiful forms, rolling in their own blood

“Husain. — O poor sister, if thou die here in this land in that sudden, way that thou desirest, then who all will ride it thy stead, in the city of Kufah, on the camel’s back?

“Zainab. — Slight not my pain, dear brother, for Zainab is somewhat alarmed as to the import of thy speech. What shall I do with thy family—with the poor widows and young children?

“Husain. – O afflicted one, it is decreed I should be killed by means of daggers and swords; henceforth, dear sister, thou shalt not see me. Behold, this is separation between me and thee.

“The nephew of Husain. — Dear uncle, thou hast resolved to journey. Thou art going once again to make me an orphan. To whom else wilt thou entrust us? Who is expected to take care of us? Thou wast, dear uncle instead of my father Hasan, a defence to this helpless exiled creature.

“Husain. — Sorrow not, thou faithful child, thou shalt be killed too in this plain of trials. Return thou now to thy tent in peace, without grieving my soul any further, poor orphan!

“The Darwish from Kabul. — O Lord God, wherefore is the outward appearance of a man of God usually without decoration or ornament? And why is the lap if the man of this world generally full of gold and jewels? On what account is the pillow of this great. person the black dust of the road? and for what reason are the bed and the cushion of the rebellions made of velvet and stuffed with down? Either Islam, the religion of peace and charity, has no true foundation in the world, or this young man, who is so wounded and suffers from thirst, is still an infidel.

“Husain. — Why are thine eyes pouring down tears young darwish? Hast thou also lost an Akbar in the prime of his youth? Thou art immersed, as a water-fowl, in thy tears. Has thine Abbas been slain, thirsting, on the bank of the River Euphrates, that thou cryest so piteously? But if thou art sad only on account of my misfortune, then it matters not. Let me know whence comest thou, and whither is thy face set?

“The Darwish. — It happened, young man, that last night I arrived in this valley, and made my lodging there. When one-half of the night had passed, of a sudden a great difficulty befell me, for I heard a child bemoaning and complaining of thirst, having given up altogether the idea of living any longer in this world. Sometimes it would beat its head and cry out for water; at other times it appeared to fall on the ground, fainting and motionless. I have, therefore, brought some water in this cup for that poor child, that it may drink and be refreshed a little. So I humbly beg thee, dear sir, to direct me to the place where the young child may be found and tell me what is its name.

“Husuin. — O God, let no man be ever in my pitiful condition, nor any family in this sad and deplorable state to which I am reduced. O young man, the child mentioned by thee is the peace of my troubled mind; it is my poor, miserable little girl.

“The Darwish..—May I be offered for thee, dear sir, and for thy tearful eyes! Why should thy daughter be so sadly mourning and complaining? My heart is overwhelmed with grief for the abundance of tears running down thy cheeks. Why should the daughter of one like thee, a generous soul, suffer from thirst?

“Husain. — Know, O young man, that. we are never in need of the water of this life. Thou art quite mistaken if thou host supposed us to be of this world. If I will, I can make the moon, or any other celestial orb, fall down on the earth; how much more can I get water for my children. Look at the hollow made in the ground with my spear; water would gush out of it if I were to like. I voluntary die of thirst to obtain a crown of glory from God. I die parched, and offer myself a sacrifice for the sins of my people, that they should be saved from the wrath to come.

“The Darwish. — What is thy name, sir? I perceive that thou art one of the chief saints of the most beneficent God. It is evident to me that thou art the brightness of the Lord’s image, but I cannot tell to which sacred garden thy holy rose belongs.

“Husain. — O darwish, thou wilt so be informed of the whole matter, for thou shalt be a martyr thyself; for thy planes and the result thereof have been revealed to we. Tell me, O darwish, what is the end thou hast in view in this thy hazardous enterprise? When thou shalt have told me that, I will disclose to thee who I am.

“The Darwish.. — I intend, noble sir, after have known the mystery of thy affairs, to set out, if God wills, from Karbala to Najaf. namely, to the place where ‘Ali, the highly exalted king of religion, the sovereign lord of the empire of existence, the supreme master of all the darwishes, is buried. Yea, I am going to visit the tomb of ‘Ali, the successor of the chosen of God, the son-in-law of the Prophet, the lion of the true Lord, the prince of believers, Haidar, the champion of. faith.

“Husain. — Be it known unto the O darwish, that I, who am so sad and sorrowful, am the rose of the garden of that prince. I am of the family of the believers thou hast mentioned. I am Husain, the intercessor on the Day of Resurrection, the rose of the garden of glory.

“The Darwish. — May I be offered a sacrifice for thy blessed arrival! Pardon me any fault, and give me permission to fight the battle of faith, for I am weary of life. It is better for me to be killed, and delivered at once from so many vexatious of spirit. Martyrdom is, in fact, one of the glories of my faith.

“Husain. — Go forth, O atom, which aspirest to the glory of the sun: go forth, thou hast become at last worthy to know the hidden mysteries of faith. He who is slain for the sake of Husain shall have on abundant reward from God; yea, he shall be raised to life with ‘Ali Akbar the sweet sort oh Husain.

“The Darwish. (addressing Husain’s antagonists) – you cursed people have no religion at all. You are fire-worshippers, ignorant of God and his law. How long will you act unjustly towards the offspring of the priesthood? Is the account of the Day of Resurrection all false?

“Ibn Sa’d, (The general of Yazid’s army).— O ye brave soldiers of Yazid, deprive this fellow of his fund of life. Make his friends ready to mourn for him.

“Husain – Is there anyone to help me? Is there any assistant to lend me his aid?

“Ja’far (the king of jinns, with his troops, coming to Husain’s assistance). .— O king of men and jinns, O Husain, peace be on thee! O judge of corporeal and spiritual beings, peace be on thee!

“Husain. .— On thee be peace, handsome youth! Who art thou, that salutest us at such a time? Though thine affairs are not hidden from me at all, still it is advisable to ask thy name.

Ja’far. — O lord of man and jinns. I am the least of thy servants, and my name is Ja’far, the chief ruler of all the tribes of jinns. Today, while I was sitting on the glorious throne of my majesty, easy in mind, without any sad idea of thought whatever. I suddenly heard thy voice, when thou didst sadly implore assistance: and on hearing thee I lost my patience and senses. And, behold. I have come out with troops of jinns, of various abilities and qualifications, to lend thee help if necessary.

“Husain. — In the old abbey of this perishable kingdom, none can ever, O Ja’far, attain to immortality. What can I do with the empire of the world, or its tempting glories, after my dear ones have all died and gone? It is proper that I, an old man, should live, and Akbar, a blooming youth, die in the prime of age? Return thou, Ja’far, to thy home and weep for me as much as thou canst.

Ja’far (returning).,.— Alas for Hasain’s exile and helplessness! Alas for his continual groans and sighs!

“Husain (coming back from the field, dismounts his horse, and making a heap of dust, lays his head on it). O earth of Karbala, do thou assist me, I pray! since I have no mother, he thou to me instead of one.

“Ibn Sa’d orders the army to stone Husain, — O ye men of valour, Husain the son of ‘Ali has tumbled down from the winged horse if I be not mistaken, heaven has fallen to earth! It is better for you to stone him most cruelly. Dispatch him soon, with stones, to his companions.

Husain — Ah, woe to me! my forehead is broken; blood runs down my luminous face.

“Ibn Sa’d.—Who is that brave shoulder, who, in order to show his gratitude to Yazid his sovereign lord, will stop forward and, with a blow of his soymetar, slay Hussain the son of ‘Ali?

“Shimar. — I am he whose dagger is famous for bloodshed. My mother has borne me for this work alone. I care not about the conflict of the Day of Judgment; I am a worshipper of Yazid, and have no fear of God. I can make the great throne of the Lord to shake and tremble, I alone can sever from the body the head of ‘Usman the son of ‘Ali. I am he who has no share in Islam I will strike the chest of Husain, the ark of God’s knowledge, with my boots without any fear of punishment.

“Husain. — Oh, how wounds caused by arrows and daggers do smart O God, have mercy in the Day of Judgment on my people for my sake. The time of death has arrived, but I have not my Akbar with me. Would to God my grandfather the Prophet were now here to see me!

“The Prophet (appearing). — Dear Husain, thy grandfather the Prophet of God has come to see thee. I am here to behold the mortal wounds of thy delicate body. Dear child, thou hast at length suffered martyrdom by the cruel hand of my own people! This was the reward I expected from them thanks be to God! Open thine eyes, dear son, and behold thy grandfather with dishevelled hair. If thou hast any desire in thy heart, speak out to me.

“Husain. — Dear grandfather, 1 abhor life; I would rather go and visit my dear ones in the next world. I earnestly desire to see my companions and friends — above all, my dearly beloved son ‘Ali Akbar.

“The Prophet. — Be not grieved that ‘Ali Akbar thy son was killed, since it tends to the good of my sinful people on the day of universal gathering.

“Husain.—Seeing ‘Ali Akbar’s martyrdom contributes to the happiness of thy people, seeing my own sufferings gave validity to thy office of mediation, and seeing thy rest consists in my being troubled in this way, I would offer my soul, not once or twice, but a thousand times, for the salvation of thy people!

“The Prophet. — Sorrow not, dear grand-child; thou shalt be a mediator, too, in that day. At, present thou art thirsty, but tomorrow thou shalt be the distributor of the water of Al Kausar.

“Husain. — O Lord God, besides Husain, who has happened to be thus situated? Every one when he dies has at least a mother at his head. But my mother is not here to rend her garments for me; she is not alive, that she might close my eyes when I die.

“Fatimah, his mother (appearing). — I am come to see thee, my child, my child! May I die another time, my child, my child! How shall I see thee slain, my son, my son! Rolling in thine own blood, my child, my child!

Husain. — Come, dear mother. I am anxiously waiting for thee. Come, come! I base partly to complain of thee. How is it that thou hast altogether forsaken thy son? How is it thou, camest so late to visit me?

Fatimah. May I be offered for thy wounded, defaced body! Tell me, what dost thou wish thy mother to do now for thee?

“Husain. — I am now, dear mother, at the point of death. The ark of life is going to be cast on shore, mother. It is time that my soul should leave the body. Come, mother, close my eyes with thy kind hand.

“Fatima – O Lord, how difficult for a mother to see her dear child dying! I am Zahrab who am making this sad noise, because I have to close the eyes of my son Husain, who is on the point of death. Oh, tell me if thou hast any desire long cherished in thy heart, for I am distressed in mind owing to thy sad sighs!

“Husain. — Go, mother, my soul is come to my throat; go, I had no other desire except one, with which I must rise in the Day of Resurrection, namely, to see ‘Ali Akbar’s wedding.

“Shimar. — Make thy confession, for I want to sever thy head, and cause a perpetual separation between it and the body.

“Zainab — O Shimar do not go beyond thy limit; let me bind something on my brother’s.

“Husain. — Go to thy tent, sister, I am already undone. Go away; Zahrah my mother has already closed my eyes. Show to Sukainah my daughter always the tenderness of a mother. Be very kind to my child utter me.

“Shimar (addressing Husain). — Stretch forth thy feet toward the holy Kiblah, the sacred temple of Makkah. See how my dagger waves over thee! It is time to cut thy throat.

“Husain. — O Lord, for the merit of me, the dear child of thy Prophet; O Lord, for the sad groaning of my miserable sister; O Lord, for the sake of young ‘Abbas rolling in his blood, oven that young brother of mine that was equal to my soul, I pray thee, in the Day of Judgment. forgive, O merciful Lord, the sins of my grandfather’s people, and grant me, bountifully, the key of the treasure of intercession. (Dies.)” — (Pelly’s Miracle Play, vol. ii. p. 81 seqq.)

Based on Hughes, Dictionary of Islam

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved