Collective Interview with Juan Cole about his new book at AskHistorians, Reddit.com

(Rearranged for readability.)

AMA: I am Juan Cole, author of ‘Muhammad: Prophet of Peace amid the Clash of Empires’ out today. AMA

Here is the description from the publisher: “Many observers stereotype Islam and its scripture as inherently extreme or violent-a narrative that has overshadowed the truth of its roots. In this masterfully told account, preeminent Middle East expert Juan Cole takes us back to Islam’s-and the Prophet Muhammad’s-origin story. Cole shows how Muhammad came of age as the eastern Roman Empire and the Sasanian Empire of Iran fought savagely throughout the Near East and Asia Minor. Muhammad’s profound distress at the carnage of his times led him to envision an alternative movement, one firmly grounded in peace. The religion Muhammad founded, Islam, spread widely during his lifetime, relying on soft power instead of military might, and sought armistices even when militarily attacked. Cole sheds light on this forgotten history, reminding us that in the Qur’an, the legacy of that spiritual message endures./

Muhammad: Prophet of Peace amid the Clash of Empires, out October 9

*Now* available for order at Barnes and Noble

And Nicola’s Books in Ann Arbor

And Hachette

And Amazon

Georgy_K_Zhukov Moderator

Thank you very much for joining us today for the AMA. This is just a general reminder for anyone looking to post a question here. We of course welcome any and all inquiries relevant Dr. Cole’s book and research but do ask that anyone looking to ask a question keep the basic subreddit rules in mind! Principally here we expect that questions be asked politely, in good faith, and without bigoted or otherwise offensive wording towards Muslims or any other group. Users who violate these basic guidelines can expect to receive an immediate ban.

Thanks,

The Mods

iorgfeflkd

How firmly established is the historicity of Muhammad as a person?

Juan Cole

Muhammad (d. 632) is mentioned by Christian writers … already in the 630s and 640s. A bit later we have coins with his name on them. Even revisionists such as Patricia Crone freely admitted that his existence isn’t in doubt. There is also paleographic and tentative carbon 14 dating of the Sana’a palimpsest suggesting it goes back to mid-7th century; the Qur’an mentions Muhammad several times./

Zeuvembie

Islam recognizes followers of both Judaism and Christianity, is there any indication that this was deliberate on Muhammad’s part to foster peace among the related religions?

Juan Cole

Yes. I think there is a parallel between the document called the Constitution of Medina and the Qur’an’s pluralist theology of religions. The Constitution says that the Jews in Medina and the Believers in Muhammad form one nation (umma) but that the Jews have their religion and the Believers have theirs. Verses of the Qur’an like 2:62 promise salvation to righteous Jews and Christians: “Those who believed, and the Jews, and the Christians, and the Sabians, and whoever has believed in God and the Last Day and performed good works, they shall have their reward with their Lord.” So I think Muhammad was trying to put together both a political and an ecumenical alliance in Medina against the militant Meccan pagans./

Zeuvembie

Thanks for answering my question!

lcnielsen

It is certainly an interesting take on the Prophet. One more question: Your description of Muhammad makes me think of the nowadays most accepted explanation of the origins of Zoroastrianism as an explicit rejection of the glorification of warfare and warlike gods (Daeva) seen in Vedic religion”Mazda-worship, the religion that puts down the sword”, et cetera.. This was in a context of chariot warfare wreaking havoc in the Bronze Age. Of course, Zoroastrianism would later become an “imperial” religion in some of the greatest empires of antiquity. Did this parallel ever occur to you?

Juan Cole:

Good parallel! But also, as I argue below on this page, there is a comparison to be made to Christian Rome in the 300s-400s under Constantine and his successors./

TripRoberto

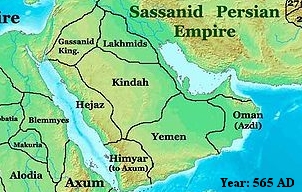

How much of the war between the Eastern Roman Empire and the Sasanian Empire would Muhammad have actually seen? Did it touch the Arabian Peninsula or did he, say, spend time living in the Levant or modern day Iraq and see it there?

Juan Cole

Oh, I think Muhammad was very much affected by the war, 603-629. Jacob of Edessa, writing in the very late 600s, says that Muhammad regularly went up to Palestine, Transjordan and Syria for trade, including in 617-19. The later Muslim biographies only speak of two trade journeys, both before he became a prophet in 610, but the Qur’an gives evidence of him being up north in the teens. Muhammad’s trade would have been disrupted by the revolt of Herakleios and Niketas in 608-610 against Emperor Phokas, and again in 613-614 when the Iranian general Shahr Varaz took Damascus and Jerusalem. The beginning of the chapter of Rome (30) explicitly takes the side of Rome and says that its victory over Iran will be God’s victory at which Muhammad’s Believers will rejoice. My book argues that the ministry of the Prophet was very much wrought up with that war, because the Meccan pagans were likely allied with Iran./

Kochevnik81

Do we have a good sense as to how Muhammad saw his community in a wider world context? I’m assuming concepts like Dar al Harb, Dar al Islam and Dar al Ahd are fleshed out in a later time … did Muhammad have a “grand strategy” beyond Mecca and the Arab tribes?

Christianity has pretty much always had the Apocalypse as a future end point, but I’m curious if Muhammad had much of a sense for what he expected Islam or the Muslim community to develop into in the future.

Juan Cole

. . . The Qur’an seems to be a partisan of the Roman Empire and it seems likely that Muhammad envisaged his Hejazi community as becoming, like Ethiopia and Armenia, part of the Byzantine commonwealth in opposition to Sasanid imperialism. There isn’t anything in the Qur’an about a realm of war and realm of peace. Rather, the Qur’an thinks peace is perfectly possible even with the militant pagans, if they will just negotiate. Later Muslim political theology asserted that Islam ought to rule, but there does not seem to me to be anything like that in the Qur’an. I think the verses used to justify that imperial attitude, like 5:29, are grossly and ahistorically misinterpreted./

Kochevnik81

Thanks, and thank you for doing this AMA!

AbouBenAdhem

In Muhammad’s time there were several large Arab groups allied to the Romans and Persians. Did Muhammad see the potential conversion of such groups as incompatible with their political loyalty to non-Arab states? Or did he envision the spread of Islam independent of political control?

Juan Cole

There isn’t any evidence in the Qur’an for thinking about the state. It supports the Roman Empire against Sasanid aggression but is otherwise silent on the question of political authority. I don’t see Muhammad as a king, but more as a prophetic mediator among the various groups (including non-Muslims) in the Hejaz.

I speculate that he may have envisioned the Muslims becoming part of the Byzantine Commonwealth, in Garth Fowden’s phrase, along with Ethiopia, Armenia and the German Arians– the polities that accepted Jesus but had vastly different theologies about him, but which were agreed in opposing Iranian expansionism.

This is my translation of the chapter of Rome 30:1-6: “Rome lies vanquished in the nearest province. But in the wake of their defeat, they will triumph after a few years. Before and after, it is God who is in command. On that day, the believers will rejoice in the victory of God; he causes to triumph whomever he will, and he is the Mighty, the Merciful. It is the promise of God; God does not break his promises, but most people do not know it.” It seems to me to say that the Roman emperor’s victory is the victory of God, that is, God works in history through temporal such states. It reminds me of Isaiah calling Cyrus the Great a messiah.

The Qur’an supports the Roman Empire in the war with Iran, I think because it sees Khosrow II, the Sasanid ruler, as the aggressor. So I just speculate that Muhammad was closer to the Jafnids and other Arab tribes who were foederati or allied cavalrymen of Rome. It is interesting that at least the later Muslim sources say that a former Jafnid court poet, Hassan al-Thabit, came to serve Muhammad in that role during the period of Iranian rule of the Levant./

Gankom

How much contact would the romans especially have had deeper in Arabia? Would most of it just been around the edges?

Also I’ve heard that a lot of Arabian men would have fought on one side of the war or the other, were they more like mercenaries, tributary fighters, vassals, allies or something different?

Juan Cole

What is becoming clear is that Arabic-speaking peoples lived under Roman rule in Palestine, Transjordan and eastern and northern Syria for 500 years after the Roman conquest of the Near East in 106 CE and before the rise of Islam. The Roman state used these Arabs in various ways. Some were townspeople as at Gerasa and Petra, and the Petra Papyri show they were bilingual in Greek. Some were limitanei or mercenaries hired for gold as border guards, as with the Thamud at Rawafa for which we have an inscription from the time of Marcus Aurelius. In the 500s, the Jafnid ruling clan led Banu Ghassan, Banu Kalb and Banu Judham as foederati or Federate cavalrymen, trained in Roman tactics and with a chain of command that went from the Arab phylarch to the dux of the garrisons as at Bostra. So Arabs were intimately entangled with the Empire in various capacities, and the empire’s authority, culture and trade clearly reached into the Hejaz or eastern Arabia. An Instagram friend of mine recently photographed an ancient building at Medina that had a Roman eagle on it!/

Gankom

Oh wow, Medina is a great deal further south then I was thinking. I knew there was extensive Roman contact, but I always imagined it much further north towards Palestine.

Just how far south into Arabia would the Roman Empire actually have extended much in the way of control, as opposed to just trade or extended influence?

Juan Cole

Roman influence in the Hejaz ebbed and flowed. Higr or Madain Saleh had a Roman garrison in the second and third centuries as I remember. The Qur’an mentions Higr but by that time Roman authority had receded up to southern Transjordan. Procopius says that the Jafnid Phylarch Jabala claimed the Hejaz and gifted it to Justinian in the mid-500s. Procopius thought the whole thing was just polite words, though. The Hejazi long distance merchants like Muhammad would have spent much of their lives under Roman rule when they were up north./

Gankom

Awesome, thanks! That’s pretty interesting.

RadiantRectangle

‘Muhammad’s profound distress at the carnage of his times led him to envision an alternative movement, one firmly grounded in peace.’

I am curious what the roots of this distress were. Does it stem from eyewitness accounts he got from travelers, merchants and the like or did he witness some himself? How affected was his home from those wars? Maybe that is a very simple question, but I am not very well read on his biography.

I am also curious if there is a change in Muhammad’s attitude regarding peace. As everybody who ever came in contact with some so called ‘Islam critics’ knows there are some passages in the Qur’an which don’t seem especially critical regarding violence. Are they in your opinion the result of a changing attitude over time? Or would you say it is always the same tone regarding war/peace and the only thing that changes is the context in which he talks?

Finally I have a question regarding your methodology. Just as in books about Jesus, Buddha or other religious figures there are obvious examples of ‘religious events’ which can’t be explained in a secular or non-religious way. Do you ignore these? Or just recount what the scripture says what happened? Or do you try to make sense of it? How it might happened ‘in real life’? How do you work with a book like the Qur’an which is both ‘divinely inspired’ according to its author and a historical document?

Also: Do you feel your attitudes regarding Muhammad as a ‘Prophet of Peace’ is something which is shared by your academic colleges or is there a divide in the professional study of early Islamic History concerning this topic?

Thanks for doing this AMA. Feel free to just answer one question if that suits you better! I know these are a lot.

Juan Cole:

I think there is evidence that Muhammad traveled for trade up to Sasanian Transjordan, Palestine and Syria during the Iranian occupation of those areas, as well as down to Sasanian Yemen, and so, yes, he would have seen some of the effects of the war himself.

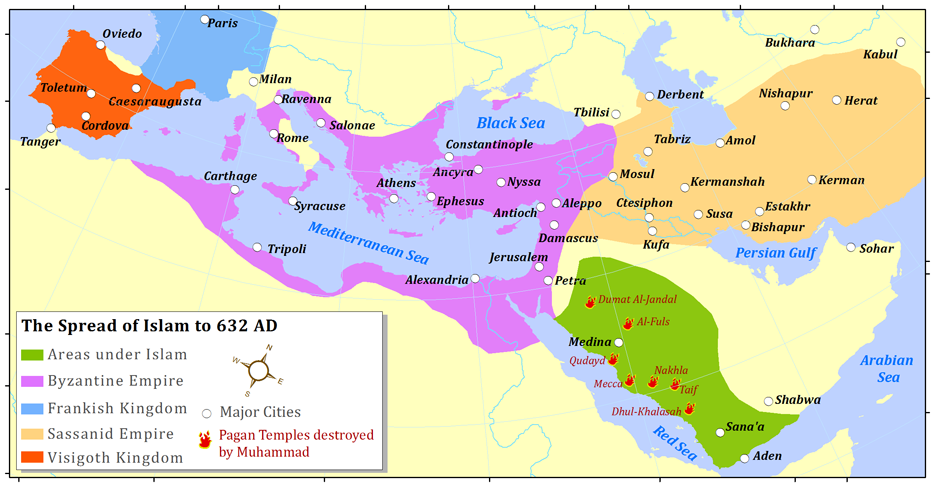

Muhammad and his believers in the Mecca period (610-622) appear to have been more or less pacifists, in accordance with the Arab custom that shrine cities like Mecca were peace sanctuaries. When they emigrated under pressure to Medina in 622, and then when the militant pagan Meccans came after them in 624, the Qur’an begins urging them to defend themselves or risk being conquered, enslaved and forcibly reconverted to paganism along with their families. The verses on war quoted by Islamophobes are all about self-defense, not aggressive warfare, and when read in context don’t sound different from church father like Augustine and Ambrose. The Qur’an consistently, however, rejects aggressive warfare and says if the attacking enemy suddenly proffers an armistice, it has to be accepted.

With regard to religious events, I take an ethnographic approach and just report what the texts say. I was trained at Northwestern in the phenomenology of religion. As a historian, I make no metaphysical judgments in this book.

Oh, I think some of my conclusions were anticipated by Fred Donner at the University of Chicago, for instance. Obviously, there are many other academics in the field who will find this book a departure. I should stress that although it is grounded in a mass of academic scholarship on the Qur’an, it presents an original take and will stir some debate./

TriceraTiger

While the major divisions within Christianity are usually theological (usually relating to some disagreement over Christology), the divisions within Islam tend to be much more openly political. Are there any historical reasons for this to be the case?

Juan Cole:

Some of the divisions in Islam are theological, too. But my book is treating the very earliest period. There were divisions, but it is hard to estimate their character. The Qur’an warns against faction-fighting, suggesting some were tribal. A faction it calls the Hypocrites seem to have been like cafeteria Catholics. They accepted the Qur’an but thought it was all right to differ with Muhammad over tactics and policy (whether to go outside Medina to make a stand and defend it, or whether to stay inside and defend from marshes and badlands, e.g.). It strikes me as all murky and remarkably little rigorous study has been done of the earliest Muslim divisions./

lcnielsen

Do you think there was a dramatic change in the attitude toward the use of military might among Muslim leaders in the early caliphates following Muhammad’s death? At what point?

Juan Cole

Yes, absolutely. I make this point explicitly in my conclusion. The Qur’an depicts Muhammad as constantly seeking mediation of conflict and only reluctantly fighting 4 small battles when attacked, but forbidding aggressive, expansionist warfare. Even later Abbasid accounts, which militarized the Prophet, admit that cities in the Hejaz– Medina, Mecca, Aden, Sana’a, Najran and Taif all threw in with Muhammad and his message rather than being conquered. They do try to turn the procession to Mecca in Jan. 630 into something military, but the Qur’an Chapter of Success (48), which I read as about the acquiescence of Mecca, disputes this, saying there was no fighting. Scholars like David Powers have questioned the story of the supposed Mu’ta campaign up to Transjordan. If we depend mainly on the Qur’an, there is no warrant for a Muslim conquest state. But one grew up in the era of the commanders of the faithful who succeeded Muhammad, anyway./

cleantoe

Objectively and honestly, what are the criticisms of your conclusion, and how would you respond to them?

Juan Cole

The book just came out today, so I don’t have any criticisms to hand yet. Just anticipating, I would guess that the Revisionists in Islamics will complain that I accept too much of the classical Muslim tradition, which isn’t written down until 130-300 years after Muhammad’s death. But if they follow the citations they’ll see that most of the book is based on the Qur’an, which I think it is now established is early seventh century. Muslim traditionalists may object that the book cites almost no hadith and disregards much of the sira or biographical literature (i.e. will have the opposite objection of the Revisionists)./

Estelindis

Among many ordinary people, Islam has the reputation of a religion of conquest, especially in its early centuries. Why would you say that is? Would you like to make any other comment on this reputation? Thank you.

Juan Cole:

Well part of it is ethnocentrism. Constantine the Great became Christian in 312, and gradually he and his successors made the Roman Empire into a Christian empire. It was a conquest state and sought to expand its territory in the Balkans, Europe, Asia Minor, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Mesopotamia, etc. This muscular Christianity was actively supported by St. Augustine. But people of Christian European heritage don’t see Christianity as a religion of conquest. The early Muslim state did go out and take over the Near East and Iran, but I argue that the commanders of the faithful and later rulers just put Islam to the same sort of purposes as Constantine and his successors had put Christianity. I don’t think Jesus would have approved of many Christian Roman policies, and I don’t think Muhammad would have approved of some of what his successors did, either./

Estelindis

Thank you.

UnrulyRulersRule

Since you’ve dug into a variety of early sources, have you found anything interesting about the Shia/Sunni divide with the Saqifah event which might not be covered by modern layman’s English sources? Perhaps some context or observations? Thanks!

Juan Cole

I mainly use the Qur’an and try to avoid the later sources, and my book ends in 632, so issues in the succession to the Prophet Muhammad really don’t come up, though I advert to them in the conclusion. We historians don’t think there were Sunnis or Shiites in the early period and hold that those traditions were constructed over centuries./

UnrulyRulersRule

Thanks for your response. I knew the question was a little off topic, so your answer is plenty satisfactory. It makes sense that those eventual divisions were not immediate, despite tracing their roots to a very early event, rather building over centuries, somewhat like the Catholic/Orthodox schism in Christianity. Thanks again.

Elm11

Hi Prof. Cole, thank you for being here!

The last two years have obviously been a tumultuous time for western governmental and societal relations with Islam and Islamic countries. From a historiographical standpoint, has the post-2016 political environment presented challenges to your field or your research?

Juan Cole:

As a professional historian, I wouldn’t want anyone to think that I wrote this book with foregone conclusions or primarily to try to intervene in our contemporary political struggles. I’ve been thinking about this work for a very long time (I studied the Qur’an academically at the American University in Cairo 1976-78). But I am glad that I came to the conclusions that I did, since I do think they will be helpful to people in thinking about Islam, or at least Islamic origins, given what else is going on in the world, and might be at least some counter to the hate literature about Islam that dominates the bestseller lists.

As for the field, it is just woefully underwritten. Only a handful of scholars of Muslim heritage have been willing to write about the Qur’an in an academic way, and the academics are therefore mostly Protestants, Catholics, Jews and atheists. Given its immense importance, amazingly little has been written about the Qur’an in English (there is more in German) from an academic point of view.

It may be that some people have been scared off by the rise of religious extremism in the Middle East. I don’t know. But in some ways I think 1970s Revisionism was more significant, since some of its proponents held that we couldn’t know anything about early 7th century Islam, since we have no contemporary sources.

I think that position was paralyzing for the field. But the studies of Qur’an manuscripts by Deroche and Sadeghi and others have, I think, given us more certitude that that text can be considered early, and primary. Even Patricia Crone turned before her untimely death to using the Qur’an as a primary source. So perhaps now more academics will turn to the subject, and I’d be delighted if I could provoke some graduate students to take it up./

henry_fords_ghost

The massacre of the Banu Quarayza stands out as an unusually violent episode in a “conquest” typified (in Islamic sources at least) by clever diplomacy. How atypical was this incident, and what caused it?

The Wikipedia article seems to suggest that the decision was based on instructions from the book of Deuteronomy – is that plausible?

Juan Cole

There isn’t anything in the Qur’an about any massacres. In fact, the Qur’an denounces Pharaoh for behaving that way. In Stories 28:4, the Qur’an says, “Now Pharaoh exalted himself in the land and divided its inhabitants into factions, abasing one party of them, slaughtering their sons, and sparing their women; for he was a worker of corruption.” The Qur’an (47:4) says POWs should be released, whether by grace or ransom, even while the war is ongoing. The story of a massacre of Jews of the Banu Qurayza is directly contradictory to what we find in the Qur’an and I view it as later Abbasid anti-Semitism./

superfahd

The story of a massacre of Jews of the Banu Qurayza is directly contradictory to what we find in the Qur’an and I view it as later Abbasid anti-Semitism.

I’d like some more details on this please. Do you mean to say that the incident didn’t happen? Or that something happened that was exaggerated by the Abbasids at a later date?

Juan Cole:

There are two short passages in the Qur’an about some sort of conflict with those who “paganized from among the People of the Book.” I think this means biblical communities who allied with pagan Mecca against Muhammad and his Believers. We cannot know whether these were Jews, Christians or some other group. In one of the passages, the opening verses of 59 The Gathering, the Believers besiege the offending village and cut down its palm trees, depriving the inhabitants of their livelihood and reason to live there. So they are allowed to depart. In the other passage, Confederates 33:26, there is a short battle and the Believers give quarter to the defeated foe. Neither passage of the Qur’an sounds anything at all like the later Abbasid accounts of Banu Qurayza and I personally think these latter are fictional tropes impelled by some 8th or 9th century conflict with Jews in Damascus or Baghdad./

paintvulgarpicture

Just from your description here you highlight Muhammed as a figure generally seeking and promoting a peaceful existence. How do you reconcile that with events such as the massacre of the Banu Qurayza, which seem to go beyond mere violence? Reading Safi’s Memories of Muhammed he suggests some scholars question the historicity of the event, is this a common/well supported view?

Juan Cole:

I don’t know if there is a consensus, but Marco Schoeller in Germany rejects the historicity of the Banu Qurayza massacre and I certainly do. I view the Qur’an as our only primary source, and it not only doesn’t speak of any such event, it condemns such actions in no uncertain terms (see above on POWs and Pharaoh). By the way, we now think the chapter of the Table (5) is perhaps the last chapter of the Qur’an, and it says Muslims can share communal meals with Jews and Christians and intermarry with them. It doesn’t speak as though Jews have been massacred!/

Forest_Moon_of_Earth

What early sources are most reliable? Do you take for granted the image painted by hadith and sira in constructing the course of Muhammad’s life?

Juan Cole:

Hi! The book is based primarily on early seventh-century texts, especially the Qur’an itself. I compare and contrast the latter primarily to the 8 accounts by `Urwa ibn al-Zubayr identified as very widely transmitted by Schoeler and Goerke. I don’t use the very late and in my view unreliable al-Waqidi and making sparing use of Ibn Hisham and Tabari, primarily for illustrative purposes. I also compare the Qur’anic historical passages to contemporary Greek and Persian accounts. So the bulk of the book sets the Qur’an in dialogue with early 7th century Roman and Sasanian texts rather than centering on the biographies written 760s through 900s./

couponuser9

How do you maintain that Muhammad was a “Prophet of Peace” with the issue of abrogation and Sura at-Tawba being the second to last Sura revealed, particularly related to 9:5 and 9:29?

Especially when you take into account numerous Sahih Bukhari and Sahih Muslim ahadith & tafsir most notably from Ibn Kathir reinforcing the idea of the pious nature of Jihad Taleb as prescribed in these very verses, which are supposed to be binding for all time? Not to mention the horror stories like that of the Banu Qurayza found in Sirat Rasul Allah where Muhammad had between 600-900 men beheaded simply for reaching puberty under suspicion they were guilty of “betrayal” in the Siege of Yathrib?

Not uniquely violent/evil by for his time? Sure (assuming Muhammad even existed and wasn’t just a pre-Islamic Syriac Christian title for Jesus). But “peaceful”? It seems like a “click-bait” title.

I imagine that these points are covered in your book, and in other comments you have said that you expect criticisms to be from revisionists (Muhammad = Jesus in Syriac) and traditionalists (lack of Sunnah). I’m interested what your feedback is if you have the time.

Juan Cole

My book is based almost entirely on the Qur’an and does not use hadith or much of the sira or biographical literature written in the Abbasid period, much less Kathir! You might as well quote Crusaders from the medieval period for the meaning of the New Testament! I don’t accept the later accounts of the massacre of Jews because there is nothing like that in the Qur’an and the only thing faintly resembling it comes in a verse condemning the way Pharaoh used to behave. The chapter of Repentance/ Tawba (9) in my view is mainly about the battle of Hunayn with militant pagan Bedouins who had gathered to forestall the rise of a new center of authority once Mecca accepted Muhammad in 630. If read as injunctions to defend Mecca at Hunayn from these tribes, which seem to have reneged on peace treaties with the Prophet, the verses aren’t bellicose. If you fight a defensive battle, you have to do the things these verses say. By the way, I think the word qatala in these verses means ‘fight,’ not ‘slay,’ since taking captives is urged in the same breath, and most translations are bad here./

JC

h/t

h/t

© 2026 All Rights Reserved

© 2026 All Rights Reserved