( The Times of Israel) – Could someone earn a commendation for deliberately breaking the holiest object ever created, one that was crafted and inscribed by God Himself?

According to a midrash [scripture interpretation], this is exactly what happened to Moses. In our weekly scripture reading, Exodus 30:11–34:35 [“Ki Tisa”], Moses shatters the tablets after witnessing the sin of the children of Israel worshiping the Golden Calf, which seems to be an act of anger. While the text doesn’t provide God’s reaction to the destruction, the midrash imagines God saying to Moses:

“יִישַׁר כֹּחֲךָ שֶׁשִּׁבַּרְתָּ” (“Yishar kochacha she-shibarta”).

“Well done for shattering them!”

(Talmud Shabbat 87a, and Rashi on Deuteronomy 34:12)

This is where the custom of saying “Yasher Koach” originates – a congratulatory phrase literally meaning “may your strength be firm” but more commonly translated as “well done!”

This raises a profound question: why would Moses receive such praise for destroying the tablets, which were not only divinely created but were also inscribed with God’s very words? What’s praiseworthy about shattering, without permission, arguably the holiest object in history?

Or, was it truly holy?

In his Torah commentary called Meshekh Chokhma (“The Flow of Wisdom”), the great scholar Rabbi Meir Simcha HaCohen of Dvinsk (Lithuania, 1843-1926) offers a profound explanation.

He suggests that Moses’ actions were necessary to teach the Israelites—and all of us—a crucial lesson about counterfeit holiness.

Rabbi Meir Simcha explains that at the heart of the Golden Calf sin was the Israelites’ misconception of holiness. They mistakenly believed that Moses himself was intrinsically holy and that his relationship with God was the foundation of their holiness. When Moses was absent, they felt compelled to create another source of holiness.

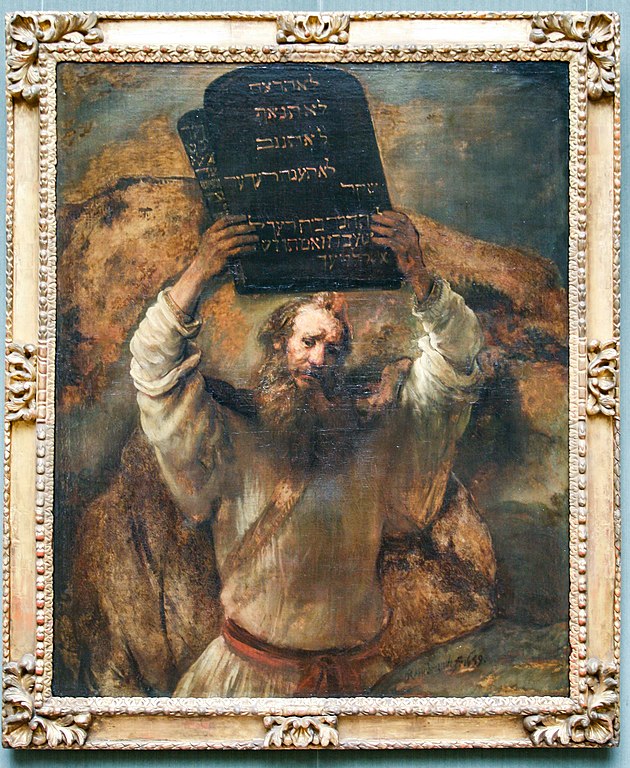

Rembrandt, “Moses smashing the Tablets of the Law,” 1659, Gemäldegalerie, Berlin. Public Domain. Wikimedia.

In response, Moses felt it necessary to correct this fundamental misconception. By shattering the tablets, he sent a powerful message: I am not holy in and of myself. I am just a man, like you. The Sanctuary, its vessels, and even the tablets are not inherently holy. Their sanctity is only derived from God’s presence among us. And God’s presence depends on our actions.

In essence, Moses demonstrated that if the people sin, these sacred objects lose their holiness. Even the Word of God itself, embodied in the tablets, loses its sanctity if the people’s relationship with God is corrupted. By deliberately shattering the tablets into smithereens, Moses made this truth visible to all.

Rabbi Meir Simcha extends this understanding to all aspects of life—people, places, and objects. Nothing in this world—outside of God—is intrinsically holy, not even the Land of Israel. Holiness is a status earned through just and moral behavior. It can be lost when people’s actions turn corrupt—when injustice, violence, and cruelty prevail.

As the Meshekh Chokhma [“The Flow of Wisdom”] writes poignantly:

There is no holiness in anything created in this world, only in the Creator, blessed be He. Do not imagine that the mountain [=Mount Sinai] is a holy thing and because of it the Lord appeared on it; as we see, the Israelites “when hearing the sound of the shofar, they will go up to the mountain,” as it is the dwelling place of animals and cattle. Only as long as the Divine Presence is upon the mountain, it is holy, because of the holiness of the Creator, blessed be His name. For it is not the land that honors man [=land does not make one holy], but man honors the land [=people—with their behavior— can make a land holy], and this is a noble idea.

In other words, the land becomes holy only when the people live according to God’s will as embodied in the moral commandments, fostering a society rooted in justice, equality, and compassion. To be fair, there are alternative, more mystical perspectives on the holiness of the land, such as those proposed by Rabbi Kook. However, Rabbi Meir Simcha emphatically rejects these views, emphasizing that all holiness, including that of the land, is conditional: If the people’s actions descend into oppression and injustice, the land loses its sanctity and becomes no different from any other land—merely a “dwelling place for animals and cattle.” To continue calling it holy regardless of the conduct of its inhabitants is the very definition of counterfeit holiness.

Reprinted from The Times of Israel with the author’s permission.

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved